WHITE PAPER

The Puntland Case, Federal Overreach, and the Terminal Crisis of the Somali State

Warsame Digital Media (WDM) White Paper — November 2025

Critical Analysis, Policy Briefing & Strategic Forecast

—

Executive Summary

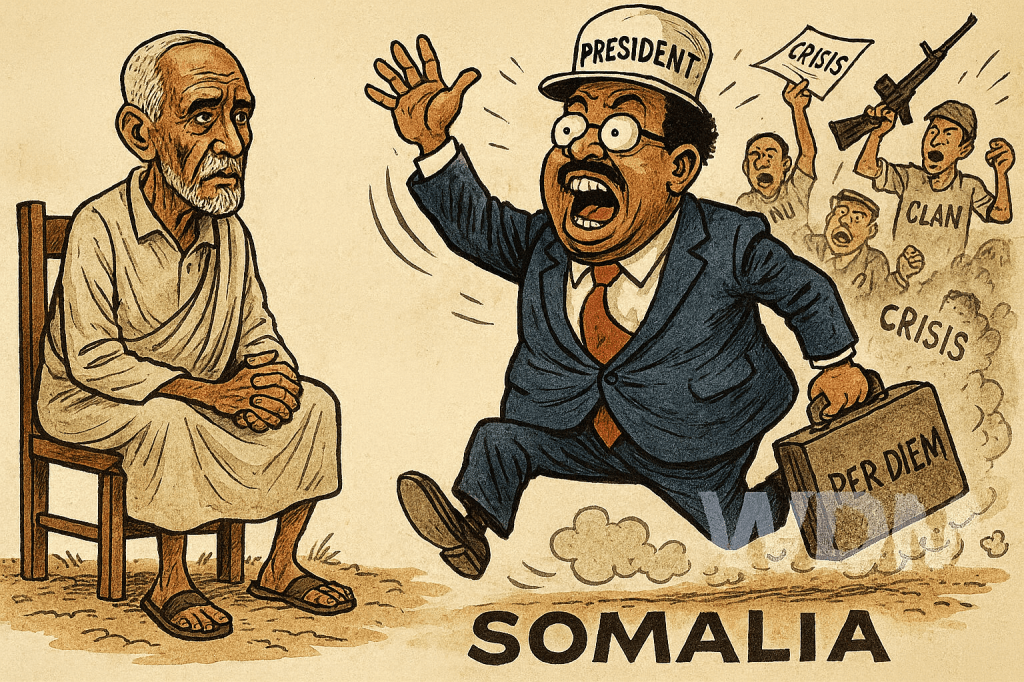

Somalia’s federal experiment—marketed in 2004 as the grand compromise to save a collapsed state—has now entered its terminal crisis stage. Federal–State relations have decayed into mutual suspicion, coercion, and political trench warfare. The epicenter of this long-running friction has always been Puntland, the founding architect and early defender of federalism.

Contrary to shallow narratives, the conflict did not begin with Said Abdullahi Deni, nor with the 2016 or 2022 political cycles. It was baked into the system from the start:

a flawed federal charter, a Mogadishu political class wedded to centralism, and national leadership incapable of honest reconciliation or constitutional fidelity.

Today, Somalia stands at a historic deadlock:

Most mandates expired or expiring;

NCC transformed from a coordination body into a coercive presidential whip;

Federalism reduced to a battlefield of grudges;

And a looming political vacuum inviting authoritarianism, fragmentation, and extremist exploitation.

This white paper dissects the historical roots, constitutional failures, federal overreach, Puntland’s defensive posture, the crisis of expired mandates, and presents actionable pathways forward.

1. Historical Roots of the Crisis

(2004–2025)

1.1 The Original Sin of Somali Federalism

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG), established in 2004 in Nairobi, was born under duress, foreign bargaining, and elite compromise. Key fractures appeared immediately:

Puntland demanded a negotiated federal design.

Mogadishu elites insisted on a centralized restoration of the unitary republic.

The TFG constitution was ambiguous by design—its drafters feared hard choices and left core powers undefined.

This ambiguity guaranteed decades of conflict.

1.2 Puntland’s Foundational Position

As co-architect of the 1998 Puntland Charter and federalism advocate since Abdullahi Yusuf’s era, Puntland insisted on:

Real power-sharing

Resource-sharing agreements

National reconciliation before state reconstruction

A civil service built on merit, not clan capture

These principles were ignored, sidelined, and later weaponized.

1.3 Mogadishu’s Post-2004 Centralist Mindset

Successive federal presidents—Abdullahi Yusuf excluded—saw federalism as:

A temporary inconvenience

A “necessary lie” to win international legitimacy

A project they would later reverse through political engineering

This included:

Manipulating parliamentary selections

Appointing “friendly” state leaders

Weaponizing security forces

And, eventually, repurposing the National Consultative Council (NCC) as an enforcement mechanism rather than a consultative forum.

2. The NCC:

From Dialogue Platform to Federal Weapon

2.1 Intended Purpose

The NCC was designed as a coordination venue for election planning, federal–state dialogue, and conflict resolution.

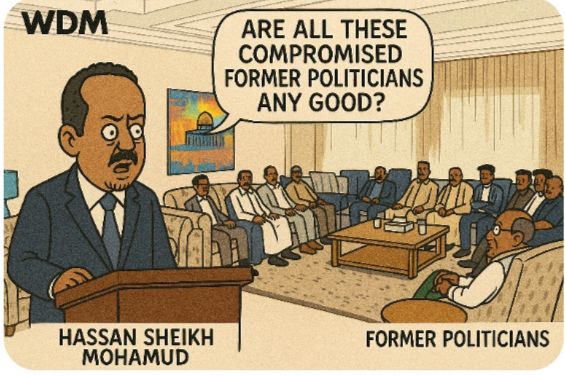

2.2 Actual Evolution

Under the regimes of Farmaajo and Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, the NCC became:

A forum to pressure Puntland and Jubaland

A mechanism to fabricate a façade of “consensus”

A tool to override federalism through “agreements” drafted in Mogadishu

A platform where federal leaders imposed decisions under donor pressure and security leverage

2.3 Break with Puntland and Jubaland

When NCC meetings shifted from negotiation to dictation, Puntland declared:

“The NCC cannot replace the Federal Constitution.”

This was the moment the system fractured beyond repair.

3. Structural Causes of Non-Collaboration

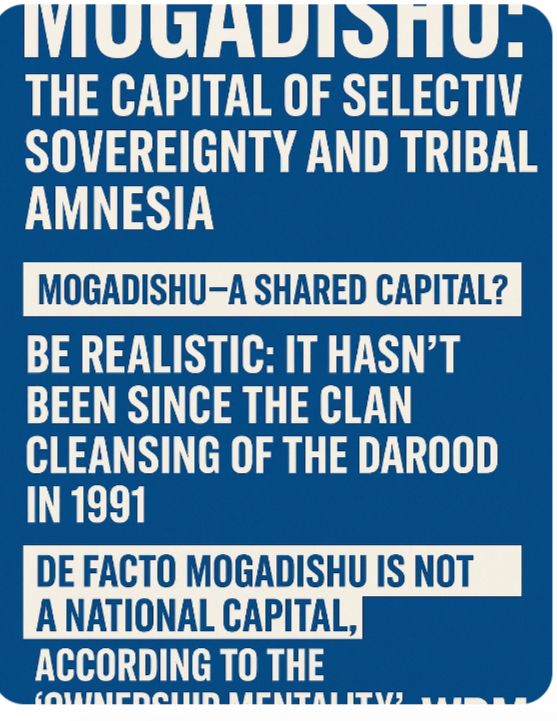

3.1 Constitutional Ambiguity

Key unresolved issues:

Natural resources

Fiscal federalism

Internal security powers

Boundaries of states

Status of the capital

Division of authority between federal and state institutions

With no constitutional court, no arbitration mechanism, and no political trust, Somalia’s federal architecture is held together with masking tape.

3.2 Federal Overreach

The central government has repeatedly imposed:

Hand-picked state presidents

Unilateral election models

Procurement and revenue centralization attempts

Security interference

Diplomatic representation monopoly

Manipulation of foreign aid distribution

3.3 Puntland’s Defensive Posture

Puntland’s political doctrine since 1998 remains consistent:

Federalism cannot exist without shared sovereignty

National institutions must be neutral, inclusive, and constitutional

Mogadishu cannot dictate political outcomes for regional states

No federal leadership can impose decisions through force or donor leverage

This doctrinal difference—not Deni’s personality—drives the conflict.

4. The Current Crisis (2023–2025)

4.1 Expired Mandates, Expired Legitimacy

Somalia is entering constitutional twilight:

Federal parliament: at or near expiration

Federal government: embroiled in extension maneuvers

State governments:

Southwest: expired

Hirshabelle: expired

Galmudug: expired

Jubaland: Extension (election) contested

Puntland: internal contest but functional

NCC: effectively suspended

Constitution: Unilaterally violated by the Federal Government, and permanently “provisional”

4.2 Deadlock and Governance Paralysis

This gridlock means:

No credible authority to lead national elections

No consensus on electoral model

No institution with country-wide legitimacy

A donor community fatigued and skeptical

A political class incapable of compromise

4.3 Risk Trajectory: Point of No Return

Somalia now faces:

Fragmentation into de facto confederal units

Parallel governments (Garowe vs Mogadishu model)

Security vacuums quickly filled by Al-Shabaab

Increased foreign meddling

Economic free-fall as budget support becomes conditional

A crisis of national identity and fate

5. Puntland as the Case Study:

Why the Friction is Structural—not Personal

5.1 Misdiagnosing the Conflict

Observers often blame:

Deni

Political competition

Election cycles

But the reality predates 2004.

5.2 Puntland’s Consistent Position Across Administrations

Puntland has maintained the same red lines across:

Abdullahi Yusuf

Mohamud Muse Hersi

Abdirahman Farole

Abdiweli Gaas

Said Abdullahi Deni

Different personalities.

One constitutional position.

5.3 Why Puntland is the Test Case

Because Puntland:

Was the first to formalize state administration (1998)

Hosts some of Somalia’s most stable districts

Produces a disproportionate share of technocrats

Acts as the bellwether for federal–state relations

If Mogadishu fails to partner with Puntland,

the entire federal project collapses.

6. Policy Recommendations

6.1 Constitutional Finalization with Guaranteed State Rights

Somalia must finalize the constitution with:

Resource sharing formulas

Fiscal federalism

Security powers

Clear division of authorities

A functioning Constitutional Court

Without a constitutional court, federalism is a political bar fight.

6.2 Rebuilding Trust through Genuine National Dialogue

A real National Reconciliation & Constitutional Conference (NRCC)—not NCC theatrics—is needed.

Held outside Mogadishu, with:

States

Civil society

Elders

Diaspora experts

Neutral facilitation

Guaranteed implementation mechanisms

6.3 Reforming the NCC (or Replacing It)

The NCC must be transformed from:

A presidential enforcement tool

Into:

A rules-based intergovernmental council with fixed mandates, rotating chairs, and consensus requirements.

6.4 Establishing an Independent Electoral Commission

To prevent every election cycle from becoming a coup attempt.

6.5 Mandate Synchronization

All FMS and the FGS must harmonize electoral calendars to avoid the current rolling crisis.

6.6 Create a Federal Arbitration Mechanism

A joint court or panel for resolving disputes between states and Mogadishu.

No more “winner takes all.”

7. Strategic Outlook: 2025–2030

If reforms fail, Somalia will enter a decade of:

Fragmentation

Parallel administrations

Regional interference (UAE, Qatar, Ethiopia, Turkey)

Fiscal collapse

Federalism abandoned in practice

Mogadishu reduced to a city-state with symbolic authority

If reforms succeed, Somalia could achieve:

Shared sovereignty

Predictable governance

Economic stabilization

Genuine federal democracy

National reconciliation after 30 years of conflict

—

Conclusion

Somalia’s federal crisis is not an accident. It is the predictable outcome of two competing visions of the Somali state, battling since 2004:

Centralists who dream of re-creating the pre-1991 dictatorship with a modern façade

Federalists who recognize that Somalia’s survival demands decentralization, compromise, and shared sovereignty

Puntland represents the federalist doctrine.

Mogadishu political elites remain welded to the centralist fantasy.

Unless Somalia confronts these contradictions—honestly, urgently, and transparently—the country is heading not toward a failed state, but a fragmented, irretrievable non-state.

Somali leadership must choose:

Federalism with integrity, or disintegration with inevitability.

—

© 2025 Warsame Digital Media (WDM)

Support fearless independent journalism that speaks truth to power.

Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081

You must be logged in to post a comment.