Once upon a time, Mogadishu produced the Union of Islamic Courts (UIC)—a legal innovation so “brilliant” it collapsed faster than a mud hut in the Gu rainy season. Like all great Somali experiments in governance, the UIC was born out of high ideals, khat-fueled debates, and an unshakable faith in recycling old warlords under new titles. Its unintended consequence? The birth of a rebellious teenager called Al-Shabab, who took the family name but never came back for family dinners.

Who is the Mother of Al-Shabab?

The question is not whether Al-Shabab came from the UIC womb—it is whether Mogadishu’s political class still pays child support. If UIC was the mother, then Damul-Jadid was surely the doting uncle, always sneaking the child candy and ideological bedtime stories. Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, then a middle-class academic entrepreneur turned militia sponsor, stood shoulder to shoulder with the Al-Shabab maternity ward, making sure the baby was born strong enough to one day terrorize the entire Somali state.

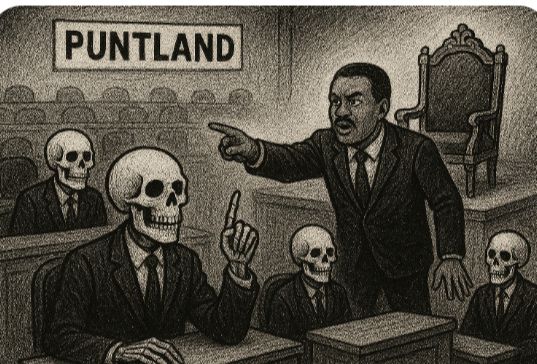

But let us not forget the SIMAD College Tragedy of 2006. Instead of graduation gowns, bright-eyed students were handed rusty rifles and packed into trucks for the Baydhaba front line—Somalia’s version of a compulsory internship. The Ethiopian army and the TFG gave them their performance evaluation in the form of heavy artillery, and like every unpaid intern, they were discarded and unaccounted for. The crime was never registered, and accountability was sent to the same graveyard as the missing students.

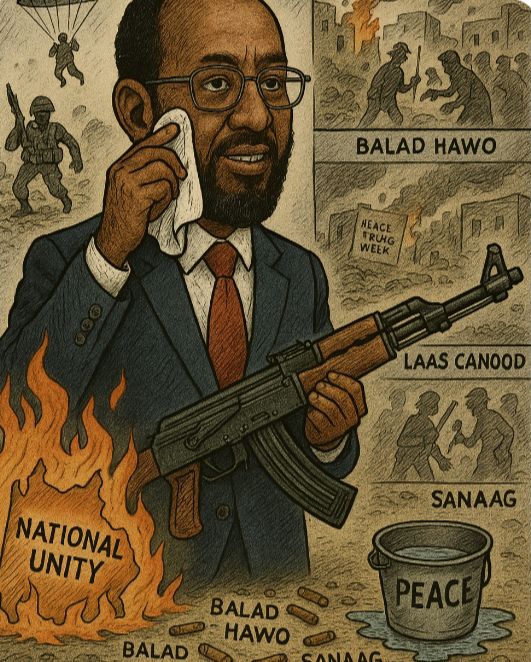

The President’s Amnesia

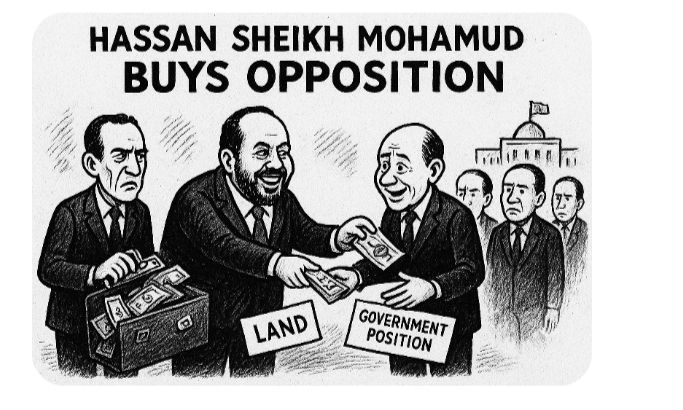

Fast forward to today, and President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud parades around Villa Somalia as if history began only after his second term swearing-in ceremony. He speaks of “fighting Al-Shabab” with a straight face, while skeptics whisper: “But weren’t you their classmate, neighbor, and at one point, tactical ally?” The irony is thicker than Mogadishu dust: the very man who once outsourced young blood to Al-Shabab’s apprenticeship program now claims to be Somalia’s top anti-terrorist general.

The President’s speeches against Al-Shabab are like a father publicly condemning truancy while secretly buying his delinquent son new sneakers. Everyone claps politely, but the street remembers who funded the bus rides to Baydhaba. Until Hassan Sheikh produces receipts for those lost SIMAD students, his anti-terror campaign remains less about eradicating Al-Shabab and more about editing Wikipedia pages.

A Country That Forgets Too Easily

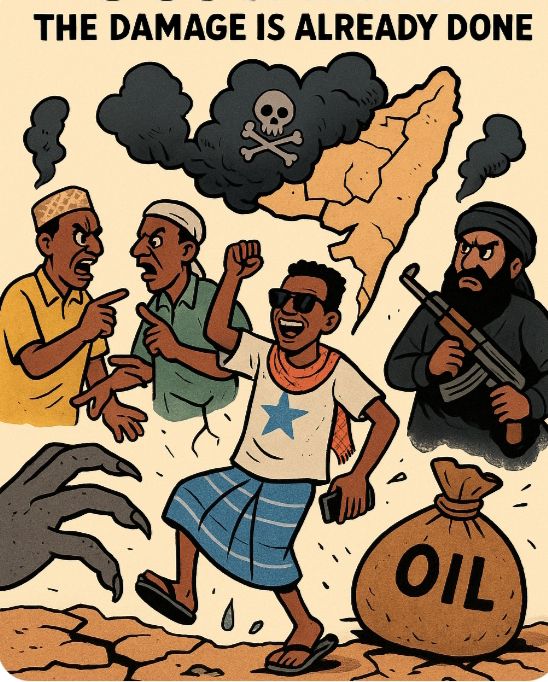

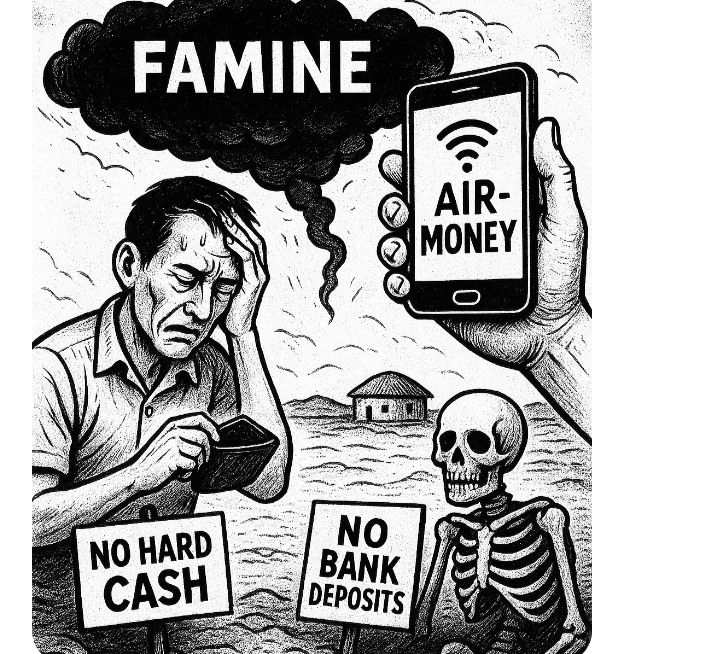

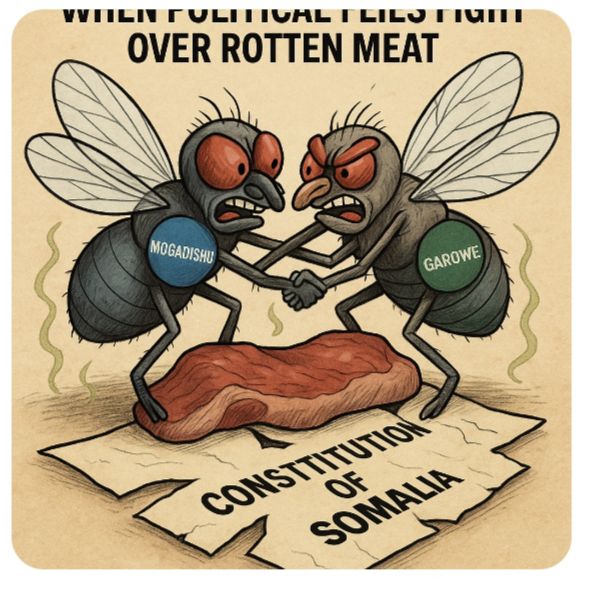

Somalia’s tragedy is not merely Al-Shabab’s existence, but the collective amnesia that allows perpetrators to rebrand as saviors. Warlords become ministers, extremists become reformists, and sponsors of student militias become “His Excellency.” Meanwhile, the bodies of the unaccounted still echo in the silence of Baydhaba fields.

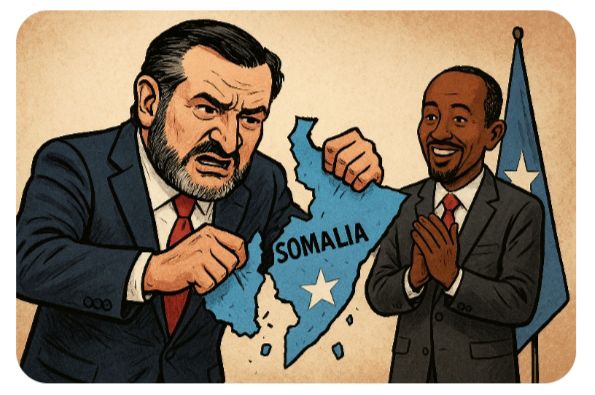

Perhaps the biggest unintended consequence of the UIC was not just Al-Shabab, but also the normalization of Somali political recycling. Yesterday’s rebel is today’s president, today’s president is tomorrow’s exile, and tomorrow’s exile will return as a peace negotiator sponsored by the UN. And the cycle spins on—slicker than a khat dealer’s tongue.

The Burden of Proof

Until President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud can answer for the Baydhaba students, until he can acknowledge Damul-Jadid’s role in Al-Shabab’s teenage years, and until Mogadishu stops pretending history began last week, every anti-terror campaign out of Villa Somalia will remain suspect.

As for the rest of us, we are left to watch this tragicomedy unfold—another episode in Somalia’s long-running soap opera: “UIC: The Mother That Ate Her Children.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.