Executive Summary

This policy paper examines the legal status of colonial-era treaties between the British administration and northern Somali clans and assesses their relevance to post-1991 sovereignty claims. It argues that these treaties collectively established the British Somaliland Protectorate as a colonial administrative unit, not clan-owned sovereign entities. All such treaties were extinguished by the 1960 Union of British and Italian Somaliland, transferring sovereignty to a unified Somali Republic. The collapse of the Somali state in 1991 did not revive colonial treaties nor dissolve Somalia’s international legal personality. Consequently, Somaliland cannot obtain international recognition without Somalia’s consent through negotiation, as required by international law governing state continuity, territorial integrity, and secession.

1. Introduction

Since 1991, claims to sovereignty in northern Somalia have frequently invoked colonial-era treaties as a legal foundation for unilateral independence. This paper evaluates such claims against established principles of international law, including state succession, territorial integrity, and recognition. It demonstrates that colonial treaties do not confer enduring sovereign rights on clans and cannot be selectively resurrected to justify unilateral recognition.

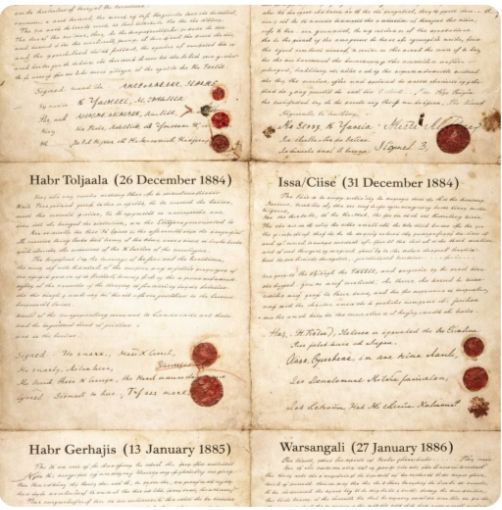

2. Colonial Treaties and the Formation of the British Somaliland Protectorate

Treaties concluded between Britain and northern Somali clans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were instruments of colonial administration. Under international law, treaties concluded between colonial powers and non-state entities did not create sovereign equals nor vest sovereignty in local signatories (Shaw, 2017; Crawford, 2006).

Collectively, these agreements constituted the British Somaliland Protectorate, whose external borders were fixed by inter-imperial agreements between Britain and Italy. They did not:

Create independent clan states

Transfer sovereignty to clans

Establish inheritable territorial title

Colonial sovereignty resided exclusively in the administering power.

3. Dhulbahante Territory and Colonial Incorporation by Occupation

Dhulbahante territories were incorporated into the Protectorate through colonial occupation, following the defeat of Sayid Mohamed Abdulle Hassan and the collapse of the Dervish Movement. International law recognizes occupation as a lawful mode of colonial territorial acquisition during that period (Shaw, 2017).

This history confirms that the Protectorate was not a voluntary confederation of clans but a colonial construct established through mixed methods of treaty and force.

4. Colonial Borders vs. Clan Borders

International law distinguishes between administrative colonial borders and internal social or customary boundaries. Colonial borders defined the territorial scope of the colony for purposes of administration and later state succession; they did not abolish internal communal land tenure or clan territoriality (Crawford, 2006).

The principle later known as uti possidetis juris preserved colonial administrative borders at independence to prevent conflict—not to reallocate internal ownership or sovereignty (ICJ, Burkina Faso v. Mali, 1986).

5. Legal Extinguishment of Colonial Treaties by the 1960 Union

Upon independence and union in 1960, sovereignty passed from the colonial administrations to the Somali Republic as a single successor state. Under the law of state succession:

Colonial treaties lapse unless expressly preserved

Sovereignty vests in the successor state, not sub-state entities

Internal groups do not retain a right of unilateral withdrawal

This position is consistent with the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978) and customary international law (Crawford, 2006).

6. Post-1991 Collapse and the Continuity of the Somali State

The collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991 did not terminate Somalia’s international legal personality. Under international law, statehood is not extinguished by governmental collapse (continuity doctrine). Somalia retained UN membership, treaty capacity, and territorial integrity (Shaw, 2017).

The International Court of Justice has repeatedly affirmed that internal instability does not dissolve statehood (Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall, Advisory Opinion, 2004).

7. Recognition, Secession, and the Requirement of Negotiated Consent

International law strongly disfavors unilateral secession from an existing sovereign state. Outside the context of decolonization, recognition of a breakaway entity requires the consent of the parent state, except in exceptional cases of remedial secession.

In its Kosovo Advisory Opinion (2010), the ICJ deliberately avoided recognizing a general right to unilateral secession and emphasized the primacy of territorial integrity in relations between states.

Somaliland’s case does not qualify as:

Decolonization (self-determination was exercised in 1960), nor

Remedial secession (no sustained denial of internal self-determination meeting the high threshold recognized in doctrine)

Accordingly:

Somaliland cannot lawfully obtain international recognition without Somalia’s consent

Such consent can only arise through formal negotiation with the internationally recognized Somali state

Recognition absent consent would violate Somalia’s territorial integrity under UN Charter Article 2(4) and UN General Assembly Resolution 2625 (1970)

International practice—from Sudan/South Sudan to Ethiopia/Eritrea—confirms that negotiated separation, not unilateral declaration, is the lawful pathway.

8. Policy Implications

For Somali stakeholders:

Sustainable political outcomes must be negotiated, inclusive, and legally grounded. Colonial reinterpretation offers no lawful shortcut.

For international actors:

Recognition without Somalia’s consent would contravene settled international norms and set a destabilizing precedent.

For mediation frameworks:

Dialogue should focus on negotiated constitutional or confederal arrangements rather than unilateral recognition strategies.

9. Conclusion

Colonial treaties in northern Somalia established a colonial administration, not sovereign clan entities. These treaties were extinguished by the 1960 Union, transferring sovereignty to a unified Somali state. The 1991 collapse did not revive colonial arrangements nor authorize unilateral secession.

Somaliland cannot secure international recognition without Somalia explicitly letting it go through negotiation. Any alternative approach lacks legal foundation and contradicts international law on state continuity, territorial integrity, and recognition.

References (International-Law Sources)

Crawford, J. (2006). The Creation of States in International Law (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Shaw, M. N. (2017). International Law (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

International Court of Justice (1986). Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso v. Mali), Judgment.

International Court of Justice (2004). Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion.

International Court of Justice (2010). Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo, Advisory Opinion.

United Nations (1945). Charter of the United Nations, Article 2(4).

United Nations General Assembly (1970). Resolution 2625 (XXV): Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations.

Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978).