By Ismail H. Warsame, PhD Candidate, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Table of Contents

1. Abstract

2. Introduction

3. Historical Context of Somali State Fragility

4. The Garowe Debate: An Ethnographic Vignette

5. Civic Education in Theory and Practice

6. The Somali Case: Civic Collapse and Informal Substitutes

7. Consequences of Civic Deficits for Somali Federalism

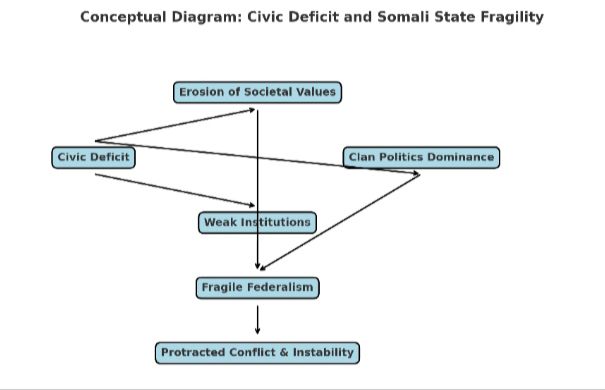

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Civic Deficit and State Fragility in Somalia

8. International Actors and the Civic Question in Somalia

9. Civic Education as Nation-Building: Pathways Forward for Somalia

10. Conclusions and Recommendations

11. References

Abstract

Somalia’s three-decade state crisis is often attributed to clan conflict, foreign intervention, or elite predation. This dissertation argues, however, that beneath these explanations lies a less explored but critical factor: the collapse of civic education and the erosion of shared societal values. Drawing on an ethnographic vignette from Garowe, complemented by historical analysis and theoretical framing, this study examines how deficits in civic education have undermined Somali federalism, exacerbated clan dominance, and hindered democratic participation. While acknowledging the limitations of its evidence base, the study advances a model of “civic deficit” as a driver of state fragility. It also considers counter-arguments about causality, explores indigenous civic traditions, and assesses the challenges of implementing civic education in a fragmented polity. The conclusion outlines pathways for a Somali-specific civic curriculum that synthesizes clan, Islamic, and modern state identities, positioning civic education as an indispensable tool for nation-building.

1. Introduction

Where did Somalia’s troubles begin? In a Garowe internet café, students and teachers debated whether the country’s crisis began with Aden Adde’s refusal to let Western powers explore Somali resources, or with the Arta Conference of 2000. Yet the true answer, this dissertation argues, is deeper: Somalia faltered when it abandoned civic education and the cultivation of societal values.

This dissertation explores the link between civic deficits and state fragility in Somalia. It does so through historical analysis, ethnographic observation, and theoretical engagement with civic education. It proposes that civic collapse was both a cause and a consequence of state failure, producing a vicious cycle that continues to undermine federalism today.

2. Historical Context of Somali State Fragility

Somalia’s postcolonial trajectory was shaped by missed opportunities. The democratic optimism of the 1960s collapsed under military dictatorship, while Siad Barre’s regime manipulated clan loyalties even as it modernized education. The state’s implosion in 1991 produced decades of civil war, fragmentation, and warlordism.

Most scholarship focuses on clan conflict, war economies, and foreign interventions. Yet hidden in the background was the slow erosion of civic identity. The collapse of public education removed the institutional base for cultivating civic virtues. What emerged instead was a generation socialized through war, displacement, and fragmented authority, devoid of the shared civic reference points necessary for statehood.

3. The Garowe Debate: An Ethnographic Vignette

In 2024, inside a Garowe café filled with young men and women hunched over laptops, a debate raged: when did Somalia’s troubles begin? One declared Aden Adde was to blame; another insisted the Arta Conference was the turning point. For ninety minutes, opinions clashed. Yet none raised the issue of civic education or the values once taught in schools and homes.

This vignette is evocative, but it is not exhaustive. It reflects discourse in Garowe — a city in Puntland that has enjoyed relative stability compared to Mogadishu or Beledweyne. As such, the vignette is best read as an illustrative microcosm rather than a comprehensive account. Broader ethnographic work across Somalia would be needed to generalize its findings. Nonetheless, it crystallizes the gap this dissertation addresses: the invisibility of civic education in Somali public debates.

4. Civic Education in Theory and Practice

Civic education refers to the cultivation of the knowledge, skills, and values necessary for democratic participation and national belonging. In many societies, it is taught through schools, media, and public rituals.

In Somalia, however, the term must be defined carefully. A distinctly Somali civic education would need to engage three intersecting domains:

1. Clan identity (qabiil) – the enduring basis of belonging and loyalty.

2. Islamic principles – the moral compass of Somali society.

3. Modern citizenship – the constitutional ideal of equal participation in a federal state.

A viable framework would weave these strands into a Religious-Civic Synthesis, aligning Qur’anic ethics, Somali customary values, and constitutional principles. Anything less risks alienation.

5. The Somali Case: Civic Collapse and Informal Substitutes

The 1991 collapse destroyed formal civic education, but informal mechanisms persisted. Poetry (maanso) continued to teach moral lessons; clan assemblies (shir) provided forums for deliberation; Qur’anic schools (dugsi) instilled ethical discipline.

Yet these forms, while vital, were insufficient for national integration. They nurtured strong local identities but failed to scale upward into a cohesive civic consciousness. Somalis became civic-rich locally but civic-poor nationally.

This tension helps explain why federalism remains fragile: without a unifying civic narrative, political identity defaults to clan, not state.

6. Consequences of Civic Deficits for Somali Federalism

Civic deficits have several consequences:

Weak Institutions – Laws are contested not on civic grounds but on clan allegiances.

Dominance of Clan Politics – Federal institutions are arenas of clan competition, not citizen representation.

Fragile Federalism – Lacking civic glue, federal states oscillate between autonomy and secession.

This relationship can be visualized through a conceptual model (Figure 1), which traces how the erosion of civic education cascades into institutional weakness, clan dominance, and ultimately state fragility.

A note of caution is necessary: civic decline may not be the sole cause. One could argue that state collapse made civic education impossible, making it an effect rather than a cause. The more accurate interpretation is cyclical: state collapse and civic decline reinforce one another in a vicious loop.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Civic Deficit and State Fragility in Somalia

(Author’s elaboration)

7. International Actors and the Civic Question in Somalia

Donors and external actors have heavily invested in Somalia’s state-building: elections, constitutions, and federal negotiations. Yet they have largely ignored the civic dimension, assuming that technical institutions could substitute for civic trust.

International NGOs occasionally sponsor civic programs, but these are sporadic, donor-driven, and rarely adapted to Somali realities. Moreover, civic education framed as “secular” often provokes resistance from religious constituencies, inadvertently fueling suspicion rather than legitimacy.

8. Civic Education as Nation-Building: Pathways Forward for Somalia

Rebuilding Somalia requires civic education that is contextually grounded and practically feasible. Recommendations include:

1. Curriculum Development – Design a national framework that integrates clan, Islamic, and modern civic values.

2. Religious-Civic Integration – Partner with religious leaders to legitimize civic teaching within Qur’anic frameworks.

3. Regional Flexibility – Allow federal member states to tailor curricula within a national framework.

4. Phased Implementation – Begin in stable regions, while developing contingency models for insecure zones.

5. Community Participation – Civic education should not only be top-down (schools) but also bottom-up (local assemblies, poetry, radio).

Practical challenges remain. Al-Shabaab will resist any civic initiative. Regional autonomy complicates curriculum design. Teachers need retraining, and resources are scarce. Yet these hurdles should not deter reform; they underscore the need for sequencing, creativity, and political will.

9. Conclusions and Recommendations

Somalia’s fragility cannot be explained by clan politics alone. Beneath the surface lies a civic vacuum — a deficit of shared values and educational foundations that could bind citizens to the state.

This dissertation makes four contributions:

1. It identifies civic deficit as a key driver of Somali state fragility.

2. It demonstrates how informal civic forms persisted but failed to scale to the national level.

3. It situates the Somali case within global debates on civic education, showing the need for contextual adaptation.

4. It offers a framework for a Somali-specific civic curriculum that integrates clan, Islam, and citizenship.

Future research should broaden ethnographic evidence beyond Garowe, test the cyclical causality model more rigorously, and explore the politics of implementing civic education in insecure zones.

In sum, without civic education, federalism in Somalia will remain fragile scaffolding on a hollow foundation. With it, however, Somalia may yet build a durable state.

References

Ahmed, I. I. (1999). The Heritage of War and State Collapse in Somalia and Somaliland: Local-level Effects, External Interventions and Reconstruction. Third World Quarterly, 20(1), 113–127.

Ali, A. (2015). Clan, Religion, and the Failure of Somali State Reconstruction. African Affairs, 114(456), 1–23.

Barakat, S. (2010). Understanding Somali Identity: Tradition, Religion, and Modernity. Conflict Studies Quarterly, 8, 45–67.

Elmi, A. A. (2010). Understanding the Somalia Conflagration: Identity, Political Islam and Peacebuilding. Pluto Press.

Lewis, I. M. (2008). Understanding Somalia and Somaliland: Culture, History, Society. Columbia University Press.

Samatar, A. I. (2016). The Dialectics of Piracy in Somalia: Historical Materialism and Globalization. Review of African Political Economy, 43(150), 23–41.

UNESCO. (2011). Civic Education and Peacebuilding in Post-Conflict Societies. Paris: UNESCO.

You must be logged in to post a comment.