Puntland stands today at the edge of its own manufactured abyss. The supposed “stable” state in Somalia’s chaos, the self-branded “island of relative peace,” is now no more than a shaky raft patched together with old clan deals, fading loyalties, and the last drops of remittance dollars. At the center of this mess looms the biggest question no one dares to answer: what happens to Puntland’s 66-member legislature when half of its foundations are crumbling beneath it?

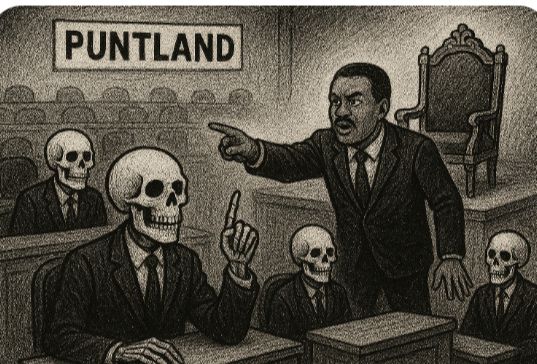

Let’s start with the facts no one in Garowe’s political salons wants to admit out loud: SSC-Khatumo is gone. Dhulbahante elders have slammed the door shut on Garowe’s pretensions. They do not want to send delegates to a Puntland House that legislates in their name. Yet Puntland’s entire arithmetic of legitimacy—the sacred number of 66—was built on their inclusion. Without SSC, the house is not just incomplete, it is illegitimate. Puntland’s legislature is becoming a parliament of ghosts, haunted by missing seats and empty loyalties.

And who is left to fill the vacuum? Certainly not the voters. The much-trumpeted democratization project, with its glittering promises of universal suffrage, is dead—buried without ceremony by a leadership that decided Garowe is not enough of a throne, that only Villa Somalia’s golden chair is worthy of ambition. Said Abdullahi Deni’s eyes are fixed on Mogadishu’s spoils, and in the process, he has left Puntland’s democratization to rot in the graveyard of broken promises. Elections in Puntland remain a hereditary lottery, reserved for those with the right bloodline and the right clan balance. Universal suffrage? A cruel joke in a state where even universal electricity and clean water are luxuries.

Meanwhile, the ground beneath Puntland burns. In the mountains of Bari and Sanaag, ISIS and Al-Shabaab are not hiding—they are nesting, multiplying, embedding themselves into the crevices of Puntland’s fragile society. The security forces are underpaid, demoralized, and busy guarding checkpoints where they shake down starving traders instead of fighting terrorists. And while Garowe politicians debate the sacred “number 66,” the real masters of the eastern mountains are carrying out recruitment drives among unemployed youth whose only alternatives are migration, piracy, or militancy.

The economic downturn has turned into a freefall. The air-money system—this Ponzi scheme masquerading as a financial sector—remains the fragile lifeline. Hard cash is gone. Bank deposits are fiction. A technical glitch in the Golis or Somtel servers could freeze the entire state into panic. The few wealthy elites are already transferring what’s left of their fortunes abroad, buying real estate in Nairobi and Dubai, while ordinary Puntlanders quietly vanish—boarding boats to Yemen, braving deserts to Libya, or taking the long road to Europe.

Urban centers are shrinking. Drive through Garowe, and you’ll feel the difference—the bustle of markets is gone, the chatter of young people replaced by silence and empty tea shops. Poverty and unemployment have reached levels that would once have sparked rebellion, but today only fuel quiet despair. Puntland is bleeding people as fast as it is bleeding legitimacy.

And yet, the political class continues its performance: the 66 seats must remain 66, even if half the members come from thin air. Empty chairs can still be counted. Ghost MPs can still vote. Legitimacy can still be fabricated with ink and stamps. This is Puntland’s political genius: to govern nothing and pretend it is something.

The tragedy is not that Puntland is collapsing. The tragedy is that it is collapsing quietly, with no drama, no great battle, no revolution—just a slow leak of people, of money, of legitimacy, of hope. By the time anyone wakes up, Puntland’s legislature will no longer represent its people but only its absence. A state of shadows, a parliament of ghosts, legislating in the name of a population that has already fled.

You must be logged in to post a comment.