In a small teashop in Garowe, the capital of Puntland, an intense debate reflects the broader currents of international politics playing out in Somalia. The topic? Turkey’s deepening presence in Somalia and the strategic rivalries involving the UAE, Qatar, the United States, and the specter of rising threats from geopolitical instability in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Somalia, a nation long beset by internal conflict, is now an epicenter of great power competition in the Horn of Africa.

I. Turkey’s Strategic Entry into Somalia

Turkey’s modern engagement with Somalia began in earnest in 2011, when then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Mogadishu at the height of a famine crisis. His visit was the first by a non-African leader in over two decades and marked a significant shift in Turkey’s foreign policy — a blend of humanitarian outreach, religious solidarity, and strategic ambition. Ankara launched a range of humanitarian and development initiatives, from building hospitals and roads to opening its largest embassy in Mogadishu.

But what started as humanitarian support quickly evolved into a robust, long-term strategic presence:

Military cooperation: In 2017, Turkey opened Camp TURKSOM in Mogadishu, one of its largest overseas military bases. The facility trains Somali National Army (SNA) units, helping shape a Turkish-aligned military core within Somalia.

Economic investment: Turkish companies control key infrastructure, including Mogadishu’s main port and airport. They have also been active in construction, energy, and education sectors.

Diplomatic leverage: Turkey has positioned itself as a key external actor in Somalia’s politics, often bypassing traditional Western donors and institutions.

II. Centralization vs Federalism: The Critique of Turkey’s Policy

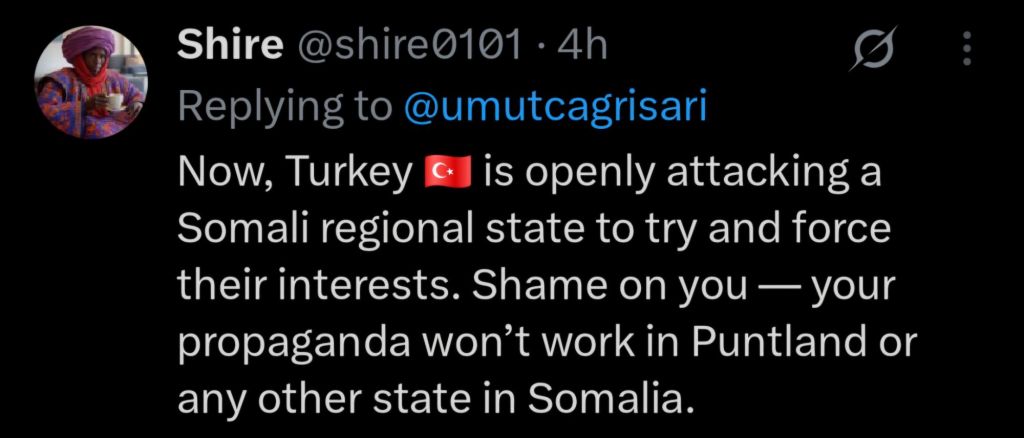

One of the central critiques emerging from within Somalia — echoed in the Garowe debate — is Turkey’s over-reliance on Mogadishu’s central government. This approach, critics argue, ignores the realities of Somalia’s federal structure, where semi-autonomous member states like Puntland, Jubaland, and Galmudug wield significant power and territorial control.

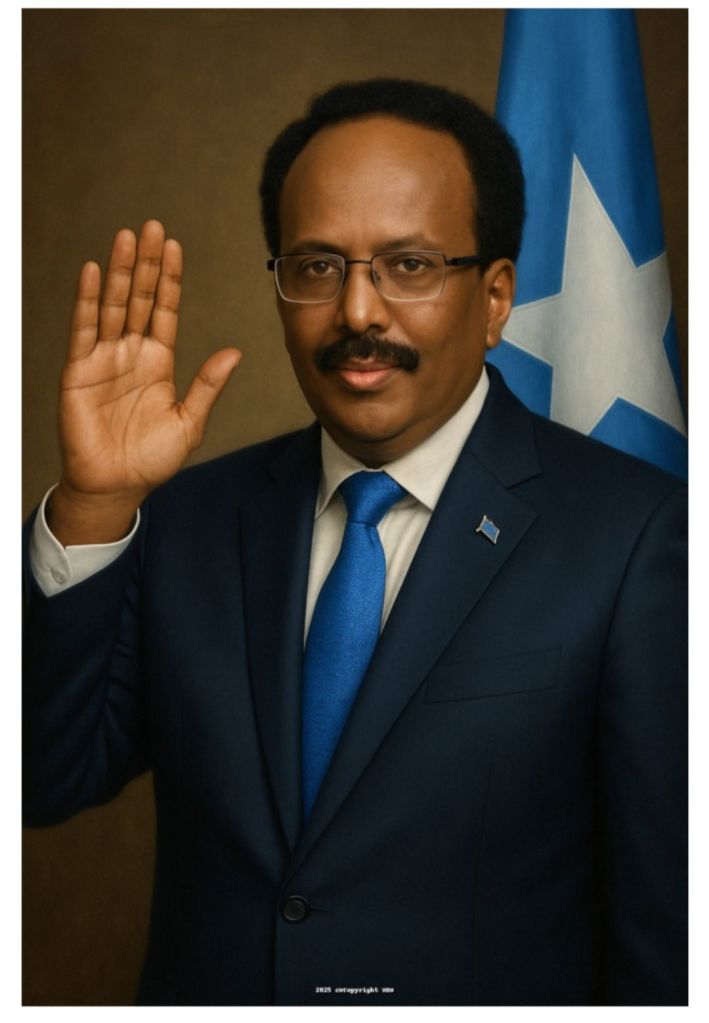

Turkey’s preference for working exclusively with the federal government has created friction with federal member states. These entities often view Ankara’s approach as undermining Somalia’s federal model and centralizing power in Mogadishu, a city with tenuous control beyond its immediate surroundings. Turkey’s alignment with weak or embattled central governments, as seen during the Farmaajo administration, has further exacerbated distrust in regions like Puntland, where political independence and territorial autonomy are zealously guarded.

III. Turkey’s Enduring Footprint and Realpolitik

Despite critiques, another view — espoused in the same debate — argues that Turkey has already cemented a near-permanent presence in Somalia. Its deep institutional ties, military base, and control over revenue-generating infrastructure mean that even if the federal government collapses or is replaced by another force, including Al-Shabaab, Turkey is likely to retain its foothold.

This perspective reflects a realist understanding of foreign policy: Turkey is in Somalia not merely as a humanitarian actor but as a geopolitical competitor seeking influence in a strategic maritime corridor. Somalia offers Turkey a base on the western flank of the Indian Ocean, adjacent to the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, one of the world’s most critical shipping chokepoints.

IV. The Gulf Rivalry: UAE, Qatar, and the Shadow of Proxy Politics

Turkey’s position in Somalia cannot be understood without examining the fierce geopolitical rivalry playing out between Turkey-Qatar on one side and the UAE-Saudi Arabia on the other.

UAE’s strategy: The UAE has pursued a “federal-first” strategy, cultivating ties with Puntland and Somaliland, where it has built the Berbera port and military facilities. Abu Dhabi views Turkish and Qatari influence in Mogadishu as a threat to its broader Red Sea and Indian Ocean strategy.

Qatar’s alignment: Doha, often aligned with Turkey, has funded political actors in Mogadishu and has supported Islamist-leaning political movements such as Damul Jadiid — a factor that aligns poorly with UAE’s secular authoritarian model.

The result is a complex web of local and regional alliances, with Somali factions often serving as proxies for competing Gulf powers. The rivalry spills into domestic politics, clan dynamics, and even armed conflicts.

V. The United States and the Resource Factor

Adding another layer is the role of the United States. Although historically supportive of Somalia’s federal government, Washington has become increasingly wary of foreign actors such as Turkey, China, and the Gulf states entrenching themselves in Somalia’s institutions and infrastructure. Of particular concern is the potential exploitation of untapped offshore hydrocarbons — believed to exist in Somalia’s Indian Ocean waters.

U.S. officials are especially cautious of Turkey gaining exclusive energy rights in Somalia, particularly in light of Ankara’s assertive energy policies in the Eastern Mediterranean. American interests also include counterterrorism, maritime security, and preventing Chinese or Russian encroachment in this strategic corridor.

VI. The Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and the Bigger Chessboard

Beyond Somalia itself, the Horn of Africa is embedded in a larger geopolitical theater. The Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden are now areas of intense interest due to:

Increased naval traffic and global trade routes.

The militarization of strategic ports (Djibouti, Berbera, Assab).

Rising Houthi-Iranian influence in Yemen, directly across the water from Somalia.

New military alliances, such as the Red Sea Council (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, etc.), seeking to control maritime routes and exclude rival powers like Turkey and Iran.

Somalia’s long coastline — the longest in mainland Africa — makes it a pivotal node in this maritime network. Any power with influence in Somalia has a say in broader Indian Ocean geopolitics.

VII. Conclusion: Somalia as a Geopolitical Battleground

The debate in the Garowe teashop captures a microcosm of a larger truth: Somalia, once seen solely through the lens of state failure and humanitarian crisis, is now a stage for global strategic competition. Turkey’s presence is deep and likely enduring, but it is also challenged by Emirati pragmatism, Qatari alliances, American caution, and Somali federal complexity.

In the years to come, the key questions will be:

Can Somalia navigate these external rivalries without becoming a client state of any particular axis?

Will Turkey broaden its engagement beyond Mogadishu to federal states like Puntland, or continue to alienate regional power centers?

How will hydrocarbons, port politics, and military rivalries reshape Somali sovereignty?

Somalia’s future lies not just in peace-building and governance reform but in managing its geography — a blessing and a curse in the current world order.

You must be logged in to post a comment.