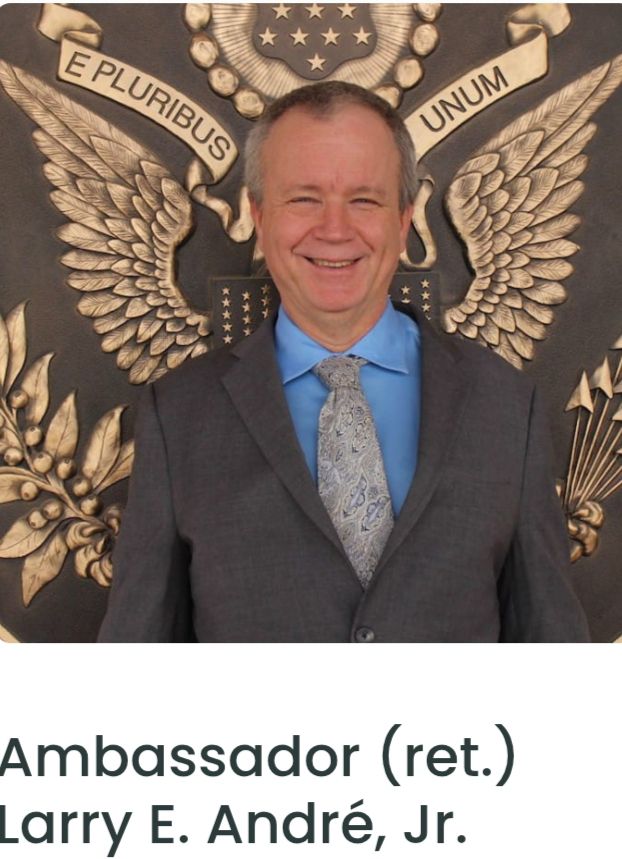

Ambassador Larry André’s piece is a thoughtful, sober, and experience-driven analysis of one of the Horn of Africa’s most contentious political issues: the status of Somaliland. Drawing on decades of diplomatic engagement in Somalia, Djibouti, and the wider region, André calls for a measured and fact-based U.S. policy review at a time when advocacy for Somaliland recognition is growing louder in Washington.

Here is the link to the piece:

Strengths of the Article

1. Pragmatism Over Idealism

André avoids simplistic solutions. He carefully outlines three U.S. policy options—status quo, liaison office in Hargeisa, or full recognition of Somaliland—and persuasively argues for the middle ground of opening a U.S. office in Hargeisa under Mogadishu’s embassy framework. This cautious approach reflects both regional realities and U.S. strategic interests.

2. Deep Regional Context

Unlike many Western commentaries on Somaliland, André situates the issue within the complex clan dynamics of the Somali people, emphasizing that clan loyalties often outweigh national ones. His acknowledgment that the Isaaq overwhelmingly drive Somaliland independence while other clans (Dir, Darod) remain ambivalent is particularly important—and often overlooked.

3. Balanced Consideration of Facts

The article highlights uncomfortable truths on both sides. For example, André notes Somaliland’s stronger governance and stability compared to southern Somalia, but also its intolerance of pro-unionist voices, illustrated by President Bihi’s blunt admission about jailing “traitors.” Similarly, he dismisses unproven allegations about Somaliland collusion with al-Shabaab, while recognizing that Somaliland’s security partly benefits from international efforts in southern Somalia.

4. Comparative Insights

The discussion of federalism models (Canada–Quebec, UK–Scotland, Tanzania–Zanzibar) adds intellectual weight, suggesting creative constitutional arrangements as alternatives to either secession or forced unity.

Weaknesses of the Article

1. Limited Somali Voices

While André emphasizes consultation, the essay still largely reflects a diplomat’s top-down perspective. More engagement with grassroots Somali perspectives beyond political elites and business leader would have enriched the analysis.

2. Underplaying External Geopolitics

Although he briefly mentions Turkey, the UAE, and rival powers, the piece could have more fully assessed how great-power competition (China, Gulf states, Western powers) intersects with Somaliland’s recognition question, especially regarding Berbera port and Red Sea security.

3. Ambiguity on U.S. Interests

André stresses “do no harm” and regional stability, but is less clear on what concrete U.S. interests—counterterrorism, maritime security, great-power competition—would ultimately drive Washington’s decision.

Overall Assessment

This is an enlightening, cautious, and authoritative contribution to the Somaliland debate. Its greatest strength lies in tempering passionate advocacy with historical perspective, lived diplomatic experience, and a clear warning against reckless unilateralism. By urging a process rooted in consultation, facts, and creative federalist thinking, André positions himself as a voice of prudence in a debate often dominated by emotion and lobby-driven arguments.

The article does not settle the Somaliland question—but it is not meant to. Instead, it provides a framework for responsible deliberation, reminding U.S. policymakers that decisions made in Washington can carry unintended, and possibly explosive, consequences in Hargeisa, Mogadishu, and beyond.

Verdict: A must-read for anyone serious about Somali politics, U.S. Africa policy, or the geopolitics of the Horn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.