No Trust, No State: Somalia Cannot Be Built on Suspicion and Political Deceit

In Somali culture, there is an old measure of trust: Can you eat from the same plate?

If you cannot share food, you cannot share power. If you cannot trust each other’s intentions over a meal, you cannot co-author a constitution.

Somalia today suffers from a catastrophic collapse of public trust and an equally dangerous collapse of personal trust among its leaders. And without trust, there is no state-building. There is only maneuvering. There is only survival politics. There is only tactical alliances built on sand.

At the center of this political paralysis sits President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud—a man now confronting the twilight of credibility. Let us be frank: some of the political damages done during this administration are not easily reversible. Some may be irreversible. Pretending otherwise is intellectual dishonesty.

And WAPMEN does not trade in dishonesty.

The Political Damage Is Real — And Deep

The damage is not abstract. It is structural.

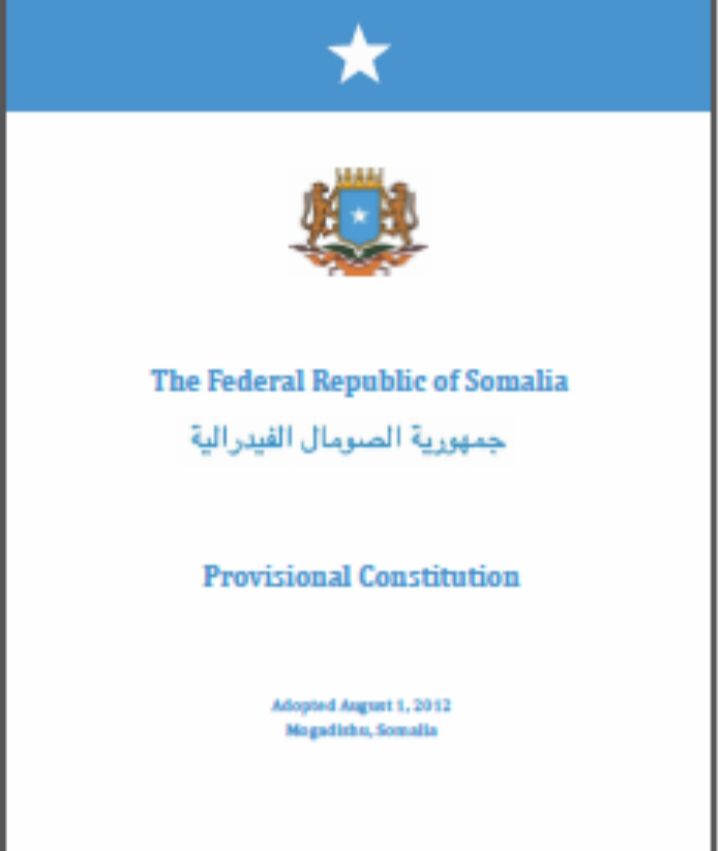

The erosion of consensus around the Provisional Constitution of Somalia.

The political manipulation of federal institutions.

The sidelining of genuine federal dialogue.

The use of selective legality as a weapon.

The transformation of Mogadishu into a city-state power center rather than a neutral federal capital.

These are not minor policy disagreements. These are foundational fractures.

Somalia is not failing because it lacks conferences. It is failing because it lacks sincerity.

And here is the clearest evidence that the lesson has not been learned:

The very fact that President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud is still dictating the venue for the meeting between Golaha Mustaqbalka Soomaaliyeed and the Presidency shows he has not grasped how deeply things have deteriorated.

When trust collapses, neutrality becomes the first currency of repair. Venue matters. Symbolism matters. Process matters. If you insist on controlling even the location of the table, you are signaling control—not reconciliation.

A leader who understands the gravity of the moment would offer neutral ground. He would decentralize the optics. He would lower himself in order to lift the nation.

Instead, we are witnessing insistence.

And insistence is not leadership. It is denial.

Constitution-Making Without Trust Is Political Theatre

Let us say it clearly:

You cannot amend a constitution unilaterally and then ask your rivals to respect it.

The 2012 Provisional Constitution was a political settlement. It was not perfect, but it was consensual. It was a ceasefire document between competing visions of Somalia. Any late amendments introduced without broad agreement must be annulled.

If not, what message is sent?

That power defines legality.

And once that principle is accepted, federalism collapses—not because of ideology, but because of insecurity.

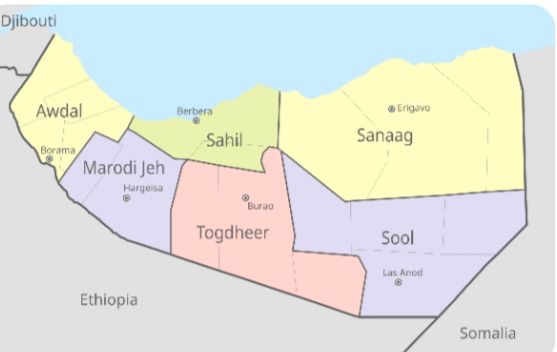

Federal Member States: Legitimacy Is Not Optional

Another uncomfortable truth: leaders of Southwest, GalMudug, and Hirshabelle must secure democratic legitimacy.

If federal member state presidents are seen as products of manipulated processes, then they become extensions of Mogadishu’s executive rather than autonomous constitutional actors.

Federalism cannot survive if federal member states are administratively dependent satellites.

Legitimacy must come from:

Transparent processes

Competitive political participation

Clear mandates from their constituencies

Without that, trust collapses further.

The Minimum Steps to Prevent Collapse

If Somalia is to remain one country—even in its current fragile form—three immediate corrections are unavoidable:

1️⃣ Democratic Legitimacy in Southwest, GalMudug, and Hirshabelle

No more shortcuts. No more managed outcomes.

2️⃣ Annulment of Late Amendments to the 2012 Constitution

Return to the last consensual baseline. Reset the clock.

3️⃣ Inclusive, Consensus-Based Federal Elections

No exclusion games. No selective invitations. No predetermined outcomes.

Anything short of this will not cut.

The Hard Truth: Status Quo Is Already in Danger

There is an illusion circulating in Mogadishu that Somalia can be governed through fatigue—that opponents will eventually surrender out of exhaustion.

That illusion is dangerous.

Federalism in Somalia was not born in comfort. It was born out of civil war realities. It was a de facto settlement long before it was a de jure document. It cannot be dismantled by political cleverness.

When leaders cannot eat from each other’s plate, they cannot build institutions together. When they suspect each other of traps in every meeting, negotiations become performances.

And Somalia cannot survive on performances.

A Personal Reckoning Required

The burden lies first with President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud.

Statesmanship is not stubbornness.

Authority is not infallibility.

Leadership is not theatrical dominance.

If he does not put everything on the table—every amendment, every grievance, every power maneuver—there will be no repair.

And without repair, Somalia risks drifting into a silent constitutional collapse where institutions exist on paper but legitimacy evaporates in reality.

Final Word

No trust.

No neutral table.

No shared constitution.

No shared state.

Somalia stands at a narrow bridge between repair and rupture. It will not be repaired by speeches. It will not be repaired by controlled conferences.

It will be repaired only by honesty, legitimacy, and consensus.

Anything short of that will not cut.

——

Support WAPMEN — the home of fearless, independent journalism that speaks truth to power across Somalia and the region. Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081

You must be logged in to post a comment.