Federalism: Reality vs Rhetoric1. Source of AuthorityCanadaFederal and provincial governments derive authority directly from the ConstitutionProvinces are co-sovereign in their jurisdictionsOttawa does not grant power to provincesSomaliaFederal Member States (FMS) are treated as delegated authoritiesMogadishu behaves as the source of all legitimacyPower is politically lent, then withdrawnVerdict:Canada = constitutional federalismSomalia = administrative decentralization disguised as […]

WDM EDITORIAL | WAPMEN Federal President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has reached the end of the road—politically, morally, and constitutionally. As his term drifts into twilight, what remains is not a legacy of statesmanship but a trail of institutional vandalism, constitutional abuse, and calculated contempt for Somalia’s fragile federal order. History will not remember this period […]

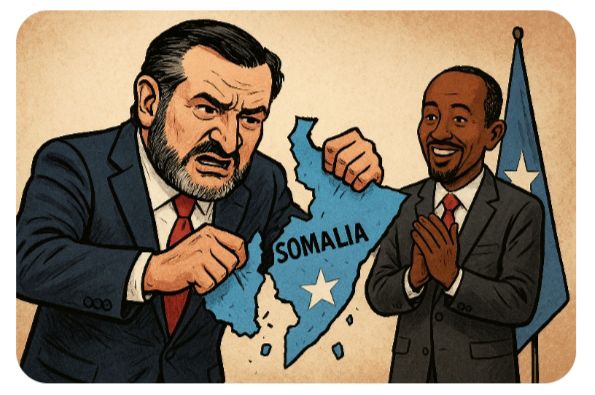

By Ismail H. WarsameWDM / WAPMENSomalia’s tragedy is not a lack of opportunity. It is the repeated, willful refusal to recognize opportunity when it lies directly beneath our feet.Many years ago, I encountered a parable titled “Acres of Diamond.” Its lesson has haunted me ever since—and nowhere does it apply more brutally than to Somalia.The […]

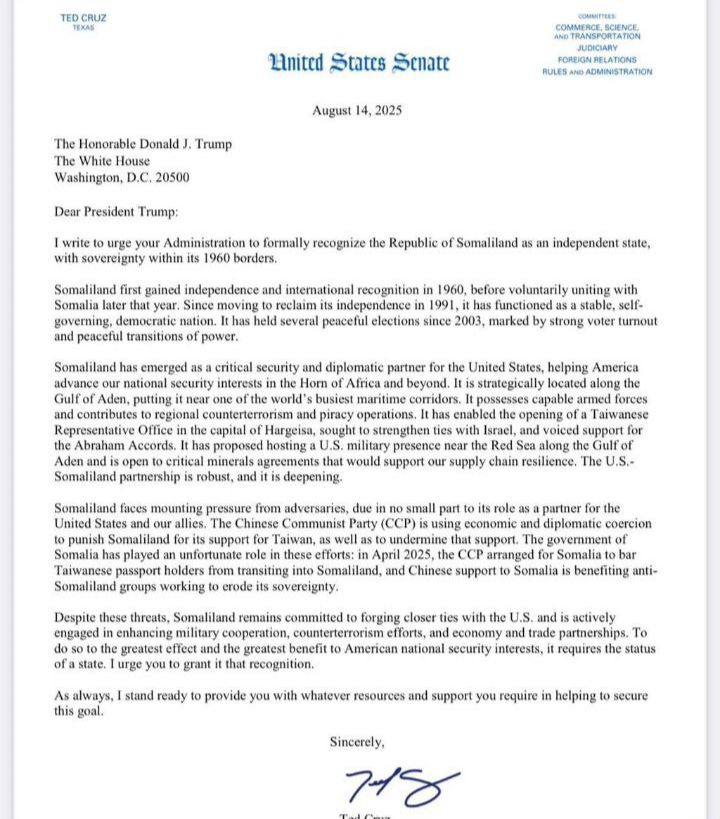

There is a dangerous myth circulating in Puntland today: that the proliferation of militias loyal to Mogadishu inside Puntland is an external conspiracy alone. That is only half the truth. The other half—more uncomfortable, more damning—is that this infiltration has been enabled by omission, neglect, and deliberate non-action by President Said Abdullahi Deni’s administration.Mogadishu did […]

Hassan Mohamed (Binge) contributed to this editorial Somalia today is not short of “forums,” “councils,” or “initiatives.” It is short of honesty.The uneasy tango between President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud and the so-called Golaha Mustaqbalka Soomaalia exposes, once again, a political culture built on deception, clannish calculations, and naked personal ambition—thinly disguised as national salvation. Let […]

A WAPMEN satirical essay Somali politics has perfected a rare art: the ability for all principal actors to win their personal battles while the country itself collapses in the background. The latest “interesting take” making the rounds claims that President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has politically defeated Puntland President Said Abdullahi Deni, while Deni, in turn, […]

To keep WAPMEN (Warsame Policy & Media Network) independent journalism strong, credible, and effective, we kindly ask for your continued support.In a volatile world—where the old international order is collapsing and Somalia faces mounting internal and external challenges—fearless, independent journalism is not a luxury; it is a necessity.Please renew your annual subscription and donate whatever […]

The Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), under President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, has once again perfected its favorite political art form: performative dialogue followed by deliberate sabotage. The latest casualty is a potential sit-down with the Golaha Mustaqbalka Soomaalia—not by accident, not by misunderstanding, but by design.At the inauguration of the SSC-KHAATUMO Administration in Laascaanod, Prime […]

Case Study 1: Food Aid vs. Agricultural Systems (South-Central Somalia) For more than three decades, Somalia has received large volumes of emergency food assistance coordinated with Western donors and multilateral agencies, often under the policy umbrellas of the European Union, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund.Yet sustained investment in irrigation along the Shabelle […]

Puntland State is not under siege because of destiny, geography, or foreign conspiracies alone. It is under siege because of abandonment—the quiet, systematic abandonment of governance, reform, cohesion, and duty by those entrusted to protect and advance it. Let us speak plainly.The Puntland State administration abandoned democratisation—the long-promised one person, one vote project—without explanation, roadmap, […]

You must be logged in to post a comment.