September 9, 2025

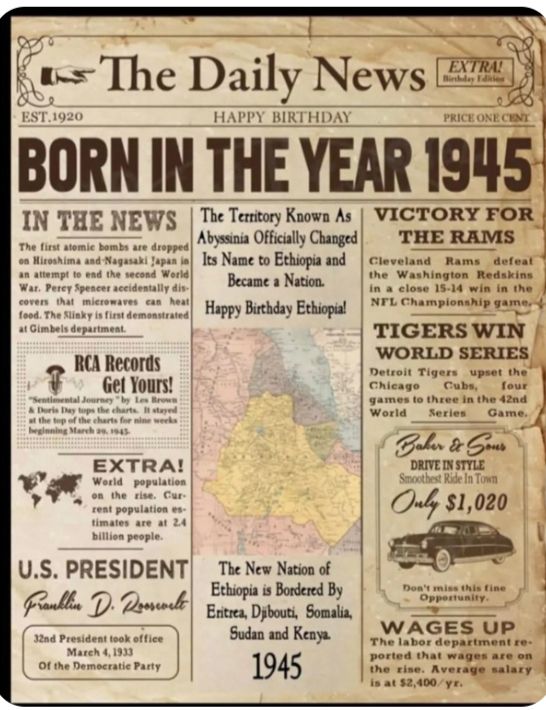

A discovered newspaper clipping from 1945 is more than an artifact of nostalgia—it is a piece of propaganda preserved in parchment. It boldly declares that the territory known as Abyssinia “officially changed its name to Ethiopia and became a nation.” This seemingly innocuous statement is a political earthquake, for it exposes the foundational deception that has sustained one of Africa’s most potent and enduring myths: the idea of Ethiopia as an ancient, continuous, and unified nation-state.

Deconstructing the Myth of Timelessness

For generations, a powerful narrative—championed by Western orientalists, historians, and the Ethiopian imperial court itself—has been meticulously woven. It portrays Ethiopia as the world’s oldest Christian kingdom, a timeless polity that miraculously escaped the Scramble for Africa and emerged into the modern world with its ancient sovereignty intact. This narrative served a purpose: it provided a symbol of Black resistance and pride in a colonized continent.

However, the 1945 clipping slyly admits a different truth. “Ethiopia” was, in a crucial modern sense, invented—a consciously manufactured nation-state project imposed upon a diverse constellation of conquered peoples. The adoption of the name was not an organic evolution but a strategic act of political rebranding.

From Abyssinian Empire to Ethiopian Nation-State

Until the mid-20th century, the core political entity was more accurately termed the Abyssinian Empire. This was a highland kingdom dominated by Amhara and Tigrayan feudal elites, whose expansionist ambitions were rooted in the concept of “Restoration of the Solomonic Empire.” It was never a nation in the modern sense of a voluntary social contract among a cohesive people, but an empire forged through relentless conquest.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, under Emperors Menelik II and Haile Selassie, Abyssinia embarked on a violent campaign of southern, eastern, and western expansion. It swallowed entire nations and kingdoms: the Oromo nations, the Somali Sultanate of Ajuran, the Sidama kingdoms, the Afar sultanates, and the peoples of Gambella and Benishangul, among many others. This process, known as “Agar Maqnat” (land grabbing), was not one of integration but of subjugation. It was achieved through the blood of massacres (e.g., Anole, Chelenko), the imposition of feudal land tenure (gebbar system), and cultural erasure.

Therefore, the 1945 proclamation was not a birth of freedom but the codification of conquest. It was the moment the empire, having been restored after the brief Italian interlude, sought to shed its explicit imperial skin and don the modern garb of a unified nation-state, thereby legitimizing its annexed territories as innate parts of a whole.

The Geopolitical Baptism: A Convenient Fiction for the Post-War Order

The timing was no accident. The end of World War II and the dawn of the Cold War created a perfect storm of geopolitical opportunism. The West, eager to crown an African “exceptionalism” and secure a stable, loyal Christian outpost in the strategically vital Horn of Africa, willingly accepted the fiction.

The League of Nations had disgraced itself by its feeble response to Mussolini’s invasion in 1935. Restoring Haile Selassie was not just an act of justice; it was an opportunity for a reset. The empire was not restored as a multi-national entity but rebranded as a singular state—“Ethiopia.” This new-old name, with its classical and biblical resonances, was palatable and impressive to Western audiences.

This suited the powers of the nascent United Nations perfectly. Ethiopia was ushered in as a founding member in 1945, held up as Africa’s showcase state, all while Somali territories (the Ogaden), Eritrea (federated and later annexed), and Oromo lands languished under a system of enforced assimilation and centralization. The Cold War demanded stable, anti-communist allies, not messy ethnographic truths. Washington and London needed Ethiopia to be eternal, indivisible, and Christian—a bulwark against Soviet influence. Thus, they stamped the Abyssinian Empire’s new passport with the name “Ethiopia” and collectively agreed to call it ancient.

Cartographic Violence: Erased Nations, Silenced Histories

A closer look at the accompanying map is instructive. It describes Ethiopia as “bordered by Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, and Kenya.” This external framing reinforces the illusion of a natural, pre-existing unit. But the true violence lies in the internal silence.

What of the nations within? The Oromo, who likely constitute the largest ethnic group and whose language and history were suppressed for a century? The Somali of the Ogaden, forcibly incorporated in 1887 and whose aspirations for self-determination have been met with brutal repression in every subsequent decade? The Sidama, Afar, Gambella, Wolayta, and dozens more—each with their own rich histories, governance systems, and identities—were all reduced to mere provinces (teklay gizats) on a map, their very existence subsumed into a “new nation” born without their consultation or consent.

This cartography is not neutral; it is violence disguised as ink. It is the ultimate tool of the imperial project: to make the conquered lands and peoples disappear into the homogenizing fabric of the state, making rebellion seem like secession from a natural whole rather than resistance against an unnatural union.

The Inevitable Political Reckoning: The Empire Strikes Back

The foundational lie of 1945 haunts the Horn of Africa to this day. A state built not on consent but on conquest is inherently brittle. Every major conflict in modern Ethiopian history is a direct manifestation of this original sin:

· Eritrea’s 30-year war of independence (1961-1991) was a direct rejection of Haile Selassie’s abrogation of their federal arrangement.

· The Oromo liberation struggle, ongoing for decades, is a fight against political and cultural marginalization.

· The Ogaden rebellions are a continuous demand for Somali self-determination.

· Even the recent Tigray War (2020-2022), while complex, features elements of a core region (Tigray) that once dominated the imperial project clashing with a central government it no longer controls.

Ethiopia was not born in 1945; it was imposed. That imposition created a façade of unity, perpetually cracked by the unresolved questions of national self-determination and the empire’s refusal to genuinely transform into a voluntary multinational federation.

Conclusion: A Confession Wrapped in a Celebration

This map and its celebratory headline—“Born in the Year 1945”—should not be read as a simple historical record. It is a confession. A confession that Abyssinia’s rebranding was a calculated, modern act of statecraft—a colonial-style reorganization of an internal empire to suit a post-colonial world order.

It is a birthday card for a lie. A lie that erased nations, legitimized conquest, and planted the seeds for perpetual war. The lesson is clear: the modern Ethiopian state was not born; it was manufactured. Until the peoples within its borders can openly confront this history and renegotiate their coexistence on terms of mutual respect and genuine equality—rather than continued domination by any center—the empire will remain a ticking time bomb, wrapped in the fraying parchment of a “timeless” myth.