By Federico Battera, Saturday, August 12, 2000

UNDOS Research Specialist, Professor Development Studies – University of Trieste, Italy

Summary and purposes

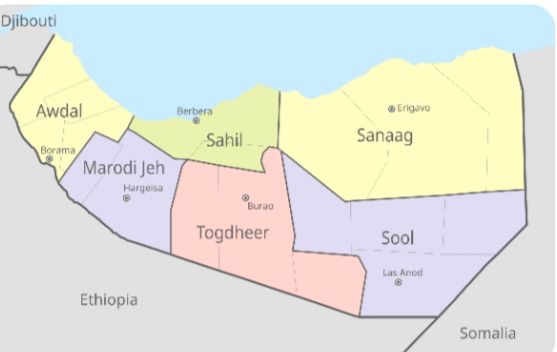

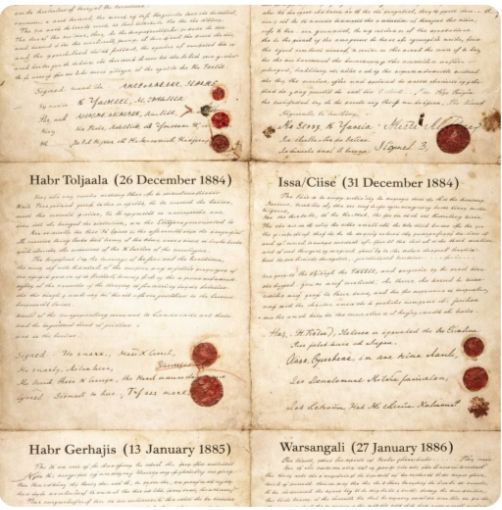

The crisis of the State in Africa goes back to the early 80s: postcolonial African state has been neither able ‘to rule’ economy, nor territorial policy. Ethnicity has spread all over the continent. However, after the failure of the consociative policies channeled through one-party systems, the most evident factor has been its territorial dimension. Since the middle of the 80s, as the State machine has been evidently unable to expand, politicization has taken over territory, giving ethnicity a new relevance as to contrast territorial legitimacy, which had been acquired by the State through the decolonization process.Somalia has not escaped the trend, sliding into a civil war since the beginning of the 80s. By early 90s it has become the paradigmatic example of the failure of the state. Centralization, as conceived by the collapsed regime, turned into a non-state existence, distinguished by independent areas controlled by different ‘fronts’ or ‘movements’ drawn up along clan lines. By mid 90s the situation improved in certain areas and stabilized in others. A de facto regionalization has gone out: since then, some areas has progressed to a ‘recovery’ condition, other has been classified by UN as ‘transition’ zones or ‘crisis’ zones, the latter characterized by a steadfast state of ravage and insecurity.The crisis of the State in Africa has generated in major cases conditions of democratic change. Constitutional processes has been the consequence of the change. Almost everywhere, it has been the output of a widely expressed need of strengthening democratic procedures. Only in few cases, the issue of territorial dimension of ethnicity has been addressed through strict federalist guidelines (as tried to do Ethiopia), but decentralization and devolution has remained the major question on the ground, together with democracy.’Recovery’ areas in Somalia (mainly Northwest and Northeast Somalia) around mid 90s gained momentum, as the situation in the rest of the country remained critical. Since then, new local conditions in the North have granted security and a certain stability, besides their differences. In 1991, the liberation struggle from Barre’s regime in Northwest Somalia ended with the declaration of independence of Somaliland. The constitutional process was the unavoidable following step. In 1993, a National transitional Charter were approved and accepted by all the communities in the region, giving full legitimization at the process. In 1997, a new (interim) Constitution were passed out, after a new Constitutional Conference that ended a two-years crisis. After that, Somaliland is waiting its international recognition.The constitutional process in Northeast Somalia has started later. As has been rightly stated by Farah, better conditions of peace and recovery do not necessarily lead to a climate favorable to a new institutional framework. Besides, Northeast Somalia did not share the same eagerness of Somaliland to acquire independence. Nevertheless, a constitutional process has started since the end of 1997. The aim of this paper is to outline the constitutional process and the main characteristics of the Charter approved and secondly to draw up the political effects of the new process on Somalia. After all, a new political entity has been originated from Somali disorder.As what concern the first point, the Charter, comparing to the Draft, stresses the Islamic identity of the new entity and its presidential biases. Regarding the political effects of the birth of the new regional state, it is personal opinion of the author that it will affect the entire reconciliation process in Somalia and, in a certain extent, the stability of Somaliland. Comparing to Somaliland, the territorial dimension of the new entity is openly averted. One reason is that a request for an international recognition is not on the agenda. However, an alternative explanation resides on the clan structure of the new state. Contrary to Somaliland, clan agreement has preceded any territorial definition. So far, Puntland has yet to be clearly defined on the map, a part the vague identification with Northeast Somalia. As we will see, important issues like that of decentralization of the state have not been avoided only with the intent of endorsing with more power the new political leadership (as trying to avoid the same fate of the country) but because of the naturally decentralized structure of Somali society. Seems like that the manifest ambiguities of the Charter has been provided in order to leave the door open for different future solutions. Indeed, the Charter is only provisional. Further alterations have not to be excluded, depending on internal and international conditions. As Somaliland, seven years later the first National Charter still in the middle of its constitutional process, Puntland might not easily finalized its one. The process, the participation degree and the informal institutional constraints that has been settled during the whole period more than its final document is the mirror of the vitality of the involved society. Focusing on it is not a vain academic exercise.The author had the opportunity to follow the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which with the assistance of foreign consultants drafted the Charter that was later submitted to the Constitutional Conference. Comparing the Draft with the final Charter has been the main source of the paper. Such a method elucidates the needs and the expectations of the members of the Constitutional Conference in charged with its approval. Such a source has been compared to local sources as well as previous reports.BackgroundFollowing the pattern of the Booroma National Charter, which formalized the birth of Somaliland during 1993, a new entity – the Puntland State of Somalia – was established in July 1998 out of a long Constitutional process that lasted more than two months. As in Boorama, the Constitutional Conference produced a three-year provisional Charter and elected a political leadership, i. e. a President and an Executive Council (called Council of Ministers in the Boorama Charter).Boorama paved the way, but it is a fact that the Puntland Constitutional Conference has been the product of a longer process, which officially started during 1997 but went back to the second National Reconciliation Conference of Addis Ababa of 1993. Indeed, during the National Reconciliation Conference, the SSDF (Somali Salvation Democratic Front) leadership anticipated its ‘federalist’ view of the future of Somalia, unofficially disclosed during 1994 in a statement by the Somali Community Information Centre in London. During the last five years, the federalist position has gradually acquired substance, recognizing the de facto situation on the ground: a clan-divided Somalia. Finally, the failure of several national reconciliation processes, from Sodere (1996) to Cairo (1997), created the condition for an autonomous regional process, pending the formation of other regional entities and the establishment of a new Federal Somalia.The Features of the CharterThe Charter, however transitory, defines a presidential system with a President able to dismiss the unicameral Parliament or House of Representatives (see Art. 12.5 of attached Charter). The House of Representatives consists of 69 members, representing of all constituent regions (Art. 8). However, an other chamber (of elders) has been proposed, called the Isimada (Art. 30) whose constitutional powers are not clear but would ostensibly need to be defined by the future Constitution.Even though, the Isimada could play a significant role, since the Charter formally recognizes to it a role of mediation between institutions (both State and regions and districts), in case of stalemate or disputes among “the community” (i. e. Puntland community as well a single clan) (see Art. 30.2): power that, together with that of selecting the members of the House of Representatives (30.3), gives it potentially an important role. The selection of the members has been carried out thanks to a careful balance between the numerical relevance of all communities and their number, to avert the exclusion of any political minority. Hence, this was an indirect election, without direct competition between parties and candidates. This required long debates among the communities involved; debates characterized by opposing vetoes between and among the communities followed by the selection of suitable candidates. Being the local community the natural constituency, it has been a consequence that only the elders played a role, as stated by the Charter itself (see, Art. 8.6).Although the selection seems to have relied on territorial criteria, it closely follows more an ‘a-territorial’ and consociative model. Such a criteria has already settled on the issue of the ministerial posts as well of the departments, agencies, judiciary agencies etc. So far, these are the de facto base of the forthcoming decentralization of the State (Art. 1.8), waiting for the matter to be regulated by law (Art. 18.1). Meanwhile, the State, and the Executive in particular, will nominate the governors of the regions and the mayors of districts, but always after direct consultation with district elders (Art. 18.3). The matter of decentralization is particularly delicate because one of the reasons for the collapse of Somalia was the unbalanced relation between the political center and periphery. In this sense, the Charter is still unclear and vague. What is evident is that the Charter does not recognize any formal function to the District Councils (DCs) and definitely removes any pre-exisiting regional community council (Art. 9.5).The matter shall be resolved in the future by the Executive.Besides the legislative one, the House of Representatives has other important responsabilities (see Art. 10.3): the approval and the rejection of ministerial nominees proposed by the President, the ratification or rejection of agreements and negotiations to achieve a federal national solution with other regional entities, and of all the future proposals submitted by the Executive concerning decentralization. Moreover, the Charter bestows the power to remove the immunity of the President on the House of Representatives (the so-called impeachment; Art. 14.1) upon a two-thirds majority vote. The procedure must be submitted to the House by the Executive-nominated (but House-approved) Attorney General.The Judiciary must be independent of both the Executive and the Legislative (Art. 19.1). Three levels of proceedings have been put in force (Primary Courts, Courts of Appeal and Supreme Court) (Art. 19.2), but the Charter recognizes, encourages and supports “alternative dispute resolution” (Art. 25.4) in keeping with the traditional culture of Puntland. Therefore, the State directly recognizes the force of the xeer (the customary law), that so far has held more sway than penal codes in the region.Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is the “basis” of law (Arts. 2 and 19.1). An implicit recognition of the superiority of ?ari‘a law exists, even though the lawmakers have preferred to avoid the more mandatory “the only source” of law, as in other juridical contexts. This is an ambiguous formula aiming to both recognize the ongoing regional process of re-Islamization as well as defuse its excessive aspects. Therefore, the Charter continually emphasizes the values of Islam, the State religion (Art. 2). The President himself must be a practicing Muslim (Art. 12.3), a quality not required for the members of the House (Art. 9). The Constitutional Court, which shall come into force with the future Constitution, is entrusted with all the issues and conflicts that might arise between Islamic jurisprudence and the law of the State and the Constitution itself (Art. 21.5). This conformity to Islamic values and the general reference of the Charter to the Islamic identity of Puntland is, moreover, stressed by the good relations that, pending the creation of Federal Somalia, Puntland is willing to maintain with the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) (Art. 5.3), which the original Draft did not mention.The general stress on the Islamic identity is confirmed in the chapter on the fundamental rights and freedom (Art. 6). On this point, the Charter introduces the widest changes in respect to the Draft. The Charter recognizes the freedom of thought and conscience, but forbids any religious propaganda other than Islam (Art. 6.2). This was one of the more discussed issues, during the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which introduced the Draft to the Conference. In its approved version, the Draft made no reference to such a prohibition. In Article 6.2.1, the Draft explicitly recognized other religious denominations without the limitations introduced later by the Charter, which prefers to consider other creeds as “freedom of thought and conscience“. So clarified, the prohibition of other religious propaganda is not intended to limit a fundamental right of thought, which is per se unlimitable. It is a fact, that almost all the future Puntland citizens are, practicing or not, Muslims. Such statements are probably intended to define more precisely the religious identity of the State, especially in respect to the outside Islamic world, in particular after allegations that Ethiopia stand behind the constitutional process had been spread in the country.Contrary to the Draft, the Charter necessitates the adoption of regulation of freedom of expression. Article 6.3 contains the prohibition of torture unless the person is sentenced by courts in accordance with Islamic law. This is an indirect admission of the legality of corporal punishments. Such punishment is admitted by Islamic law (as hudud) but not by Somali customary law (xeer). Defining this punishment as “torture” contradicts the new State’s (not the Charter) acceptance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Art. 5.2). This evident contradiction has been obviously only a problem of lack of understanding between different linguistic versions. The Draft, originally written in English, strongly forbids torture (Art. 6.3) and any other degrading treatment – “no one shall be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…“. The English version of the approved Charter cuts the sentence relating to the degrading treatment, introducing a misleading distinction between torture and Islamic (corporal) punishments – “no one shall be subjected to torture unless sentenced by the Islamic Courts“. This distinction is more evident in the Somali version of the Charter, with the word jir-dil (lit. “body-beaten”) replacing “torture” openly referring to corporal punishments.It is worth noticing that the Charter explicitly introduces a specific citizenship (Art. 1.11), regulated by law, but recognizing from now on the right of every Somali citizen, who respects the Charter and the law, to reside in Puntland and conduct any economic activity (Art. 1.5). The issue of citizenship was intentionally avoided by the Draft which preferred formulas as “the people of Puntland will accept only those limitations on their sovereignty that may arise from their obligations as citizens of a democratic Federal Somalia” (Art. 1.5 of the Draft)”. Moreover, the Charter, at the Article 1.9, cut the word “Democratic” from that of the Draft, preferring to label Somalia simply “Federal” (Art. 1.9). This thought-provoking omission (almost all present constitutional systems define themselves as ‘democratic’) probably should be understood as the product of the strong will to adhere to a re-established Somalia only at particular conditions leaving open other options, but saving the federal formula. In other words the present Charter is intended to give precise limitations to those who should participate in the name of Puntland in a constitutional process at the national level, affecting the agenda of future reconciliation processes.As far as this delicate point of the cession of sovereignty is concerned, the Draft introduced as Annex 1 (Powers and Functions that Puntland is willing to transfer to or share with the Federal Government of a democratic Federal Somalia) a fine distinction between transferable functions and shareable functions. The former is defined as functions exclusively belonging to the Federal Government, (mainly, the regulation of currency and Foreign affairs), and the latter as those belonging to the states, (the regulation of the seas and the airspace of Somalia, national defense, the determination of customs fees and the management of the Federal Bank). Of all these regulations remains scant in the final Charter apart from a reference in Article 1.6. This article leaves, in a very vague way, to the dialogue between states or between Puntland state and the Central government, after the approval of the House of Representatives (Art. 10.3), what will be transferred to the future Central Federal Government. Hence, Puntland is part of Somalia, and it is striving to recreate the unity of Somali people (Art. 1.4), but the modalities of realization remain only an option still to be negotiated. So far, in fact, Puntland has not advanced any international recognition.The effects of the birth of Puntland on the process of reconciliation and fragmentation in SomaliaAt a first glance, the Charter outlines the structure of the government as the Draft does, but more unbalanced to the presidency. First, the President has the power to dismiss the House of Representatives (Art. 12.5, h), a power the Draft did not grant. Second, the State of Emergency (Art. 12.5, l), limited by the Draft to six months, is totally unlimited in the Charter. The choice of the name of the chief of the Executive itself (President) instead of Chief Minister, as proposed in the Draft, comes from the need to ensure a stronger Executive, as was so clear during the long discussions within the Preparatory Committee. Most likely, the Preparatory Committee intended to reserve this title for the Federal Executive. Therefore, the House has no way to dismiss the Executive – but the same occurred in the Draft – except for the impeachment (requiring upon a two-thirds majority) and the rejection of other ministerial nominees (Art. 10.3, d).The Constitutional Conference itself empowered the President for a three-year transitional period. Cabdullahi Yuusuf, a prominent military and political leader of the now dissolved SSDF, was elected with more than 80% of the votes (377) cast out of the 469 members of the Community Constitutional Conference. This gives him a free hand for his three-year term of office, as is the case for other Arab and African presidential systems. Nevertheless, without any formal strong check and balance, the Executive does face an “informal” balance in the strong political autonomy of the traditional leaderships (isimo). Indeed, the Charter recognizes their crucial mediation functions (Arts. 30, 8 and 18); among the most important of them is the role of selecting the representatives. Differently from the Guurti of Somaliland, in this case the Isimo have preferred to renounce more defined roles that would have restricted their exercise of authority, preferring to maintain an uninstitutionalized ‘gray zone’ where they could intervene without any defined restriction and with much more flexibility in order to achieve a more widespread political consensus. It remains to be seen whether those recognized powers will remain in place in the more complex and complete Constitution to come, at the end of the transitional process.This unceasing search for the widest political consensus over issues and this concern about unanimity, manifested during the Constitutional Conference (which went far beyond the scheduled fifteen days) show how a political tradition both resists and adapts itself to modern politics. Freedom of association, including the right to form political parties, however admitted (Art. 6.2, b), is de facto bypassed by a non-party system, where different positions over issues are channeled through clan networks and interest groups (economic, regional, religious and family groups). That does not mean that opposition and disputes are definitively overcome, but that these are rather voiced through interest groups.The formation of Puntland itself is the result of an intercommunity agreement between all Harti (Majeerteen + Dhulbahante + Warsangeli) communities of the North. Is a matter of concern that this agreement should start a border conflict with the neighboring countries or the others de facto entities. Indeed, the Article 1. of the Charter establishes the borders along the former regions and districts which comprise a Harti majority: Bari, Nugaal, Sool, southern Togdheer (Buuhoodle district), Mudug (with the exception of Hobyo and Xarardheere districts) and Southern, Eastern and North-Eastern Sanaag. So defined, the Puntland State of Somalia claims sovereignty over territories that constitute part of Somaliland (Sanaag, Sool and Togdheer).That these regions and districts constitute parts of Somaliland may be matter of future conflicts between the two states. The communities of these districts did not completely take part in the first constituent congress (shir beeleed) of 1991 in Burco which declared independence, but did participate in the 1993 congress in Boorama which drew up the first Charter of Somaliland. Moreover, Somaliland, since the 1991 declaration, is in search of an international recognition relying on the legal basis of its previous short independence (only five days) before it merged with the former Italian Trusteeship Territory of Somalia in 1960.The creation of Puntland State of Somalia has, indeed, created a stalemate between the two entities. Fortunately, it has not so far deteriorated to a military conflict, maybe thanks to the Ethiopian political mediation between the two. The geographical proximity and the economic dependence on Ethiopia, together with the open hostility of Egypt and the Arab League towards the independence process in Somaliland lead to unalignment of the political position of Somaliland to that of Ethiopia.At the present, the government of Somaliland is, indeed, unable to exert a direct rule over its eastern part, which has largely joined Puntland. Maxmuud Fagadheh, a Dhulbahante from Eastern Somaliland, Foreign Affairs minister of the Cigaal government, is still in the government of Somaliland. In the meantime, 213 delegates out of the 469 to be present at the Constitutional Conference of Puntland came from Eastern Somaliland. Sool and Sanaag sent 27 of the 69 representatives to the Parliament of Puntland. Maxamed Cabdi Xaashi, the former leader of dismissed USP, the leading political and military faction in Eastern Somaliland, has been elected to the Vice-Presidency of Puntland, and three of the nine cabinet ministers of Puntland come from the contested regions. Moreover, an official statement of Harti traditional leaders (Isimo) of Eastern Somaliland associated themselves with the process of formation of Puntland and, so doing, legitimized this process, although the Isimo themselves are fully entitled to be part of the Guurti (the Senate of elders of Somaliland). In other words, Eastern Somaliland might become a buffer zone between the two entities, without clearly defined sovereignty.One of the first effects of the formation of Puntland might be that Somaliland government gives up its claim of independence. In this perspective, the recent declaration of President Cigaal in favor of a confederation system for a united Somalia, after his February journey in Egypt makes sense. A more long-term effect should be the proliferation of other new regional entities as the product of intercommunity (interclan) agreements. Besides, Puntland itself, as it appears today, could be easily named Hartiland. The Charter itself, in Article 1.2, leaves the door open to further additions to Puntland State, first of all “The community that participated in the Garowe consultancy meeting on February 1998“, the meeting which started the final phase of the constitutional process. This is a clear reference to the Marreexaan of Northern Galgaduud, which withdrew in the last stages of the process. Their further participation could transform Puntland from a Northern Hartiland to a Northern Daaroodland.In this perspective, Somalia should take the form on the ground, which was outlined by the SSDF network document in London 1994: a Federal Somalia founded on five entities corresponding to the five large clan confederations – Dir (Isaaq + Ciise + Gadabuursi) in the northwest, Northern Daarood in the north-east, Hawiye in the middle, Digil and Mirifle in the interiverine area (Bakool e Baay), Southern Daarood in the TransJuba area. A similar process is, indeed, restarting in the interiverine area after the push out of SNA from Baaydhaba by the RRA, with the support of Ethiopian troops. On the contrary, one in Hiiraan, the other in TransJuba had different experiences. In Hiiraan the process started in May 1998. It was led by five ex USC (United Somali Congress)-SNA factions (representing five different Hawiye clans of the region), after their successful ‘secession’ from Caydiid’s movement. This process is still incomplete because it tried to embrace the whole Hawiye clan family. A similar process in the TransJuba region has never started because of the internal conflict between factions, among different Daarood movements and the guri/galti (indigenous/newcomers) conflict. Finally, it was definitively halted by the recent seizure of Kismaayo by the combined forces of SNA and SNF.Among the main hindrances in the spreading of the pattern of regional reconstruction processes are: the pursuit of a centralist and anti-federalist approach by the joint administration of Mogadishu, and in particular by the SNA-Caydiid faction, and the anti-clan and unitary approach of the militant wing of the Islamist movement, based mainly in the Upper Juba region (Gedo) (but now threatened by the Ethiopian army), but with a strong political presence in both Banaadir and Mogadishu. These two factors are, in a certain way, bound together, even if the Islamist movement seems to have dropped its ‘taliban’ strategy of military conquest, after its failures at Boosaaso in 1992 and in the Ogaadeen between 1996 and 1997. This movement now prefer to affect local administrations through its social and juridical programs.Concluding remarks and options for the futureBoth northern regions, Somaliland and Puntland, were largely spared the civil conflict following the dramatic collapse of Barre regime. This fact gives them an undeniable asset in respect to the southern regions for a true implementation of reconciliation process. Even if they have not been completely free of clan strife, the northern regions still preserve strong societal ties. The institutional recognition of the role played by the traditional leadership in Puntland in the seven-year period of peaceful self-government in a stateless situation, has come only at the end of this process. However, the mediation role of the elders has not been so successful in other regions of Somalia for several reasons. Generally speaking, outside the Majeerteen context, Somali society lacks a stable hierarchy of paramount chiefs, and it follows that mediation can achieve only a local dimension. Nevertheless, in the northwestern regions (Somaliland) a regionalist feeling has widely spread in the last thirty years. In this part of Somalia, after the collapse of the State, the elders have collectively expressed this feeling better than the SNM, frequently paralyzed by leadership competition. Such regional affinities may be reached in the interiverine region, which has developed similar regionalist feelings after years of ravaging war and exploitation by the former regime, even if the civil conflict has left room for a confrontation between groups. Similar results are more hard to find in the Shabelle and Juba regions because of the confused societal situation complicated by the civil war and migrations.What is going on in Somalia from a political and constitutional point of view represents a defiance of the territorial principle and roots of international law. There is no doubt that international law is still playing and will play an important role in affecting the future juridical and constitutional framework of local governments, but what we are seeing throughout Somalia (and in other part of Africa) is a re-appropriation of imported institutional formulas by local political (and juridical) tradition. This involved the issue of the transplant of western institutions and their encounter with the so-called ‘informal’ sector, which as a concept has been by now enlarged to embrace not only the economic but the political and juridical dimensions. This issue is beyond the purpose of this paper, but has deep influence on contemporary Somalia.From a territorial point of view, the birth of Puntland not only reopens the whole question of internal borders in Somalia but also weakens the meaning of internal and external borders. They remain (in accordance with international law) and even produce a schizophrenic proliferation of district and sub-district boundaries defining community homelands but, in the meantime, generating the search for alternative and ‘informal’ solutions. This is one of the reasons for the failure or the incomplete success of the formal district governments and the better performances of the more flexible and aterritorial institutions such the guurti and isimo.From this point of view, the problem of sovereignty between Somaliland and Puntland that arises from the participation of Sool and Sanaag in the latter’s constitutional process is simply eluded by the participation of Harti in the parliamentary process and in the government of Somaliland. A similar process is smoothly developing between Puntland and the Somali region of Ethiopia: though not widely known, some Ethiopian Harti representatives sit in the Puntland House of Representatives.Similar problems between regional entities may arise and similar solutions may be found when other regional processes reach a more advanced stage. Hence, the formation of new entities will not necessarily mean conflict, but contested territories should play in the future a buffer role. The local concept of State sovereignty does not naturally match with the rigid concept of State territory. Instead, it should expand in the ‘official’ territory of other countries in a flexible way and wherever members of its community are found. This is exactly one of the options offered to end the conflict and to reconstruct Somalia by the LSE consultant to the European Union during 1995. Today, is effectively put into effect in all Somali regions without respect of internal and external borders. From another point of view, it is a slide back to a legal status of the community group, confirmed by a citizenship which corresponds to kinship. These are new elements of extreme importance to those who are directly or indirectly committed to developing alternative solutions in the African context, split up between State sovereignty and ethnic allegiance. What is advancing in Somalia is a more flexible and a more restricted idea of what the State is and means in Africa (and elsewhere). |

You must be logged in to post a comment.