| Source: SOMALIA WATCH |

| By Federico Battera, Saturday, August 12, 2000 UNDOS Research Specialist, Professor Development Studies – University of Trieste, Italy Summary and purposes The crisis of the State in Africa goes back to the early 80s: postcolonial African state has been neither able ‘to rule’ economy, nor territorial policy. Ethnicity has spread all over the continent. However, after the failure of the consociative policies channeled through one-party systems, the most evident factor has been its territorial dimension. Since the middle of the 80s, as the State machine has been evidently unable to expand, politicization has taken over territory, giving ethnicity a new relevance as to contrast territorial legitimacy, which had been acquired by the State through the decolonization process.Somalia has not escaped the trend, sliding into a civil war since the beginning of the 80s. By early 90s it has become the paradigmatic example of the failure of the state. Centralization, as conceived by the collapsed regime, turned into a non-state existence, distinguished by independent areas controlled by different ‘fronts’ or ‘movements’ drawn up along clan lines. By mid 90s the situation improved in certain areas and stabilized in others. A de facto regionalization has gone out: since then, some areas has progressed to a ‘recovery’ condition, other has been classified by UN as ‘transition’ zones or ‘crisis’ zones, the latter characterized by a steadfast state of ravage and insecurity.The crisis of the State in Africa has generated in major cases conditions of democratic change. Constitutional processes has been the consequence of the change. Almost everywhere, it has been the output of a widely expressed need of strengthening democratic procedures. Only in few cases, the issue of territorial dimension of ethnicity has been addressed through strict federalist guidelines (as tried to do Ethiopia), but decentralization and devolution has remained the major question on the ground, together with democracy.’Recovery’ areas in Somalia (mainly Northwest and Northeast Somalia) around mid 90s gained momentum, as the situation in the rest of the country remained critical. Since then, new local conditions in the North have granted security and a certain stability, besides their differences. In 1991, the liberation struggle from Barre’s regime in Northwest Somalia ended with the declaration of independence of Somaliland. The constitutional process was the unavoidable following step. In 1993, a National transitional Charter were approved and accepted by all the communities in the region, giving full legitimization at the process. In 1997, a new (interim) Constitution were passed out, after a new Constitutional Conference that ended a two-years crisis. After that, Somaliland is waiting its international recognition.The constitutional process in Northeast Somalia has started later. As has been rightly stated by Farah, better conditions of peace and recovery do not necessarily lead to a climate favorable to a new institutional framework. Besides, Northeast Somalia did not share the same eagerness of Somaliland to acquire independence. Nevertheless, a constitutional process has started since the end of 1997. The aim of this paper is to outline the constitutional process and the main characteristics of the Charter approved and secondly to draw up the political effects of the new process on Somalia. After all, a new political entity has been originated from Somali disorder.As what concern the first point, the Charter, comparing to the Draft, stresses the Islamic identity of the new entity and its presidential biases. Regarding the political effects of the birth of the new regional state, it is personal opinion of the author that it will affect the entire reconciliation process in Somalia and, in a certain extent, the stability of Somaliland. Comparing to Somaliland, the territorial dimension of the new entity is openly averted. One reason is that a request for an international recognition is not on the agenda. However, an alternative explanation resides on the clan structure of the new state. Contrary to Somaliland, clan agreement has preceded any territorial definition. So far, Puntland has yet to be clearly defined on the map, a part the vague identification with Northeast Somalia. As we will see, important issues like that of decentralization of the state have not been avoided only with the intent of endorsing with more power the new political leadership (as trying to avoid the same fate of the country) but because of the naturally decentralized structure of Somali society. Seems like that the manifest ambiguities of the Charter has been provided in order to leave the door open for different future solutions. Indeed, the Charter is only provisional. Further alterations have not to be excluded, depending on internal and international conditions. As Somaliland, seven years later the first National Charter still in the middle of its constitutional process, Puntland might not easily finalized its one. The process, the participation degree and the informal institutional constraints that has been settled during the whole period more than its final document is the mirror of the vitality of the involved society. Focusing on it is not a vain academic exercise.The author had the opportunity to follow the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which with the assistance of foreign consultants drafted the Charter that was later submitted to the Constitutional Conference. Comparing the Draft with the final Charter has been the main source of the paper. Such a method elucidates the needs and the expectations of the members of the Constitutional Conference in charged with its approval. Such a source has been compared to local sources as well as previous reports.BackgroundFollowing the pattern of the Booroma National Charter, which formalized the birth of Somaliland during 1993, a new entity – the Puntland State of Somalia – was established in July 1998 out of a long Constitutional process that lasted more than two months. As in Boorama, the Constitutional Conference produced a three-year provisional Charter and elected a political leadership, i. e. a President and an Executive Council (called Council of Ministers in the Boorama Charter).Boorama paved the way, but it is a fact that the Puntland Constitutional Conference has been the product of a longer process, which officially started during 1997 but went back to the second National Reconciliation Conference of Addis Ababa of 1993. Indeed, during the National Reconciliation Conference, the SSDF (Somali Salvation Democratic Front) leadership anticipated its ‘federalist’ view of the future of Somalia, unofficially disclosed during 1994 in a statement by the Somali Community Information Centre in London. During the last five years, the federalist position has gradually acquired substance, recognizing the de facto situation on the ground: a clan-divided Somalia. Finally, the failure of several national reconciliation processes, from Sodere (1996) to Cairo (1997), created the condition for an autonomous regional process, pending the formation of other regional entities and the establishment of a new Federal Somalia.The Features of the CharterThe Charter, however transitory, defines a presidential system with a President able to dismiss the unicameral Parliament or House of Representatives (see Art. 12.5 of attached Charter). The House of Representatives consists of 69 members, representing of all constituent regions (Art. 8). However, an other chamber (of elders) has been proposed, called the Isimada (Art. 30) whose constitutional powers are not clear but would ostensibly need to be defined by the future Constitution.Even though, the Isimada could play a significant role, since the Charter formally recognizes to it a role of mediation between institutions (both State and regions and districts), in case of stalemate or disputes among “the community” (i. e. Puntland community as well a single clan) (see Art. 30.2): power that, together with that of selecting the members of the House of Representatives (30.3), gives it potentially an important role. The selection of the members has been carried out thanks to a careful balance between the numerical relevance of all communities and their number, to avert the exclusion of any political minority. Hence, this was an indirect election, without direct competition between parties and candidates. This required long debates among the communities involved; debates characterized by opposing vetoes between and among the communities followed by the selection of suitable candidates. Being the local community the natural constituency, it has been a consequence that only the elders played a role, as stated by the Charter itself (see, Art. 8.6).Although the selection seems to have relied on territorial criteria, it closely follows more an ‘a-territorial’ and consociative model. Such a criteria has already settled on the issue of the ministerial posts as well of the departments, agencies, judiciary agencies etc. So far, these are the de facto base of the forthcoming decentralization of the State (Art. 1.8), waiting for the matter to be regulated by law (Art. 18.1). Meanwhile, the State, and the Executive in particular, will nominate the governors of the regions and the mayors of districts, but always after direct consultation with district elders (Art. 18.3). The matter of decentralization is particularly delicate because one of the reasons for the collapse of Somalia was the unbalanced relation between the political center and periphery. In this sense, the Charter is still unclear and vague. What is evident is that the Charter does not recognize any formal function to the District Councils (DCs) and definitely removes any pre-exisiting regional community council (Art. 9.5).The matter shall be resolved in the future by the Executive.Besides the legislative one, the House of Representatives has other important responsabilities (see Art. 10.3): the approval and the rejection of ministerial nominees proposed by the President, the ratification or rejection of agreements and negotiations to achieve a federal national solution with other regional entities, and of all the future proposals submitted by the Executive concerning decentralization. Moreover, the Charter bestows the power to remove the immunity of the President on the House of Representatives (the so-called impeachment; Art. 14.1) upon a two-thirds majority vote. The procedure must be submitted to the House by the Executive-nominated (but House-approved) Attorney General.The Judiciary must be independent of both the Executive and the Legislative (Art. 19.1). Three levels of proceedings have been put in force (Primary Courts, Courts of Appeal and Supreme Court) (Art. 19.2), but the Charter recognizes, encourages and supports “alternative dispute resolution” (Art. 25.4) in keeping with the traditional culture of Puntland. Therefore, the State directly recognizes the force of the xeer (the customary law), that so far has held more sway than penal codes in the region.Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is the “basis” of law (Arts. 2 and 19.1). An implicit recognition of the superiority of ?ari‘a law exists, even though the lawmakers have preferred to avoid the more mandatory “the only source” of law, as in other juridical contexts. This is an ambiguous formula aiming to both recognize the ongoing regional process of re-Islamization as well as defuse its excessive aspects. Therefore, the Charter continually emphasizes the values of Islam, the State religion (Art. 2). The President himself must be a practicing Muslim (Art. 12.3), a quality not required for the members of the House (Art. 9). The Constitutional Court, which shall come into force with the future Constitution, is entrusted with all the issues and conflicts that might arise between Islamic jurisprudence and the law of the State and the Constitution itself (Art. 21.5). This conformity to Islamic values and the general reference of the Charter to the Islamic identity of Puntland is, moreover, stressed by the good relations that, pending the creation of Federal Somalia, Puntland is willing to maintain with the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) (Art. 5.3), which the original Draft did not mention.The general stress on the Islamic identity is confirmed in the chapter on the fundamental rights and freedom (Art. 6). On this point, the Charter introduces the widest changes in respect to the Draft. The Charter recognizes the freedom of thought and conscience, but forbids any religious propaganda other than Islam (Art. 6.2). This was one of the more discussed issues, during the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which introduced the Draft to the Conference. In its approved version, the Draft made no reference to such a prohibition. In Article 6.2.1, the Draft explicitly recognized other religious denominations without the limitations introduced later by the Charter, which prefers to consider other creeds as “freedom of thought and conscience“. So clarified, the prohibition of other religious propaganda is not intended to limit a fundamental right of thought, which is per se unlimitable. It is a fact, that almost all the future Puntland citizens are, practicing or not, Muslims. Such statements are probably intended to define more precisely the religious identity of the State, especially in respect to the outside Islamic world, in particular after allegations that Ethiopia stand behind the constitutional process had been spread in the country.Contrary to the Draft, the Charter necessitates the adoption of regulation of freedom of expression. Article 6.3 contains the prohibition of torture unless the person is sentenced by courts in accordance with Islamic law. This is an indirect admission of the legality of corporal punishments. Such punishment is admitted by Islamic law (as hudud) but not by Somali customary law (xeer). Defining this punishment as “torture” contradicts the new State’s (not the Charter) acceptance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Art. 5.2). This evident contradiction has been obviously only a problem of lack of understanding between different linguistic versions. The Draft, originally written in English, strongly forbids torture (Art. 6.3) and any other degrading treatment – “no one shall be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…“. The English version of the approved Charter cuts the sentence relating to the degrading treatment, introducing a misleading distinction between torture and Islamic (corporal) punishments – “no one shall be subjected to torture unless sentenced by the Islamic Courts“. This distinction is more evident in the Somali version of the Charter, with the word jir-dil (lit. “body-beaten”) replacing “torture” openly referring to corporal punishments.It is worth noticing that the Charter explicitly introduces a specific citizenship (Art. 1.11), regulated by law, but recognizing from now on the right of every Somali citizen, who respects the Charter and the law, to reside in Puntland and conduct any economic activity (Art. 1.5). The issue of citizenship was intentionally avoided by the Draft which preferred formulas as “the people of Puntland will accept only those limitations on their sovereignty that may arise from their obligations as citizens of a democratic Federal Somalia” (Art. 1.5 of the Draft)”. Moreover, the Charter, at the Article 1.9, cut the word “Democratic” from that of the Draft, preferring to label Somalia simply “Federal” (Art. 1.9). This thought-provoking omission (almost all present constitutional systems define themselves as ‘democratic’) probably should be understood as the product of the strong will to adhere to a re-established Somalia only at particular conditions leaving open other options, but saving the federal formula. In other words the present Charter is intended to give precise limitations to those who should participate in the name of Puntland in a constitutional process at the national level, affecting the agenda of future reconciliation processes.As far as this delicate point of the cession of sovereignty is concerned, the Draft introduced as Annex 1 (Powers and Functions that Puntland is willing to transfer to or share with the Federal Government of a democratic Federal Somalia) a fine distinction between transferable functions and shareable functions. The former is defined as functions exclusively belonging to the Federal Government, (mainly, the regulation of currency and Foreign affairs), and the latter as those belonging to the states, (the regulation of the seas and the airspace of Somalia, national defense, the determination of customs fees and the management of the Federal Bank). Of all these regulations remains scant in the final Charter apart from a reference in Article 1.6. This article leaves, in a very vague way, to the dialogue between states or between Puntland state and the Central government, after the approval of the House of Representatives (Art. 10.3), what will be transferred to the future Central Federal Government. Hence, Puntland is part of Somalia, and it is striving to recreate the unity of Somali people (Art. 1.4), but the modalities of realization remain only an option still to be negotiated. So far, in fact, Puntland has not advanced any international recognition.The effects of the birth of Puntland on the process of reconciliation and fragmentation in SomaliaAt a first glance, the Charter outlines the structure of the government as the Draft does, but more unbalanced to the presidency. First, the President has the power to dismiss the House of Representatives (Art. 12.5, h), a power the Draft did not grant. Second, the State of Emergency (Art. 12.5, l), limited by the Draft to six months, is totally unlimited in the Charter. The choice of the name of the chief of the Executive itself (President) instead of Chief Minister, as proposed in the Draft, comes from the need to ensure a stronger Executive, as was so clear during the long discussions within the Preparatory Committee. Most likely, the Preparatory Committee intended to reserve this title for the Federal Executive. Therefore, the House has no way to dismiss the Executive – but the same occurred in the Draft – except for the impeachment (requiring upon a two-thirds majority) and the rejection of other ministerial nominees (Art. 10.3, d).The Constitutional Conference itself empowered the President for a three-year transitional period. Cabdullahi Yuusuf, a prominent military and political leader of the now dissolved SSDF, was elected with more than 80% of the votes (377) cast out of the 469 members of the Community Constitutional Conference. This gives him a free hand for his three-year term of office, as is the case for other Arab and African presidential systems. Nevertheless, without any formal strong check and balance, the Executive does face an “informal” balance in the strong political autonomy of the traditional leaderships (isimo). Indeed, the Charter recognizes their crucial mediation functions (Arts. 30, 8 and 18); among the most important of them is the role of selecting the representatives. Differently from the Guurti of Somaliland, in this case the Isimo have preferred to renounce more defined roles that would have restricted their exercise of authority, preferring to maintain an uninstitutionalized ‘gray zone’ where they could intervene without any defined restriction and with much more flexibility in order to achieve a more widespread political consensus. It remains to be seen whether those recognized powers will remain in place in the more complex and complete Constitution to come, at the end of the transitional process.This unceasing search for the widest political consensus over issues and this concern about unanimity, manifested during the Constitutional Conference (which went far beyond the scheduled fifteen days) show how a political tradition both resists and adapts itself to modern politics. Freedom of association, including the right to form political parties, however admitted (Art. 6.2, b), is de facto bypassed by a non-party system, where different positions over issues are channeled through clan networks and interest groups (economic, regional, religious and family groups). That does not mean that opposition and disputes are definitively overcome, but that these are rather voiced through interest groups.The formation of Puntland itself is the result of an intercommunity agreement between all Harti (Majeerteen + Dhulbahante + Warsangeli) communities of the North. Is a matter of concern that this agreement should start a border conflict with the neighboring countries or the others de facto entities. Indeed, the Article 1. of the Charter establishes the borders along the former regions and districts which comprise a Harti majority: Bari, Nugaal, Sool, southern Togdheer (Buuhoodle district), Mudug (with the exception of Hobyo and Xarardheere districts) and Southern, Eastern and North-Eastern Sanaag. So defined, the Puntland State of Somalia claims sovereignty over territories that constitute part of Somaliland (Sanaag, Sool and Togdheer).That these regions and districts constitute parts of Somaliland may be matter of future conflicts between the two states. The communities of these districts did not completely take part in the first constituent congress (shir beeleed) of 1991 in Burco which declared independence, but did participate in the 1993 congress in Boorama which drew up the first Charter of Somaliland. Moreover, Somaliland, since the 1991 declaration, is in search of an international recognition relying on the legal basis of its previous short independence (only five days) before it merged with the former Italian Trusteeship Territory of Somalia in 1960.The creation of Puntland State of Somalia has, indeed, created a stalemate between the two entities. Fortunately, it has not so far deteriorated to a military conflict, maybe thanks to the Ethiopian political mediation between the two. The geographical proximity and the economic dependence on Ethiopia, together with the open hostility of Egypt and the Arab League towards the independence process in Somaliland lead to unalignment of the political position of Somaliland to that of Ethiopia.At the present, the government of Somaliland is, indeed, unable to exert a direct rule over its eastern part, which has largely joined Puntland. Maxmuud Fagadheh, a Dhulbahante from Eastern Somaliland, Foreign Affairs minister of the Cigaal government, is still in the government of Somaliland. In the meantime, 213 delegates out of the 469 to be present at the Constitutional Conference of Puntland came from Eastern Somaliland. Sool and Sanaag sent 27 of the 69 representatives to the Parliament of Puntland. Maxamed Cabdi Xaashi, the former leader of dismissed USP, the leading political and military faction in Eastern Somaliland, has been elected to the Vice-Presidency of Puntland, and three of the nine cabinet ministers of Puntland come from the contested regions. Moreover, an official statement of Harti traditional leaders (Isimo) of Eastern Somaliland associated themselves with the process of formation of Puntland and, so doing, legitimized this process, although the Isimo themselves are fully entitled to be part of the Guurti (the Senate of elders of Somaliland). In other words, Eastern Somaliland might become a buffer zone between the two entities, without clearly defined sovereignty.One of the first effects of the formation of Puntland might be that Somaliland government gives up its claim of independence. In this perspective, the recent declaration of President Cigaal in favor of a confederation system for a united Somalia, after his February journey in Egypt makes sense. A more long-term effect should be the proliferation of other new regional entities as the product of intercommunity (interclan) agreements. Besides, Puntland itself, as it appears today, could be easily named Hartiland. The Charter itself, in Article 1.2, leaves the door open to further additions to Puntland State, first of all “The community that participated in the Garowe consultancy meeting on February 1998“, the meeting which started the final phase of the constitutional process. This is a clear reference to the Marreexaan of Northern Galgaduud, which withdrew in the last stages of the process. Their further participation could transform Puntland from a Northern Hartiland to a Northern Daaroodland.In this perspective, Somalia should take the form on the ground, which was outlined by the SSDF network document in London 1994: a Federal Somalia founded on five entities corresponding to the five large clan confederations – Dir (Isaaq + Ciise + Gadabuursi) in the northwest, Northern Daarood in the north-east, Hawiye in the middle, Digil and Mirifle in the interiverine area (Bakool e Baay), Southern Daarood in the TransJuba area. A similar process is, indeed, restarting in the interiverine area after the push out of SNA from Baaydhaba by the RRA, with the support of Ethiopian troops. On the contrary, one in Hiiraan, the other in TransJuba had different experiences. In Hiiraan the process started in May 1998. It was led by five ex USC (United Somali Congress)-SNA factions (representing five different Hawiye clans of the region), after their successful ‘secession’ from Caydiid’s movement. This process is still incomplete because it tried to embrace the whole Hawiye clan family. A similar process in the TransJuba region has never started because of the internal conflict between factions, among different Daarood movements and the guri/galti (indigenous/newcomers) conflict. Finally, it was definitively halted by the recent seizure of Kismaayo by the combined forces of SNA and SNF.Among the main hindrances in the spreading of the pattern of regional reconstruction processes are: the pursuit of a centralist and anti-federalist approach by the joint administration of Mogadishu, and in particular by the SNA-Caydiid faction, and the anti-clan and unitary approach of the militant wing of the Islamist movement, based mainly in the Upper Juba region (Gedo) (but now threatened by the Ethiopian army), but with a strong political presence in both Banaadir and Mogadishu. These two factors are, in a certain way, bound together, even if the Islamist movement seems to have dropped its ‘taliban’ strategy of military conquest, after its failures at Boosaaso in 1992 and in the Ogaadeen between 1996 and 1997. This movement now prefer to affect local administrations through its social and juridical programs.Concluding remarks and options for the futureBoth northern regions, Somaliland and Puntland, were largely spared the civil conflict following the dramatic collapse of Barre regime. This fact gives them an undeniable asset in respect to the southern regions for a true implementation of reconciliation process. Even if they have not been completely free of clan strife, the northern regions still preserve strong societal ties. The institutional recognition of the role played by the traditional leadership in Puntland in the seven-year period of peaceful self-government in a stateless situation, has come only at the end of this process. However, the mediation role of the elders has not been so successful in other regions of Somalia for several reasons. Generally speaking, outside the Majeerteen context, Somali society lacks a stable hierarchy of paramount chiefs, and it follows that mediation can achieve only a local dimension. Nevertheless, in the northwestern regions (Somaliland) a regionalist feeling has widely spread in the last thirty years. In this part of Somalia, after the collapse of the State, the elders have collectively expressed this feeling better than the SNM, frequently paralyzed by leadership competition. Such regional affinities may be reached in the interiverine region, which has developed similar regionalist feelings after years of ravaging war and exploitation by the former regime, even if the civil conflict has left room for a confrontation between groups. Similar results are more hard to find in the Shabelle and Juba regions because of the confused societal situation complicated by the civil war and migrations.What is going on in Somalia from a political and constitutional point of view represents a defiance of the territorial principle and roots of international law. There is no doubt that international law is still playing and will play an important role in affecting the future juridical and constitutional framework of local governments, but what we are seeing throughout Somalia (and in other part of Africa) is a re-appropriation of imported institutional formulas by local political (and juridical) tradition. This involved the issue of the transplant of western institutions and their encounter with the so-called ‘informal’ sector, which as a concept has been by now enlarged to embrace not only the economic but the political and juridical dimensions. This issue is beyond the purpose of this paper, but has deep influence on contemporary Somalia.From a territorial point of view, the birth of Puntland not only reopens the whole question of internal borders in Somalia but also weakens the meaning of internal and external borders. They remain (in accordance with international law) and even produce a schizophrenic proliferation of district and sub-district boundaries defining community homelands but, in the meantime, generating the search for alternative and ‘informal’ solutions. This is one of the reasons for the failure or the incomplete success of the formal district governments and the better performances of the more flexible and aterritorial institutions such the guurti and isimo.From this point of view, the problem of sovereignty between Somaliland and Puntland that arises from the participation of Sool and Sanaag in the latter’s constitutional process is simply eluded by the participation of Harti in the parliamentary process and in the government of Somaliland. A similar process is smoothly developing between Puntland and the Somali region of Ethiopia: though not widely known, some Ethiopian Harti representatives sit in the Puntland House of Representatives.Similar problems between regional entities may arise and similar solutions may be found when other regional processes reach a more advanced stage. Hence, the formation of new entities will not necessarily mean conflict, but contested territories should play in the future a buffer role. The local concept of State sovereignty does not naturally match with the rigid concept of State territory. Instead, it should expand in the ‘official’ territory of other countries in a flexible way and wherever members of its community are found. This is exactly one of the options offered to end the conflict and to reconstruct Somalia by the LSE consultant to the European Union during 1995. Today, is effectively put into effect in all Somali regions without respect of internal and external borders. From another point of view, it is a slide back to a legal status of the community group, confirmed by a citizenship which corresponds to kinship. These are new elements of extreme importance to those who are directly or indirectly committed to developing alternative solutions in the African context, split up between State sovereignty and ethnic allegiance. What is advancing in Somalia is a more flexible and a more restricted idea of what the State is and means in Africa (and elsewhere). |

Tag: history

Talking Truth to Power

Preface

When I first compiled these essays into Talking Truth to Power, my purpose was simple: to memorialize the turbulent years of Somalia’s recent political history through independent critical analysis. What was written then, as commentary in real time, now reads like a record of warnings unheeded.

In 2025, the issues raised in these pages remain painfully relevant. Somalia’s federal experiment continues to falter, sabotaged from within by federal leaders who exploit clan identities for short-term power rather than building national institutions. The federal system, instead of evolving into a mechanism for cooperation and shared sovereignty, has become a battlefield of mistrust. The consequences are visible in the hollowing of governance, the erosion of public trust, and the weaponization of constitutional ambiguity.

Foreign interference, which I described years ago as “so many spearmen fighting over an ostrich,” has only deepened. Turkey, Qatar, the UAE, Ethiopia, and Kenya remain active players in Somalia’s politics—each pursuing strategic interests while Somalia itself remains fractured and vulnerable. Their money, weapons, and proxies have fueled division, leaving ordinary Somalis disillusioned and displaced.

At the same time, the Somali people are quietly voting with their feet. Cairo, Istanbul, Nairobi, Dubai, Kampala, and beyond now host growing Somali diasporas who left because of inflation, insecurity, and a sense that home offers little hope. This silent exodus, often overlooked in political debates, may prove one of the most significant shifts of our era: the loss of human capital and the quiet resignation of citizens who have ceased to believe in their state.

The essays in this volume—whether about Puntland’s lack of strategic vision, Mogadishu’s capture by foreign agendas, or the failures of leaders to rise above clan politics—stand as both analysis and indictment. They remind us that Somalia’s crises were neither sudden nor inevitable. They were cultivated by choices, by negligence, and by an elite class unwilling to learn from past mistakes.

Yet, there is still a lesson in these pages for the future. The Somali people have always shown resilience. SSC-Khatumo’s reassertion of political agency, Puntland’s insistence on federal rights, and civil voices demanding accountability are signs that the struggle for self-determination is not over. If anything, these scattered sparks point to the possibility of renewal—if only leaders can place principle above power, and citizens above clan.

This 2025 preface is not a republication of the book. It is a reminder that the fight to “talk truth to power” remains unfinished. My hope is that readers—whether students, diplomats, policymakers, or Somali citizens at home and abroad—will engage these writings not only as history, but as a challenge to act differently in the years ahead.

— Ismail H. Warsame

Garowe / Nairobi / Toronto, 2025

Report on the Political Implications of SSC-Khatumo’s Alignment with President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s Administration

May 2025

Prepared by WDM

Executive Summary

This report examines the political and strategic implications of the recent alignment between SSC-Khatumo and President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s federal government. This development is analyzed in the broader context of Somalia’s federal dynamics, inter-regional relations, and the symbolic and practical ramifications of SSC-Khatumo’s emerging role within the federal framework. While the move has been seen as a symbolic victory for SSC-Khatumo, it also exposes the fragile nature of federalism in Somalia and the complex interplay between legitimacy, recognition, and political leverage.

1. Introduction

The emergence of SSC-Khatumo as a political administration in northern Somalia has altered the federal landscape. Following its military victory over Somaliland forces and the liberation of Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn (SSC) territories, SSC-Khatumo has moved swiftly to assert itself within Somalia’s federal structure. Its recent political alignment with President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s administration marks a turning point with both opportunities and significant complications

2. Background and Context

SSC-Khatumo was born out of years of political marginalization, inter-regional contestation, and grassroots mobilization. Its roots lie in community resistance against both allegedly Puntland’s neglect and Somaliland’s expansionist policies. With the defeat of Somaliland forces in 2023–2024 with the assistance of Puntland State, SSC-Khatumo declared itself an autonomous administration seeking formal integration into the Somali federal system.

Simultaneously, the federal government under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has faced increasing isolation from influential federal member states (FMSs) like Puntland and Jubaland. This has left Villa Somalia with a diminished political coalition and a pressing need for new allies.

3. Analysis of SSC-Khatumo’s Alignment

3.1. Symbolic Recognition

SSC-Khatumo’s entry into the political orbit of Villa Somalia carries symbolic weight. It is viewed as a validation of its self-declared authority and an acknowledgment of its role in safeguarding Somali unity. The comparison to the Banadir Administration—Mogadishu’s local government entity without full FMS status—underlines the initial limitations of this recognition but still marks a step up from complete exclusion.

3.2. Practical Benefits and Risks

While symbolic recognition is important, practical benefits remain elusive. SSC-Khatumo lacks clear federal member state status and thus does not enjoy the same constitutional protections or budgetary entitlements as recognized FMSs. Furthermore, its relationship with the central government may expose it to co-optation risks, potentially undermining its grassroots legitimacy.

3.3. Proxy Representation of Puntland and Jubaland

In the vacuum left by Puntland and Jubaland, SSC-Khatumo is being perceived—rhetorically or otherwise—as a substitute voice in national politics. This dynamic places an unfair burden on a nascent administration and could invite tension with more established FMSs, particularly if SSC-Khatumo is seen as an instrument of Villa Somalia’s centralization agenda.

4. Implications for Somali Federalism

4.1. Fragility of the Federal System

The Somali federal model remains underdeveloped, and the selective recognition of regional entities exacerbates tensions. SSC-Khatumo’s ambiguous status is indicative of a system that lacks standardized criteria for inclusion, recognition, and political representation.

4.2. Risks of Political Fragmentation

Without a coherent framework, the piecemeal integration of new administrations could fuel further fragmentation. SSC-Khatumo’s rapid inclusion, juxtaposed with the exclusion of existing FMSs from key national processes, could provoke institutional instability and heighten inter-regional rivalries.

5. Geopolitical and Strategic Considerations

SSC-Khatumo’s emergence also affects Somalia’s geopolitical positioning. It challenges Somaliland’s claims over disputed territories, potentially reshaping diplomatic narratives. Moreover, its alignment with Villa Somalia could be leveraged in regional and international engagements, particularly regarding aid, security cooperation, and constitutional reform.

However, the symbolic recognition of SSC-Khatumo by the Federal Government could intensify the territorial disputes between Puntland and Somaliland. It challenges existing claims, alters political alliances, and adds complexity to Somalia’s federal dynamics. Resolving these disputes will require careful negotiation and a commitment to inclusive dialogue among all stakeholders

6. Recommendations

For the Federal Government:

Clarify SSC-Khatumo’s status within the federal constitution.

Ensure equitable resource distribution and institutional support.

Avoid politicizing the administration’s alignment for short-term gains.

For SSC-Khatumo:

Maintain independence in local governance to retain grassroots legitimacy.

Engage Puntland and Jubaland to avoid regional alienation.

Advocate for formal federal recognition through legal and political channels.

For International Partners:

Support inclusive dialogue on federalism and territorial administration.

Encourage a consistent framework for regional recognition.

Monitor political developments to ensure alignment with peace and stability goals.

7. Conclusion

SSC-Khatumo’s integration into President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s political alliance is both a symbolic step forward and a cautionary tale of Somalia’s federal experiment. It reflects the persistent gaps in institutional design, legitimacy, and political inclusion. The next phase of Somali state-building must prioritize consistency, dialogue, and transparency to prevent further fragmentation and to harness the energies of emerging regional actors like SSC-Khatumo for national unity and development.

Eradicating Corrupt Leadership in Africa: The Path to Freedom and Prosperity

Introduction

Africa, a continent brimming with potential, grapples with a pervasive challenge: corrupt leadership. The legacies of Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso and contemporary figures like Ibrahim Traoré underscore the transformative power of ethical governance. While Sankara’s revolutionary policies in the 1980s prioritized anti-corruption and social justice, Traoré’s recent rise highlights ongoing aspirations for accountability. This essay advocates for dismantling systemic corruption through democratic means, emphasizing the role of informed electorates, institutional reforms, and civic mobilization to usher Africa toward lasting freedom and prosperity.

Legacy of Visionary Leadership

Thomas Sankara, often called “Africa’s Che Guevara,” demonstrated that integrity and political will can drive change. During his brief tenure, he slashed government salaries, redistributed land, and invested in education and healthcare. Similarly, Ibrahim Traoré’s rhetoric against foreign exploitation and corruption resonates with youth and activists. However, their ascendancy through non-democratic means reveals a critical tension: sustainable progress requires systemic change, not just charismatic leaders. Sankara’s assassination and Traoré’s contested legitimacy remind us that enduring reform demands institutional, not personal, solutions.

The Corrosive Impact of Corruption

Corrupt leadership stifles development by diverting resources from critical sectors like healthcare and infrastructure. According to the African Union, corruption costs the continent over $148 billion annually, perpetuating poverty and inequality. Entrenched elites manipulate electoral systems, entrenching patronage networks that undermine democracy. Citizens, disillusioned by empty promises, often succumb to apathy or protests, as seen in recent uprisings in Sudan and Zimbabwe. The cycle of corruption and repression traps nations in stagnation leading to state failure. Somalia is the shining example of this African illness, necessitating urgent action.

Democratic Solutions: Voting Out Corruption

- Free and Fair Elections: Strengthening electoral commissions and enforcing transparency in voting processes are vital. Countries like Ghana and Botswana have shown that credible elections, monitored by civil society and international observers, can ensure peaceful transitions.

- Informed Electorate: Civic education empowers citizens to demand accountability. Mobile technology and grassroots campaigns, such as Nigeria’s #NotTooYoungToRun movement, can engage youth and combat voter apathy.

- Institutional Reforms: Anti-corruption agencies must operate independently, with prosecutorial power. Rwanda’s digitization of public services reduced bureaucratic graft, proving that systemic checks work.

Civil Society and Media as Watchdogs

Vibrant civil society organizations and a free press are bulwarks against tyranny. Investigative journalists, like Kenya’s John-Allan Namu, expose graft, while movements like #EndSARS in Nigeria mobilize public dissent. Social media amplifies marginalized voices, though governments often retaliate with repression. International partnerships, such as the African Peer Review Mechanism, can bolster local efforts without undermining sovereignty.

Challenges and Risks

Electoral fraud, voter intimidation, and disinformation campaigns persist. In nations like DR Congo, leaders cling to power by stifling opposition. Moreover, military coups—though sometimes popular—risk cyclical instability, as seen in Mali and Burkina Faso. True change requires patience: rebuilding trust in democracy is a marathon, not a sprint.

Case Studies: Lessons from Success

Botswana’s sustained democracy and low corruption levels stem from strong institutions and civic pride. Mauritius, ranking first in Africa for democracy, combines economic openness with robust welfare programs. These examples prove that cultural shifts toward accountability are achievable through persistence.

Conclusion

Africa’s journey to prosperity hinges on rejecting corruption and embracing participatory governance. While figures like Sankara and Traoré symbolize the hunger for change, lasting solutions lie in empowering citizens, reforming institutions, and upholding democratic principles. By voting out corrupt leaders and demanding transparency, Africans can reclaim their future—transforming the continent’s potential into tangible progress. The road is arduous, but collective resolve can turn the tide, ensuring freedom and prosperity for generations to come.

Recurring Governance Failures in Somalia: A Cycle of Division and Instability

Introduction

Somalia’s political landscape has been marred by cyclical governance failures since the collapse of General Siad Barre’s military regime in 1991. Despite transitioning to a federal structure, successive governments, including President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s current administration, have repeated historical mistakes by sidelining national reconciliation and political inclusivity. This essay examines how these governance lapses—exacerbated by centralization, constitutional violations, and foreign interference—undermine Somalia’s fight against extremism and jeopardize its fragile state-building process.

Historical Context: Authoritarianism and Clan Fragmentation

The Barre regime (1969–1991) entrenched authoritarianism, suppressing dissent and manipulating clan divisions to maintain power. Its collapse plunged Somalia into civil war, fragmenting the nation along clan lines. Post-1991 efforts to restore stability, including the transitional governments of the 2000s, failed to address deep-seated grievances. The 2012 Provisional Federal Constitution (PFC) aimed to decentralize power through federalism but has been inconsistently implemented, perpetuating mistrust between Mogadishu and regional states.

The Recurring Failure of Reconciliation

A persistent flaw in Somali governance is the elite’s reluctance to prioritize national reconciliation. Power struggles among political actors, often rooted in clan loyalties, have taken precedence over inclusive dialogue. For instance, the 2017 electoral process, which marginalized opposition voices, and the violent aftermath of the 2021 delayed elections highlight this trend. Such exclusionary tactics mirror Barre’s playbook, fostering resentment and cyclical violence.

Mohamud’s Centralized Governance: “We Will Stop to Await Anybody”

President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s second term (2022–present) has intensified centralization. His dismissal of federal member states’ perspectives—exemplified by clashes with Puntland and Jubaland over resource management and security—reflects a top-down approach. By marginalizing opposition groups and regional leaders, Mohamud risks alienating critical stakeholders. His declaration, “We will stop to await anybody,” epitomizes this unilateralism, undermining the PFC’s federal principles and deepening intergovernmental rifts.

Security Implications: Fractured Unity Amidst Extremist Threats

Al-Shabab and ISIS remain potent threats, controlling swathes of territory and exploiting governance vacuums. Effective counterterrorism requires coordination between federal and state authorities, yet Mogadishu’s strained relations with regional governments have led to fragmented military efforts. For example, Jubaland’s resistance to federal interference in its local security operations and elections has weakened offensives against Al-Shabab. Meanwhile, Somalia’s reliance on the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS, now AUSSOM)) underscores the inadequacy of its nascent security forces, a vulnerability exacerbated by political disunity.

Constitutional Violations and Federalism Disputes

The PFC envisions a balance of power between Mogadishu and federal states, but its provisional status allows ambiguous interpretations. Recent controversies, such as the central government’s unilateral amendments to electoral laws and control over foreign aid, violate the PFC’s spirit of power-sharing. States like Puntland have responded by declaring autonomy, signaling a crisis of confidence in the federal project. These disputes hinder consensus on critical issues, including the constitution’s finalization and resource distribution.

Foreign Interference: Complicating Sovereignty

Somalia’s fragility has invited foreign actors to pursue competing interests. Ethiopia, Kenya, Turkey, and the UAE have invested in infrastructure, military bases, and political alliances, often exacerbating internal divisions. For instance, UAE support for certain regional leaders contrasts with Turkish backing of Mogadishu, creating parallel power centers. Such interference undermines national sovereignty and distracts from inclusive state-building.

Conclusion: Toward Inclusive Governance

Somalia’s path to stability demands breaking the cycle of exclusion. President Mohamud must prioritize dialogue with federal states and opposition groups, adhering to the PFC’s federal framework. International partners should condition support on inclusive processes rather than backing factions. Only through genuine reconciliation and shared governance can Somalia neutralize extremism, reduce foreign dependency, and achieve lasting peace. The alternative—a continuation of centralized, divisive politics—risks perpetuating the very crises that have plagued the nation for decades.

Final Reflection

Somalia’s governance challenges are a testament to the dangers of repeating past mistakes. Learning from history requires courage to embrace inclusivity, uphold the rule of law, and prioritize national unity over narrow interests. The stakes—a sovereign, stable Somalia—could not be higher.

White Paper: Exploring Asymmetrical Federalism and Confederalism in the Somali Context

Executive Summary

Somalia’s governance crisis demands innovative solutions. This paper evaluates asymmetrical federalism alongside a confederal system as potential pathways to address constitutional violations, federal-state discord, and security threats. While a confederal model prioritizes maximal decentralization, asymmetrical federalism offers a middle ground, granting tailored autonomy to regions like Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland while preserving a unified state. Both models present opportunities and risks, requiring careful calibration to Somalia’s complex realities.

1. Alternative Model: Asymmetrical Federalism

Definition:

Asymmetrical federalism allows for variable autonomy among member states, recognizing historical, cultural, or political differences. Unlike classical federalism (uniform powers) or confederalism (state supremacy), it enables negotiated, region-specific arrangements under a shared constitutional framework.

Examples:

- Canada: Quebec has distinct language and civil law privileges.

- Spain: Catalonia and the Basque Country enjoy fiscal and linguistic autonomy.

- India: Jammu and Kashmir (pre-2019) and Northeastern states had special status.

1.1 Key Features

- Flexible Power-Sharing: Core federal functions (defense, currency) remain centralized, while states negotiate additional powers (e.g., policing, resource management).

- Constitutional Recognition: Legally enshrined differences (e.g., Somaliland’s unique status).

- Equity Mechanisms: Redistributive policies to prevent disparities between stronger and weaker states.

2. Comparative Analysis: Federal vs. Confederal vs. Asymmetrical Federalism

| Aspect | Federal System | Confederal System | Asymmetrical Federalism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sovereignty | Shared | Retained by states | Shared, with variable autonomy |

| Power Distribution | Uniform regional powers | Fully decentralized | Tailored to state needs |

| Conflict Resolution | Constitutional courts | Consensus-based | Hybrid (courts + negotiation) |

| Security | Centralized command | State-led | Mixed (central oversight + local operations) |

3. Opportunities of Asymmetrical Federalism for Somalia

3.1 Addressing Somaliland’s Secessionist Ambitions

- Grant Somaliland constitutionally recognized autonomy (e.g., control over security, customs, and education) while retaining symbolic ties to Somalia (e.g., flag, international representation).

- Example: Greenland’s self-rule within Denmark.

3.2 Resolving FG-FMS Deadlocks

- Allow Puntland and Jubaland to negotiate enhanced powers (e.g., oil revenue sharing, local policing) without dismantling federal institutions.

3.3 Mitigating Fragmentation Risks

- Maintain a unified military and foreign policy to counter Al-Shabaab/ISIS, while permitting states to manage local security operations.

3.4 Electoral Flexibility

- Adopt region-specific electoral models (e.g., Somaliland’s hybrid clan-system elections) under federal oversight to break national deadlocks.

4. Challenges of Asymmetrical Federalism

4.1 Complexity in Governance

- Negotiating and managing diverse agreements risks bureaucratic inefficiency and legal contradictions.

4.2 Inter-State Resentment

- States with fewer privileges (e.g., Hirshabelle, Galmudug) may reject perceived inequities, fueling new conflicts.

4.3 Constitutional Legitimacy

- Requires broad consensus to amend the PFC, which Mogadishu and distrustful FMS may resist.

4.4 External Exploitation

- Adversaries like Al-Shabab could exploit governance disparities to destabilize weaker regions.

5. Recommendations

- Constitutional Convention:

- Draft a new charter recognizing asymmetrical autonomy for Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland, while ensuring baseline federal protections for all states.

- Tiered Security Framework:

- Centralize national defense and intelligence under the FG, while delegating counterterrorism operations to capable states (e.g., Puntland’s Darawish forces).

- Asymmetrical Resource-Sharing:

- Let resource-rich states retain a higher share of revenues (e.g., Jubaland’s ports) but mandate contributions to a national cohesion fund.

- Phased Implementation:

- Pilot asymmetrical agreements in Puntland and Somaliland with AU/UN mediation before nationwide rollout.

- Strengthen Federal Institutions:

- Build impartial mechanisms (e.g., intergovernmental councils, courts) to resolve asymmetrical disputes.

6. Conclusion

Neither confederalism nor asymmetrical federalism alone can resolve Somalia’s crises. However, asymmetrical federalism offers a pragmatic compromise: it acknowledges Somalia’s diversity without abandoning unity. To succeed, it must be paired with guarantees of equity, robust conflict-resolution systems, and international support. Conversely, a confederal system risks institutionalizing fragmentation but could appeal if distrust in Mogadishu becomes irreparable. Somalia’s leaders must weigh these models against the catastrophic costs of inaction.

Endorsed by Warsame Digital Media

Date: March 11, 2025

This white paper underscores the urgency of reimagining Somalia’s governance. Whether through confederalism or asymmetrical federalism, the goal remains: a stable, inclusive Somalia capable of defeating extremism and fulfilling its people’s aspirations.

White Paper: Shaping Somalia’s Narrative – A Call for Responsible and Balanced Media Engagement

By Warsame Digital Media (WDM)

Introduction

Warsame Digital Media (WDM) recognizes the pivotal role of writers, narrators, and commentators in shaping Somalia’s story. As voices of influence, your words inspire perceptions locally and globally. While Somalia faces challenges, it also thrives with resilience, innovation, and hope. This white paper urges a shift toward balanced narratives that honor progress and foster unity, steering clear of defeatism and cynicism.

The Role of Media in Somalia’s Journey

Media bridges local and diaspora communities, amplifying voices and framing realities. In post-conflict societies, narratives can either fuel despair or ignite hope. Somalia’s story is multifaceted—acknowledging struggles while celebrating triumphs is vital for collective morale and nation-building.

The Challenge: Defeatism and Its Impact

Persistent negativity in discourse risks normalizing despair, deterring investment, and stifling grassroots efforts. Cynicism erodes trust in institutions and communal bonds. While critique is necessary, unchecked pessimism undermines Somalia’s progress.

The Power of Balanced Narratives

- Inspiration Drives Action: Stories of resilience, like youth-led startups or cultural revitalization, motivate societal engagement.

- Unity Over Division: Highlighting shared triumphs fosters national pride.

- Global Perception: Balanced narratives attract diaspora reinvestment and international partnerships.

Guidelines for Responsible Communication

- Avoid Absolutist Language: Replace “everything is broken” with “challenges persist, but progress is evident in…”

- Balance Critique with Solutions: Pair analysis of issues with examples of local solutions (e.g., community-led education initiatives).

- Amplify Positivity: Showcase entrepreneurship, art, tech innovation, and peaceful dialogue.

- Mind Emotional Impact: Consider how words affect vulnerable audiences, especially youth.

- Constructive Criticism: Offer actionable feedback instead of venting frustration.

- Collaborate: Partner with platforms like WDM to share uplifting stories.

Call to Action: Be Architects of Hope

WDM invites you to reframe Somalia’s narrative:

- Write with Purpose: Your pen can heal, unite, and inspire.

- Celebrate Quiet Victories: From small businesses to peacebuilding, every story matters.

- Engage Diaspora Thoughtfully: Bridge physical distance with cultural pride and optimism.

Conclusion

Somalia’s story is unfolding through its people. By choosing hope over cynicism, you become stewards of its future. WDM pledges support through resources, training, and platforms to amplify responsible storytelling. Together, let’s craft a narrative worthy of Somalia’s resilience.

Contact WDM: [iwarsame@ismailwarsame.blog/https://ismailwarsame.blog/@ismailwarsame]

“A nation’s greatness lies in its storytellers.” – Somali Proverb.

Message to Writers

Dear Change-Makers,

Your words shape destinies. As Somalia rebuilds, we urge you to wield your influence with care. Balance honesty with hope, critique with compassion. Share stories that ignite pride and possibility. Join WDM in fostering a narrative that reflects Somalia’s strength. Together, we rise.

With resolve,

Warsame Digital Media

Book Review: “Confessions of a British Spy and British Enmity Against Islam”

By M. SIDDIK GUMUS

WDM Book Review: “Confessions of a British Spy and Enmity Against Islam“

Introduction

“Confessions of a British Spy and British Enmity Against Islam” presents a strategic manual allegedly authored by a British spy during the colonial era, outlining methods to exploit perceived weaknesses in Muslim societies and dismantle their sources of strength. The text is accompanied by rebuttals that defend Islamic principles and Ottoman achievements, reflecting a clash between colonial subterfuge and cultural resilience. This review examines the book’s claims, the counterarguments provided, and their historical and ideological contexts.

Summary of the Book’s Claims

The original text identifies 13 weak spots within Muslim societies:

- Internal Divisions: Sectarian (Sunni-Shia), political (ruler vs. people), and tribal conflicts.

- Ignorance and Illiteracy: Alleged widespread lack of education.

- Spiritual and Moral Decay: Neglect of knowledge and conscience.

- Otherworldly Focus: Disengagement from worldly progress.

- Tyrannical Rulers: Emperors depicted as oppressive.

6–13. Infrastructure and Governance Failures: Unsafe roads, poor public health, economic collapse, weak military, and environmental neglect.

The book then lists 23 power sources of Muslims, including unity under Islam, adherence to religious practices (prayer, jihad, charity), strong community bonds, and reverence for scholars and the Qur’an. To undermine these, it recommends fostering division, obstructing education, promoting asceticism, and manipulating rulers.

Rebuttals and Counterarguments

The rebuttals, likely from a defender of Ottoman and Islamic heritage, systematically refute the claims:

- Internal Unity: The Ottoman system prioritized scholars, as seen in Sultan Mahmud II’s refusal to execute Mawlana Khalid Baghdadi, stating, “Scholars would by no means be harmful to the State.”

- Education and Literacy: Ottoman villages had mosques and schools; even peasants were literate in faith and crafts.

- Balance of Worldly and Spiritual: Citing the Prophet’s hadith, “Work for the world as though you’ll never die, and for the Hereafter as if you’ll die tomorrow,” the rebuttal emphasizes Islam’s holistic ethos.

- Infrastructure and Governance: Ottoman roads were safe for pilgrims, hospitals like those that treated Napoleon existed, and cities like Delhi under Firuz Shah boasted advanced irrigation systems.

- Military Strength: Historical examples, such as Bayezid I’s victory at Nicopolis (1396), challenge the claim of weak armies.

The rebuttal also counters strategies to erode Muslim strengths, arguing that Islamic teachings inherently promote unity, education, and ethical governance, making external subversion difficult.

Analysis

The original text reflects colonial tactics of division and cultural erosion, exploiting perceived vulnerabilities. However, the rebuttal’s reliance on Ottoman achievements risks idealizing the past. For instance, while Ottoman infrastructure was advanced for its time, later decline is overlooked. Similarly, the defense of caliphs as just rulers contrasts with historical complexities of power struggles.

The spy’s advice to promote asceticism (e.g., via Ghazali’s Ihya Ulum al-Din) is astutely countered by distinguishing zuhd (detachment from materialism) from neglect of worldly duties. The rebuttal’s emphasis on Islamic balance—education, hygiene, and governance—highlights a nuanced understanding often absent in colonial narratives.

Conclusion

“Confessions of a British Spy and British Enmity Against Islam” offers a stark lens into colonial strategies to destabilize Muslim societies by amplifying divisions and undermining cultural pillars. The rebuttals, rooted in Ottoman history and Islamic theology, reveal a resilient identity that resisted such tactics through communal cohesion and institutional strength. While the text serves as a historical artifact of imperial manipulation, the counterarguments underscore the enduring relevance of unity and ethical governance in facing external challenges. This dialogue between subversion and resilience remains pertinent in contemporary discourses on cultural identity and colonialism.

Rating: ★★★★☆ (A compelling historical document with rich counterpoints, though requiring critical engagement with both perspectives.)

This review synthesizes the text’s dual narratives, contextualizing them within broader historical and ideological struggles, and invites reflection on the interplay between external domination and cultural preservation.

THE IDIOSYNCRACIES OF THE SOMALI MAN

Somalis are pseudo-Muslims and are almost pagan in behavior and ways of life. Murder, theft and acts of blasphemy are considered patches of honor. Public theft, abuses of entrusted position, revenge, and punishment of real or perceived opponents and rivals are fair games for both ordinary men and Somali public officials. It is only in Somalia where you hear the President of a Republic claiming that his kids have the right to take advantage of his position in acquiring undeserved government privileges and unearned wealth; government officials, including ministers, looting government coffers, on the top of misappropriating salaries of their employees in daylight with impunity, and remain a functioning official or minister in Cabinet. One can infer from this that the boss of that particular minister was doing the same and didn’t bother firing the corrupt subordinate. The list of similar behaviors goes down to the office messengers and cleaners.

“According to the Greeks, there are three types of people on earth:

- The idiots

- The tribesmen, and

- Citizens

When the Greek used the word idiot, they didn’t use it as a curse word. Idiots are the people who just don’t care, if they write an exam, they’d cheat, if they’re in government, they’d steal. An idiot just doesn’t care at all. If he eats bananas, he throws the peels anywhere instead of putting it in a trash.

According to the Greek, some some societies have more idiots than tribesmen and citizens.

The next set of people are tribesmen, these are the set of people that look at everything from the point of view of their tribe. These are people who believe in you only if you’re part of their tribe. It can really be terrible to have a tribesman as a leader, he would alienate the rest.

When the Greeks talk about it, it’s not just about ethnicity, they also consider religion as a tribe. A great deal of Africans are tribes men because they view everyone from the point of view of their tribes. They trust only their tribesmen.

The last group of people are citizens. These people like to do things the right way, they will respect traffic light rules even if no one is watching them, they drive within speed limit. They respect laws, in an exam, they won’t cheat, if they’re in government, they won’t steal. They are compassionate people, they give to others to promote their well-being.

Some countries have more citizens than tribesmen and idiots, others have so many.

A tribesman can become a citizen through orientation, and an idiot can become a citizen by training and constant enforcement of the law.

Things will fall apart if you elect an idiot or a tribesman to lead if he has not been reformed,” truly reflecting most of the Somali men.

Based on this description, the Somali man is an extreme combination of the characters of THE IDIOT AND TRIBESMAN. Can he be reformed, and whose duty is it to do?

WDM BREAKING NEWS

WDM EDITORIAL

Two days ago few men calling themselves the NCC gathered in a dark room in Mogadishu with the intention of hijacking the entire agenda of Somali Peace and National Reconciliation Process (SPNRP), wiping out shamelessly with the stroke of a pen any modest gains of the people of Somalia for the past three decades. Their targets for elimination were all federal framework, constitutional arrangements, institution-building and any modicum of transitional agreements to put out the fire of the civil war in order to reconstruct Somalia anew.

For this moment in time, Somali people are now suddenly realizing that this portion of NCC men were almost all either active participants in the civil war as militiamen and insurgents themselves, or they were assistants and students of militia and extremist commanders. Suddenly, this realization becomes surreal and unfathomable.

In trying to turn the clock back in Somalia to the old days of mayhem and state failure intentionally or unintentionally, these men have discarded all norms of this fledgling Federal Government and its Federal Member States. Ironically, these men want to bury their dirty deeds and disservice in a rubber-stamp parliament approval with corruption, cronyism and under-hand manipulations. Would it work for them this time once again? Stay tuned.

Postscript: If there is any silver lining in their ugly prouncements, it is the statement that Somalis must go to the election polls, an an impossible task to implement in most of the regions they claim to govern. This is the result of psychological and political impact that recent earth-shattering Puntland State Council Elections might have on them.

ON SOMALIA’S HISTORY

ON PUNTLAND HISTORY

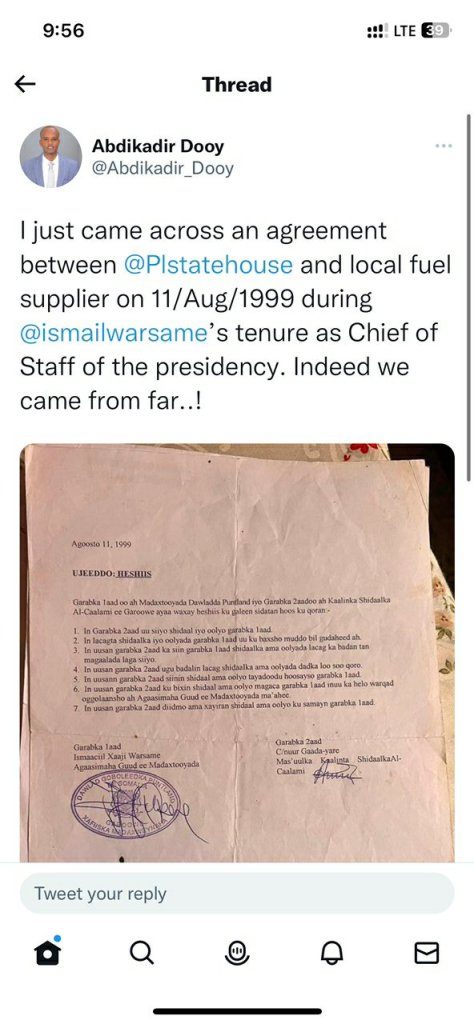

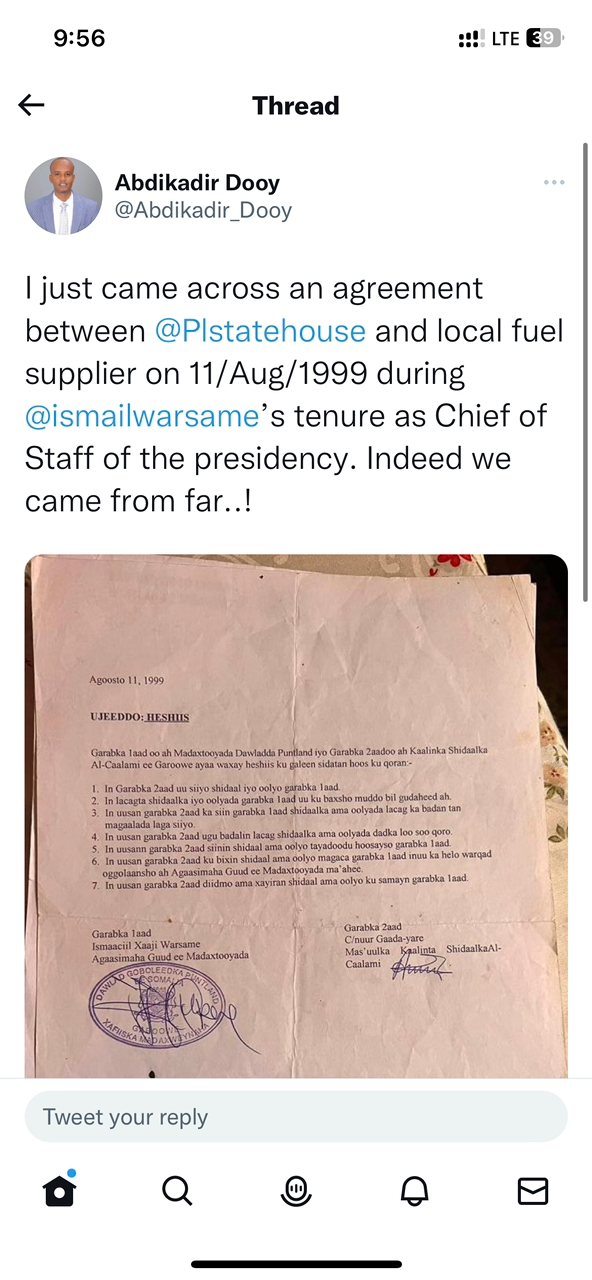

[COURTESY to Abdikadir Dooy]

LOOKING BACK AT SOMALI HISTORY

WHY SOMALIS SHOULD BE WORRIED BY MARCH OF HISTORY

Nearly 6 decades have passed since Somalis made first missteps in their attempts to create a strong nation-state. They blame a few things for their misfortune: Neo-colonialism, tribalism and religious sectarianism. They never find faults in their ways of life and attitudes towards collective bargaining. They are adverse to critical thinking and unemotional take of stuff they deal with on daily basis is amazing. They are quick to self-defence and don’t go half-way to consider other party’s interests. They don’t appreciate the ingenuity and entrepreneurship of their rivals in every field of human endeavors. Clan rivalries over centuries had created a peudo-culture of cynicism towards each other. In politics, they don’t agree on anything, even among long-term friends and school classmates. One may tempted to consider this phenomenon as egalitarianism, but think how destructive it may be to discover people who couldn’t agree on their own common good. Many of them don’t understand the importance of these statements and to ask questions about the way they live and upbring their offsprings could put you in trouble, citing convenient religious messages to avoid accountability. They desire for everybody to fail. Isn’t this a recipe for failure for all?

Note, time and history aren’t waiting for you to put your house in order. History marches on with or without you. A nation, nationality and race are like company businesses – if they don’t compete, they die and give way to the rise of more adventurous and successful entrepreneurs. It is already happening here with foreign troops in our country because we couldn’t govern ourselves, we have defenseless, porous and stretched borders with our historical enemies, and unguarded longest coastline in Africa, and most unfortunately, we have merceless extremists tearing us apart and inside out, and with no agreed upon public policy and strategy to fight back. Our political leaders have no vision beyond staying on under their poorly performing titles. Our traditional elders no longer represent fair arbitration within subclans. Some of them desire to keep their entitlements while acting as politicians/king makers, turning famed tribal mechanism for conflict resolution upside down. Our intellectuals produce no more than internet chat rooms to spread gossips and uninformed personal opinions. Our traditional nomadic life is deeply impacted by globalization of plastic vessels (containers) and dangerous habit of Qat chewing among herders. Worst of all, our social sector is broken with education suffering from lowest quality as a result of unscrupulous entrepreneurs caring only the business bottom line taking over with mass printing of fake graduation certificates. Somalia now exports sick population to India, Turkey, Kenya, among others, for basic medical care. We don’t even listen to each other without foreign intervention. We talk past each other. We have been left behind long time ago. Can we mend things together to try do some catching-up?

HISTORICAL FACT FOR ALL TO NOTE

Abdullahi Yusuf (RIP), the Late President of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was a Somali leader that had the greatest impact on Somalia’s political scene historically. What Somalis are doing and debating on now is his work in terms of governance, federalism, construction of federal member states, fighting extremism, religious sectarianism etc. Truly, he was a historical giant, whether all Somalis are willing to accept, honor him or not.

Nobody could come near him, whether it was Sayed Mohamed Abdulle Hassan or Siyad Barre.

Abullahi Yusuf was the founder of the 2nd Somali Republic (The Federal Republic of Somalia). He was the first Somali leader who formed and led the First Somali Opposition Front ( the Somali Salvation Democratic Front SSDF) against the Military Dictatorship of General Mohamed Siyad Barre with a vision to transform Somalia into a democratic state. He later founded Puntland State of Somalia, the first federal member state, before becoming the president of the Transitional Federal Government, the TFG (current Somali Federal Republic). Under his watch, needs assessment research for Somalia’s reconstruction and development Program (RDP) was launched by the UN and World Bank, leading to the New Deal by international donor community signed in Brussels with the pledge of US$2 billion. It was based on that research. It came through later as Somali government was recognized after transition.

We are reminding people of this historical fact, in response to a WDM Subscriber, who has raised the issue in another context.

Have your say.

SOME SOMALI HISTORY EXPLANTIONS AND FACTS

Questions:

- Why did Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, the late president of the Transitional Federal Government, propose to the late president of Somaliland, Mohamed Ibrahim Egal, to seek the post of Somalia’s president, given the fact Mr. Yusuf had been struggling all his life to become the President?

- Why did friends-officers, Col. Abdullahi Yusuf and General Mohamed Farah Aydid couldn’t agree to unite USC–SNA and SSDF to form a united national government?

- How history would treat the leaders of Somali National Movement ((SNM)? These and more will be exposed in this short story.

It is generally agreed Abdullahi Yusuf was extremely ambitious to become one day Somali president and that he had been working hard towards that goal in all his adult life. Becoming a rebel SSDF leader in exile in Ethiopia after a failed coup is part of his struggle to attain the goal. When the Somali Republic had failed, he saw diminishing returns for that dream of ever becoming a Somali president. Here re-instating the failed state of Somalia became his top priority, using any means to realize the foundation of the 2nd Somali Republic.

Establishment of Puntland State is a major part of that political vision. Abdullahi Yusuf saw the territorial disputes on Sool and Sanaag between Puntland and Somaliland as an obstacle to Somali unity and persistent factor for security instability in Northern Somalia (Puntland and Somaliland). He approached Late Mohamed Ibrahim Egal for peaceful resolution of the issue, including encouraging the latter to seek post of Somalia’s president. Despite Egal’s known bold past decision-making, he couldn’t dare to confront Somaliland public, who in delusional way, bought into the idea of “gooni Isutaag (secession from Somalia). At the time the Head of the BBC Somali Language Section, Patrick Gilkes, told the author of this article that Mr Egal couldn’t stay President of Somaliland one day more, were he to return to the issue of Somaliweyn politics.

General Aideed of USC and Abdirahman Tuur of SNM had conspired with Mengistu Haile-Mariam of Ethiopia to overthrow the already dying regime of Siyad Barre, and split the spoils of Somali State among their factions in Mogadishu and Hargeisa. It was agreed that in post-Siyad Barre, power would be shared between Hawiye and Isaak. Darood would be marginalized in this power grab. This is how and why Abdullahi Yussuf and Aideed couldn’t strike a deal.

When talking about the issue of “Somaliland”, in reality, people don’t appreciate the difference between Isaak clans and the rest of other clan system of Harti (Mainly Dhulbahante and Warsangeli), Issa, Samaroon (Gadabursi) that technically constituted the former British Protectorate of Somaliland. By the way, Dhulbahante clan wasn’t a party to that Protectorate arrangement as they were conquered by the British Military Administration with the help of Isaaks’ British conscripts and help.

Now, the leaders of rebel SNM, expressing real and perceived grievances against the politicians and officials of former Italian Protectorate, represented only the interests of Isaak. Somaliland is now nothing more than an Isaak identity. Many of SNM leaders were former officials of Somali Republic, who had contributed to its progress, turning up against it in the end. How history would treat them is to be seen.

THE RICHEST MAN IN HISTORY

HISTORY: 3RD ANNIVERSARY OF PUNTLAND FOUNDATION WAS ABORTED

By Ismail Warsame

Opinion Columnist

Puntland opposition elements and most titled elders couldn’t differentiate between the dislike they have for the State President of the day and significance of Puntland 3rd ANNIVERSARY. A group of traditional elders led by the Late Islaan Mohamed Islaan Muse opposing State President, Abdullahi Yusuf, had rebelled against holding the 3rd Anniversary of Puntland establishment as the first pillar of Federal Somalia. Their issue wasn’t against the State per se, but they had resisted holding the ceremony due to their opposition to the President at the time in the backdrop of a constitutional crisis. The incident alarmed people of Puntland that the modest achievements by then the new regional state were down the drain. This incident was also one of ugliest and toughest times in Puntland short history of statehood.

The Late Islaan Mohamed summoned the so-called “Kabo-Silik” (Boot-wired men), armed countryside youth, to Garowe City and ordered them to dismantle ceremonial decorations and facilities in Garowe Central Square unofficially known “Ciise Ku Caroh” (Issa’s Anger Square.) To avoid unnecessary loss of lives and to descalate the tension in town, Puntland Government abandoned the idea of marking the Day.

This history of Puntland State is closely linked to the conspiracies against Puntland by President Ismail Omar Ghueleh of Djibouti, Issayes Afewark of Eritrea and Abdulqasim Salad Hassan (Ina Salad Boy)/Ali Khalif Galaydh of Djibouti- sponsored Transitional National Government of Somalia (TNG.)

Those political developments eventually led to the brief collapse of Puntland Government. It was towards the end of year 2002 that Puntland Government was able to reinstate itself in an operation called “Restore Puntland Stability”.

Here is the record of what was happening then: