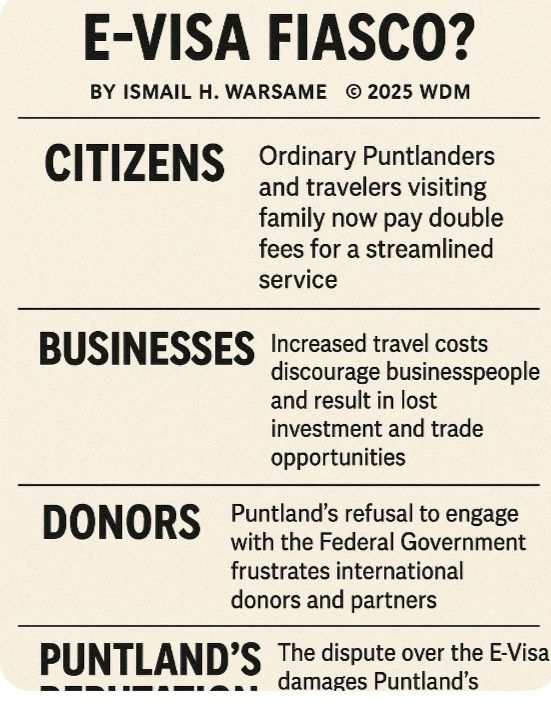

Ismail H Warsame Warsame Digital Media (WDM) September 21, 2025

Abstract

While international counter-terrorism discourse concerning Somalia has predominantly focused on the Federal Government in Mogadishu and the threat of al-Shabaab in the south, the semi-autonomous state of Puntland has conducted a sustained, iterative counter-insurgency (COIN) campaign in its northern territories for over three decades. This article argues that through a process of tactical adaptation and strategic learning, Puntland has developed an effective, locally-led doctrine focused on severing the logistical connection between vulnerable port settlements and mountainous insurgent sanctuaries. By analyzing five distinct conflict phases from the rise of Al-Itihaad al-Islami (AIAI) to the recent offensive against Islamic State affiliates in the Cal Miskaad range, this study demonstrates how regional authorities can develop a sustainable capacity to degrade transnational terrorist cells. This history, often overlooked due to its remote theater and fragmented documentation, offers a significant case study in the primacy of terrain and logistics in asymmetric warfare. The analysis draws on United Nations monitoring reports, historical studies, and the firsthand accounts of local officials like Ismail H. Warsame to articulate a coherent narrative of Puntland’s strategic evolution.

Keywords: Somalia, Puntland, Counter-Insurgency, Al-Shabaab, Islamic State, Terrorism, Horn of Africa, Logistics, Regional Security

—

Introduction: The Littoral-Highland Battlespace

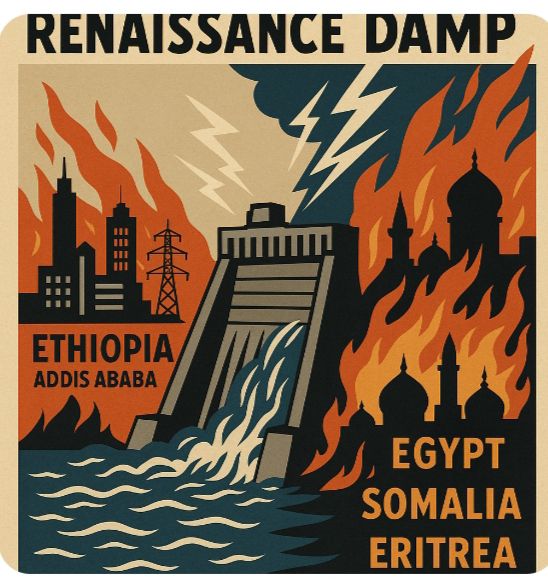

The strategic geography of Northern Somalia presents a quintessential challenge for counter-insurgency (COIN). The rugged Cal Miskaad and Golis mountain ranges, with their complex systems of caves and wadis, offer natural sanctuary for non-state actors.[^1] This terrain is juxtaposed with a long, porous coastline dotted with isolated villages and inlets, providing critical access points for personnel and material. The persistent objective for a succession of jihadist groups has been to fuse these two domains—mountain sanctuary and littoral logistics—into a durable operational base.[^2]

Despite the strategic significance of this region, the sustained conflict within Puntland’s borders has received scant scholarly attention compared to the upheavals in South-Central Somalia. This gap in the literature exists because much of Puntland’s conflict has unfolded in inaccessible terrain, was reported in scattered field dispatches and monitoring group memos, and was often overshadowed by concurrent political crises in Mogadishu.[^3] This article synthesizes these fragmented sources to construct a coherent historical narrative. It posits that through a process of iterative learning across three decades, Puntland’s security forces have evolved from reliant on ad-hoc militias to a professionalized, integrated command structure capable of executing a sophisticated COIN doctrine. This doctrine, culminating in the 2024-25 Cal Miskaad offensive, is predicated on a single, consistent strategic imperative: control the coastline to isolate the highlands, thereby rendering terrain-based sanctuaries unsustainable.

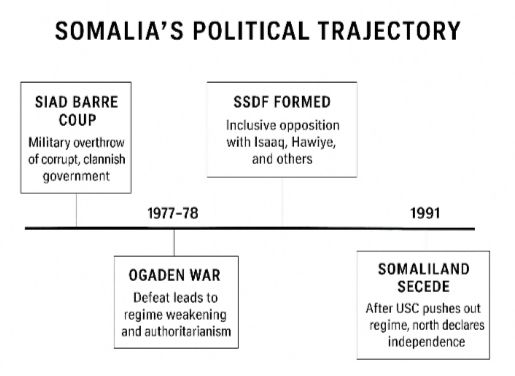

The Precedent: Al-Itihaad al-Islami and the Foundational Lessons (Early–Mid 1990s)

Before “counter-terrorism” became a pillar of international engagement with Somalia, Puntland’s founding authorities faced their first organized Islamist challenge. In the early 1990s, Al-Itihaad al-Islami (AIAI), then the most coherent Islamist formation in the country, briefly established a governance project in the major port city of Bosaso.[^4] AIAI sought to impose its Sharia-first system as warlordism raged elsewhere, effectively using the port as a source of revenue and legitimacy.

This experiment was short-lived. SSDF-aligned forces, representing Puntland’s nascent governing authority, rolled back AIAI’s control in the north, while a devastating Ethiopian military intervention smashed its rear bases around Luuq and in the Ogaden corridor.[^5] This initial episode was formative. It imparted two enduring lessons that would echo through subsequent conflicts: first, port cities are high-value strategic prizes whose control is essential for any group seeking sustained operations; and second, the northern mountain ranges, while not the primary front in this early episode, were recognized as potential sanctuaries and force-multipliers. The response also set a precedent for cooperation with external actors, namely Ethiopia, which has remained a recurring feature of Puntland’s security strategy.[^6]

Phase I: The Islamic Courts Union and the Battle of Bandiradley (December 2006)

The rise of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) in 2006 and its rapid territorial expansion presented a direct conventional threat to Puntland. In late 2006, ICU forces surged northward, with the strategic town of Bandiradley becoming the forward pressure point. The battle for Bandiradley was a short, sharp engagement. Puntland forces, operating in concert with militias from Galmudug and with critical support from Ethiopian units, broke the ICU’s line and pushed it south.[^7]

Strategically, the victory at Bandiradley halted an Islamist pincer movement aimed at Galkayo—a key economic hub—and the artery of the Bari road.[^8] It served as a blocking action, buying Puntland crucial time to harden its internal defenses and consolidate its territorial control. This phase demonstrated Puntland’s initial capacity to integrate external military support and local militias to defeat a conventional advance, reinforcing the lesson that the mountain passes were critical terrain that must be denied to an invading force.

Phase II: The Galgala Insurgency and Attritional Warfare (2009–2011)

Following the conventional defeat of the ICU, the conflict evolved into a protracted insurgency. A former AIAI member, Mohamed Said “Atom,” nested cells and ambush teams within the limestone folds of the Galgala-Calmadow range.[^9] Atom claimed affiliation with al-Shabaab, which was now the dominant jihadist force in the south, operating with a degree of autonomy as a franchise.[^10]

Puntland’s counter-insurgency response became attritional. The Puntland Security Force (PSF), a more professionalized unit, led raids and conducted painstaking ridge-to-ridge clearances. The critical strategic effort, however, was the gradual isolation of Atom’s supply lines extending to the coast.[^11] By late 2010 and into 2011, the hills remained contested but Atom’s cadre had been bled dry and scattered. The Galgala campaign proved a vital lesson: mountainous terrain offers immense advantages to guerrillas, but only if they can maintain a steady flow of logistics. A strategy of littoral denial could starve a mountain-based insurgency.

Phase III & IV: Littoral Maneuver and Jihadist Fracture (2016)

The year 2016 witnessed a tactical shift by insurgents and a fracturing of the jihadist landscape, testing Puntland’s adaptive capacity.

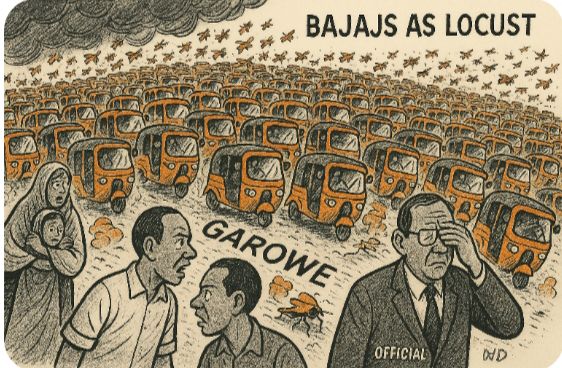

In March, al-Shabaab executed a strategic pivot towards littoral warfare. Fighters landed by boat and overran the small port of Gara’ad (Garacad), briefly opening a second front while operations in Galgala continued.[^12] Puntland forces counter-attacked within days and restored control, but the message was unambiguous: the coastline was a critical vulnerability, and any unpoliced cove could be transformed into a staging point.[^13]

Later that same year, a new threat emerged. An ISIS-aligned splinter faction led by ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min seized the coastal town of Qandala, hoisting its flag for several weeks before being ejected.[^14] This event had significant implications. Puntland now faced two distinct jihadist brands—al-Shabaab and ISIS-Somalia—competing for the same strategic space. The response demonstrated Puntland’s growing sophistication; it learned to contain both groups simultaneously and, crucially, to deny either a permanent port facility, adhering to the core principle of its emerging doctrine.

Phase V: The Cal Miskaad Offensive and Doctrine Culmination (2024–2025)

The most recent and large-scale operation represents the maturation of the Puntland Doctrine. In a coordinated multi-service offensive, units from the PSF, Darawish, PMPF, and police surged into the Cal Miskaad range to dismantle the strongholds of ISIS-Somalia.[^15] This campaign was notable for its integration of external enablers, who provided precision strike capabilities, alongside highly mobile local forces with superior knowledge of the terrain. The operation rolled up base clusters, reopened key tracks, and provoked a costly, mass-casualty counterattack by ISIS on December 31, 2024—a sign of the pressure applied. By early 2025, officials reported dozens of sites cleared and significant territory retaken.[^16]

The Cal Miskaad offensive was not merely a tactical victory. It was the culmination of a doctrine hammered out over three decades: treat the littoral-mountain system as an integrated battlespace, close the coves, and starve the hills. It also carried a potent political message: regional forces, with targeted external support, can effectively degrade transnational terrorist cells without waiting on a centralized national command from Mogadishu.[^17] This aligns with the long-standing principle of self-reliance chronicled by local observers of Puntland’s political development.[^18]

Analysis: The Through-Lines of a Doctrine

Synthesizing these five conflicts reveals the consistent pillars of Puntland’s strategic approach:

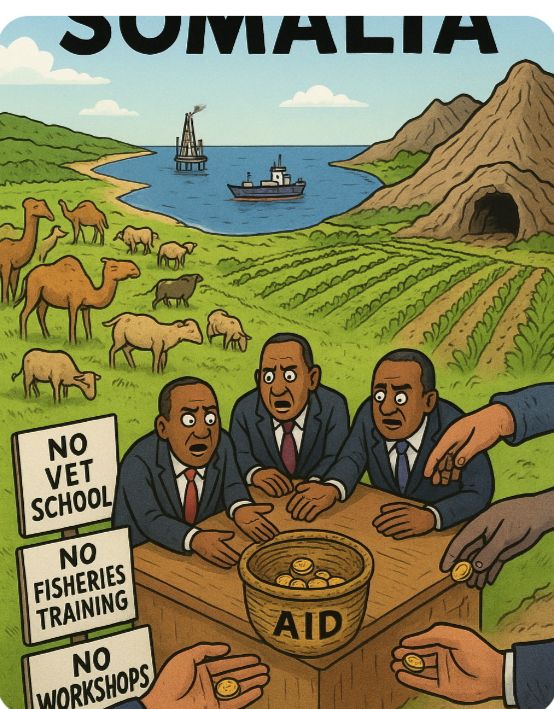

1. The Primacy of Logistics over Terrain: Every militant surge, from AIAI to ISIS, targeted a port or coastal landing point. Puntland’s strategy correctly identified that controlling terrain is secondary to controlling its sustenance. A mountain sanctuary is worthless without a pipeline of resources.[^19]

2. Adaptive Learning: Puntland’s command structure evolved iteratively in response to new threats. Its forces transformed from ad-hoc militias to a specialized PSF, and finally to an integrated command capable of coordinating multiple units and leveraging external precision support. This organizational learning curve proved steeper than the tactical adaptations of its adversaries.

3. The Efficacy of Regional Initiative: The consistent success factor was local leadership and knowledge. Forces from Puntland, with an intimate understanding of the human and physical geography, proved to be the most effective instrument for COIN in this complex environment. This aligns with the observations of insiders like Ismail H. Warsame, who has chronicled Puntland’s institution-building and its strategic principle of self-reliance in security matters.[^20] The model of local lead with targeted, enabling external help has been the only one to consistently achieve tactical and strategic effects.

Conclusion

The history of conflict in Puntland is not a series of disconnected skirmishes but a continuous, thirty-year arc of strategic learning. The “Puntland Doctrine” that emerged is a pragmatic, terrain-specific approach to counter-insurgency that understands the critical link between logistics and sanctuary. As articulated by local figures like Warsame, this doctrine is rooted in a pragmatic assessment of local needs rather than abstract theories imposed from outside.[^21] The 2024-25 campaign in the Cal Miskaad mountains is not an isolated event but the logical endpoint of a strategy refined since AIAI first tested the defenses of northern ports.

This case study offers broader lessons for security studies and COIN theory. It underscores that effective counter-insurgency often depends on granular, local knowledge and regional initiative rather than solely on centralized national strategies. It also reaffirms the timeless military axiom that logistics, not just terrain, dictate the viability of an insurgency. For policymakers, the Puntland case argues for a model of security cooperation that empowers capable local actors with the precise support they need, rather than imposing top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions. The untold story of Puntland’s long defense of its ridgelines and coastline is, ultimately, a story of strategic adaptation and the enduring importance of controlling the means of sustenance in war.

—

Notes

[^1]: Ken Menkhaus, Somalia: State Collapse and the Threat of Terrorism (New York: Routledge, 2004), 45-48.

[^2]:United Nations Security Council, Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, S/2017/924 (New York: United Nations, 2017), 12-15.

[^3]:Stig Jarle Hansen, Al-Shabaab in Somalia: The History and Ideology of a Militant Islamist Group (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 112.

[^4]:Matt Bryden, The Rise and Fall of Al-Itihaad al-Islami in Somalia (Nairobi: UNPD Somalia, 1999), 22.

[^5]:Bryden, Rise and Fall, 28-30.

[^6]:United Nations Security Council, Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, S/2010/91 (New York: United Nations, 2010), 51.

[^7]:Hansen, Al-Shabaab in Somalia, 134.

[^8]:United Nations Security Council, S/2010/91, 54.

[^9]:United Nations Security Council, Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, S/2022/822 (New York: United Nations, 2022), 19.

[^10]:Hansen, Al-Shabaab in Somalia, 156.

[^11]:United Nations Security Council, S/2017/924, 21.

[^12]:United Nations Security Council, S/2017/924, 34.

[^13]:United Nations Security Council, S/2017/924, 35.

[^14]:United Nations Security Council, S/2017/924, 38-40.

[^15]:United Nations Security Council, S/2022/822, 25.

[^16]:United Nations Security Council, S/2022/822, 27-29.

[^17]:Ismail H. Warsame, “Puntland’s Strategy Against Terrorist Groups,” WardheerNews, October 15, 2016, https://wardheernews.com/puntlands-strategy-terrorist-groups/.

[^18]:Ismail H. Warsame, “The Genesis of Puntland State of Somalia,” (self-published monograph, 2018), 45.

[^19]:Menkhaus, State Collapse, 72.

[^20]:Warsame, “Puntland’s Strategy Against Terrorist Groups.”

[^21]:Warsame, “The Genesis of Puntland State of Somalia,” 102.

—

Bibliography

Bryden, Matt. The Rise and Fall of Al-Itihaad al-Islami in Somalia. Nairobi: UNPD Somalia, 1999.

Hansen, Stig Jarle. Al-Shabaab in Somalia: The History and Ideology of a Militant Islamist Group. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Menkhaus, Ken. Somalia: State Collapse and the Threat of Terrorism. New York: Routledge, 2004.

United Nations Security Council. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. S/2010/91. New York: United Nations, 2010.

———. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. S/2017/924. New York: United Nations, 2017.

———. Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. S/2022/822. New York: United Nations, 2022.

Warsame, Ismail H. “Puntland’s Strategy Against Terrorist Groups.” WardheerNews, October 15, 2016. https://wardheernews.com/puntlands-strategy-terrorist-groups/.

———. “The Genesis of Puntland State of Somalia.” Self-published monograph, 2018.

You must be logged in to post a comment.