Somali politics has long been a theater of the absurd, but the latest act—featuring Puntland’s Said Abdullahi Deni and Jubaland’s Ahmed Madoobe—plays less like a strategic alliance and more like a mismatched sitcom. The scene is set: two rivals compelled to share a stage not by shared vision or belief in a greater Somalia, but by the unifying pressure of Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s Damul Jadiid regime.

Deni, the perennial aspirant, still chases the Villa Somalia mirage with the desperation of a man dying of thirst. The sting of 2022, when Madoobe abandoned him at the political altar, remains fresh. Yet in Somali politics, betrayal is the coin of the realm. Now, Deni has no choice but to place his bets on the very man who shattered his ambitions. The smile he offers Madoobe is not one of friendship, but of grim resignation—the look of a gambler who knows the dice are loaded but rolls them all the same.

Across the table, Ahmed Madoobe operates in pure survival mode. He has perfected the art of outlasting regimes without committing to a single, meaningful principle. His alliances are like sandcastles on the shores of Kismaayo: meticulously built at high tide, only to be washed away by the morning sun. Is he reliable? He is steadfast only in his own self-interest. To allies and adversaries alike, he is a political mirage—shimmering with promise from a distance, dissolving into nothing upon approach.

Presiding over this spectacle from Villa Somalia is Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, a leader slowly and publicly deflating. By May 2026, he will not be a symbol of authority but an empty vessel, hissing with the last gasps of influence. His legacy is already settling as a fine dust of governance failures, corruption, and the hollow projects of Damul Jadiid. Even his traditional Hawiye base is fractured, leaving him isolated and exposed.

What is most striking amid this political circus is the profound vacuum at its center. Somalia’s battered governance has no credible successor waiting in the wings. The Deni-Madoobe pact is not a roadmap to a better future; it is a detour into the politics of mutual necessity. It is the politics of “for now,” a temporary ceasefire in a war of all against all.

The Somali people deserve visionaries, but they are perpetually handed gamblers, opportunists, and fading icons. The only certainty is that this alliance will end as all such arrangements in Somalia do: with concealed knives beneath the table, polished smiles for the cameras, and history repeating itself in a farce of forgotten promises.

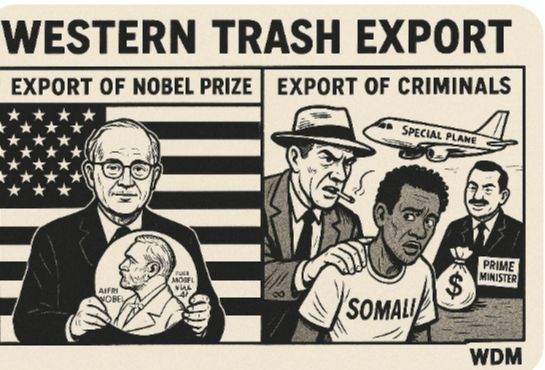

WDM Verdict: This is not the birth of a coalition. It is the sight of two political fossils huddling for warmth against the cold wind of public discontent, while the Damul Jadiid regime implodes from the vacuum of its own failed leadership.

You must be logged in to post a comment.