| Source: SOMALIA WATCH |

| By Federico Battera, Saturday, August 12, 2000 UNDOS Research Specialist, Professor Development Studies – University of Trieste, Italy Summary and purposes The crisis of the State in Africa goes back to the early 80s: postcolonial African state has been neither able ‘to rule’ economy, nor territorial policy. Ethnicity has spread all over the continent. However, after the failure of the consociative policies channeled through one-party systems, the most evident factor has been its territorial dimension. Since the middle of the 80s, as the State machine has been evidently unable to expand, politicization has taken over territory, giving ethnicity a new relevance as to contrast territorial legitimacy, which had been acquired by the State through the decolonization process.Somalia has not escaped the trend, sliding into a civil war since the beginning of the 80s. By early 90s it has become the paradigmatic example of the failure of the state. Centralization, as conceived by the collapsed regime, turned into a non-state existence, distinguished by independent areas controlled by different ‘fronts’ or ‘movements’ drawn up along clan lines. By mid 90s the situation improved in certain areas and stabilized in others. A de facto regionalization has gone out: since then, some areas has progressed to a ‘recovery’ condition, other has been classified by UN as ‘transition’ zones or ‘crisis’ zones, the latter characterized by a steadfast state of ravage and insecurity.The crisis of the State in Africa has generated in major cases conditions of democratic change. Constitutional processes has been the consequence of the change. Almost everywhere, it has been the output of a widely expressed need of strengthening democratic procedures. Only in few cases, the issue of territorial dimension of ethnicity has been addressed through strict federalist guidelines (as tried to do Ethiopia), but decentralization and devolution has remained the major question on the ground, together with democracy.’Recovery’ areas in Somalia (mainly Northwest and Northeast Somalia) around mid 90s gained momentum, as the situation in the rest of the country remained critical. Since then, new local conditions in the North have granted security and a certain stability, besides their differences. In 1991, the liberation struggle from Barre’s regime in Northwest Somalia ended with the declaration of independence of Somaliland. The constitutional process was the unavoidable following step. In 1993, a National transitional Charter were approved and accepted by all the communities in the region, giving full legitimization at the process. In 1997, a new (interim) Constitution were passed out, after a new Constitutional Conference that ended a two-years crisis. After that, Somaliland is waiting its international recognition.The constitutional process in Northeast Somalia has started later. As has been rightly stated by Farah, better conditions of peace and recovery do not necessarily lead to a climate favorable to a new institutional framework. Besides, Northeast Somalia did not share the same eagerness of Somaliland to acquire independence. Nevertheless, a constitutional process has started since the end of 1997. The aim of this paper is to outline the constitutional process and the main characteristics of the Charter approved and secondly to draw up the political effects of the new process on Somalia. After all, a new political entity has been originated from Somali disorder.As what concern the first point, the Charter, comparing to the Draft, stresses the Islamic identity of the new entity and its presidential biases. Regarding the political effects of the birth of the new regional state, it is personal opinion of the author that it will affect the entire reconciliation process in Somalia and, in a certain extent, the stability of Somaliland. Comparing to Somaliland, the territorial dimension of the new entity is openly averted. One reason is that a request for an international recognition is not on the agenda. However, an alternative explanation resides on the clan structure of the new state. Contrary to Somaliland, clan agreement has preceded any territorial definition. So far, Puntland has yet to be clearly defined on the map, a part the vague identification with Northeast Somalia. As we will see, important issues like that of decentralization of the state have not been avoided only with the intent of endorsing with more power the new political leadership (as trying to avoid the same fate of the country) but because of the naturally decentralized structure of Somali society. Seems like that the manifest ambiguities of the Charter has been provided in order to leave the door open for different future solutions. Indeed, the Charter is only provisional. Further alterations have not to be excluded, depending on internal and international conditions. As Somaliland, seven years later the first National Charter still in the middle of its constitutional process, Puntland might not easily finalized its one. The process, the participation degree and the informal institutional constraints that has been settled during the whole period more than its final document is the mirror of the vitality of the involved society. Focusing on it is not a vain academic exercise.The author had the opportunity to follow the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which with the assistance of foreign consultants drafted the Charter that was later submitted to the Constitutional Conference. Comparing the Draft with the final Charter has been the main source of the paper. Such a method elucidates the needs and the expectations of the members of the Constitutional Conference in charged with its approval. Such a source has been compared to local sources as well as previous reports.BackgroundFollowing the pattern of the Booroma National Charter, which formalized the birth of Somaliland during 1993, a new entity – the Puntland State of Somalia – was established in July 1998 out of a long Constitutional process that lasted more than two months. As in Boorama, the Constitutional Conference produced a three-year provisional Charter and elected a political leadership, i. e. a President and an Executive Council (called Council of Ministers in the Boorama Charter).Boorama paved the way, but it is a fact that the Puntland Constitutional Conference has been the product of a longer process, which officially started during 1997 but went back to the second National Reconciliation Conference of Addis Ababa of 1993. Indeed, during the National Reconciliation Conference, the SSDF (Somali Salvation Democratic Front) leadership anticipated its ‘federalist’ view of the future of Somalia, unofficially disclosed during 1994 in a statement by the Somali Community Information Centre in London. During the last five years, the federalist position has gradually acquired substance, recognizing the de facto situation on the ground: a clan-divided Somalia. Finally, the failure of several national reconciliation processes, from Sodere (1996) to Cairo (1997), created the condition for an autonomous regional process, pending the formation of other regional entities and the establishment of a new Federal Somalia.The Features of the CharterThe Charter, however transitory, defines a presidential system with a President able to dismiss the unicameral Parliament or House of Representatives (see Art. 12.5 of attached Charter). The House of Representatives consists of 69 members, representing of all constituent regions (Art. 8). However, an other chamber (of elders) has been proposed, called the Isimada (Art. 30) whose constitutional powers are not clear but would ostensibly need to be defined by the future Constitution.Even though, the Isimada could play a significant role, since the Charter formally recognizes to it a role of mediation between institutions (both State and regions and districts), in case of stalemate or disputes among “the community” (i. e. Puntland community as well a single clan) (see Art. 30.2): power that, together with that of selecting the members of the House of Representatives (30.3), gives it potentially an important role. The selection of the members has been carried out thanks to a careful balance between the numerical relevance of all communities and their number, to avert the exclusion of any political minority. Hence, this was an indirect election, without direct competition between parties and candidates. This required long debates among the communities involved; debates characterized by opposing vetoes between and among the communities followed by the selection of suitable candidates. Being the local community the natural constituency, it has been a consequence that only the elders played a role, as stated by the Charter itself (see, Art. 8.6).Although the selection seems to have relied on territorial criteria, it closely follows more an ‘a-territorial’ and consociative model. Such a criteria has already settled on the issue of the ministerial posts as well of the departments, agencies, judiciary agencies etc. So far, these are the de facto base of the forthcoming decentralization of the State (Art. 1.8), waiting for the matter to be regulated by law (Art. 18.1). Meanwhile, the State, and the Executive in particular, will nominate the governors of the regions and the mayors of districts, but always after direct consultation with district elders (Art. 18.3). The matter of decentralization is particularly delicate because one of the reasons for the collapse of Somalia was the unbalanced relation between the political center and periphery. In this sense, the Charter is still unclear and vague. What is evident is that the Charter does not recognize any formal function to the District Councils (DCs) and definitely removes any pre-exisiting regional community council (Art. 9.5).The matter shall be resolved in the future by the Executive.Besides the legislative one, the House of Representatives has other important responsabilities (see Art. 10.3): the approval and the rejection of ministerial nominees proposed by the President, the ratification or rejection of agreements and negotiations to achieve a federal national solution with other regional entities, and of all the future proposals submitted by the Executive concerning decentralization. Moreover, the Charter bestows the power to remove the immunity of the President on the House of Representatives (the so-called impeachment; Art. 14.1) upon a two-thirds majority vote. The procedure must be submitted to the House by the Executive-nominated (but House-approved) Attorney General.The Judiciary must be independent of both the Executive and the Legislative (Art. 19.1). Three levels of proceedings have been put in force (Primary Courts, Courts of Appeal and Supreme Court) (Art. 19.2), but the Charter recognizes, encourages and supports “alternative dispute resolution” (Art. 25.4) in keeping with the traditional culture of Puntland. Therefore, the State directly recognizes the force of the xeer (the customary law), that so far has held more sway than penal codes in the region.Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is the “basis” of law (Arts. 2 and 19.1). An implicit recognition of the superiority of ?ari‘a law exists, even though the lawmakers have preferred to avoid the more mandatory “the only source” of law, as in other juridical contexts. This is an ambiguous formula aiming to both recognize the ongoing regional process of re-Islamization as well as defuse its excessive aspects. Therefore, the Charter continually emphasizes the values of Islam, the State religion (Art. 2). The President himself must be a practicing Muslim (Art. 12.3), a quality not required for the members of the House (Art. 9). The Constitutional Court, which shall come into force with the future Constitution, is entrusted with all the issues and conflicts that might arise between Islamic jurisprudence and the law of the State and the Constitution itself (Art. 21.5). This conformity to Islamic values and the general reference of the Charter to the Islamic identity of Puntland is, moreover, stressed by the good relations that, pending the creation of Federal Somalia, Puntland is willing to maintain with the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) (Art. 5.3), which the original Draft did not mention.The general stress on the Islamic identity is confirmed in the chapter on the fundamental rights and freedom (Art. 6). On this point, the Charter introduces the widest changes in respect to the Draft. The Charter recognizes the freedom of thought and conscience, but forbids any religious propaganda other than Islam (Art. 6.2). This was one of the more discussed issues, during the meetings of the Preparatory Committee, which introduced the Draft to the Conference. In its approved version, the Draft made no reference to such a prohibition. In Article 6.2.1, the Draft explicitly recognized other religious denominations without the limitations introduced later by the Charter, which prefers to consider other creeds as “freedom of thought and conscience“. So clarified, the prohibition of other religious propaganda is not intended to limit a fundamental right of thought, which is per se unlimitable. It is a fact, that almost all the future Puntland citizens are, practicing or not, Muslims. Such statements are probably intended to define more precisely the religious identity of the State, especially in respect to the outside Islamic world, in particular after allegations that Ethiopia stand behind the constitutional process had been spread in the country.Contrary to the Draft, the Charter necessitates the adoption of regulation of freedom of expression. Article 6.3 contains the prohibition of torture unless the person is sentenced by courts in accordance with Islamic law. This is an indirect admission of the legality of corporal punishments. Such punishment is admitted by Islamic law (as hudud) but not by Somali customary law (xeer). Defining this punishment as “torture” contradicts the new State’s (not the Charter) acceptance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Art. 5.2). This evident contradiction has been obviously only a problem of lack of understanding between different linguistic versions. The Draft, originally written in English, strongly forbids torture (Art. 6.3) and any other degrading treatment – “no one shall be subjected to torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment…“. The English version of the approved Charter cuts the sentence relating to the degrading treatment, introducing a misleading distinction between torture and Islamic (corporal) punishments – “no one shall be subjected to torture unless sentenced by the Islamic Courts“. This distinction is more evident in the Somali version of the Charter, with the word jir-dil (lit. “body-beaten”) replacing “torture” openly referring to corporal punishments.It is worth noticing that the Charter explicitly introduces a specific citizenship (Art. 1.11), regulated by law, but recognizing from now on the right of every Somali citizen, who respects the Charter and the law, to reside in Puntland and conduct any economic activity (Art. 1.5). The issue of citizenship was intentionally avoided by the Draft which preferred formulas as “the people of Puntland will accept only those limitations on their sovereignty that may arise from their obligations as citizens of a democratic Federal Somalia” (Art. 1.5 of the Draft)”. Moreover, the Charter, at the Article 1.9, cut the word “Democratic” from that of the Draft, preferring to label Somalia simply “Federal” (Art. 1.9). This thought-provoking omission (almost all present constitutional systems define themselves as ‘democratic’) probably should be understood as the product of the strong will to adhere to a re-established Somalia only at particular conditions leaving open other options, but saving the federal formula. In other words the present Charter is intended to give precise limitations to those who should participate in the name of Puntland in a constitutional process at the national level, affecting the agenda of future reconciliation processes.As far as this delicate point of the cession of sovereignty is concerned, the Draft introduced as Annex 1 (Powers and Functions that Puntland is willing to transfer to or share with the Federal Government of a democratic Federal Somalia) a fine distinction between transferable functions and shareable functions. The former is defined as functions exclusively belonging to the Federal Government, (mainly, the regulation of currency and Foreign affairs), and the latter as those belonging to the states, (the regulation of the seas and the airspace of Somalia, national defense, the determination of customs fees and the management of the Federal Bank). Of all these regulations remains scant in the final Charter apart from a reference in Article 1.6. This article leaves, in a very vague way, to the dialogue between states or between Puntland state and the Central government, after the approval of the House of Representatives (Art. 10.3), what will be transferred to the future Central Federal Government. Hence, Puntland is part of Somalia, and it is striving to recreate the unity of Somali people (Art. 1.4), but the modalities of realization remain only an option still to be negotiated. So far, in fact, Puntland has not advanced any international recognition.The effects of the birth of Puntland on the process of reconciliation and fragmentation in SomaliaAt a first glance, the Charter outlines the structure of the government as the Draft does, but more unbalanced to the presidency. First, the President has the power to dismiss the House of Representatives (Art. 12.5, h), a power the Draft did not grant. Second, the State of Emergency (Art. 12.5, l), limited by the Draft to six months, is totally unlimited in the Charter. The choice of the name of the chief of the Executive itself (President) instead of Chief Minister, as proposed in the Draft, comes from the need to ensure a stronger Executive, as was so clear during the long discussions within the Preparatory Committee. Most likely, the Preparatory Committee intended to reserve this title for the Federal Executive. Therefore, the House has no way to dismiss the Executive – but the same occurred in the Draft – except for the impeachment (requiring upon a two-thirds majority) and the rejection of other ministerial nominees (Art. 10.3, d).The Constitutional Conference itself empowered the President for a three-year transitional period. Cabdullahi Yuusuf, a prominent military and political leader of the now dissolved SSDF, was elected with more than 80% of the votes (377) cast out of the 469 members of the Community Constitutional Conference. This gives him a free hand for his three-year term of office, as is the case for other Arab and African presidential systems. Nevertheless, without any formal strong check and balance, the Executive does face an “informal” balance in the strong political autonomy of the traditional leaderships (isimo). Indeed, the Charter recognizes their crucial mediation functions (Arts. 30, 8 and 18); among the most important of them is the role of selecting the representatives. Differently from the Guurti of Somaliland, in this case the Isimo have preferred to renounce more defined roles that would have restricted their exercise of authority, preferring to maintain an uninstitutionalized ‘gray zone’ where they could intervene without any defined restriction and with much more flexibility in order to achieve a more widespread political consensus. It remains to be seen whether those recognized powers will remain in place in the more complex and complete Constitution to come, at the end of the transitional process.This unceasing search for the widest political consensus over issues and this concern about unanimity, manifested during the Constitutional Conference (which went far beyond the scheduled fifteen days) show how a political tradition both resists and adapts itself to modern politics. Freedom of association, including the right to form political parties, however admitted (Art. 6.2, b), is de facto bypassed by a non-party system, where different positions over issues are channeled through clan networks and interest groups (economic, regional, religious and family groups). That does not mean that opposition and disputes are definitively overcome, but that these are rather voiced through interest groups.The formation of Puntland itself is the result of an intercommunity agreement between all Harti (Majeerteen + Dhulbahante + Warsangeli) communities of the North. Is a matter of concern that this agreement should start a border conflict with the neighboring countries or the others de facto entities. Indeed, the Article 1. of the Charter establishes the borders along the former regions and districts which comprise a Harti majority: Bari, Nugaal, Sool, southern Togdheer (Buuhoodle district), Mudug (with the exception of Hobyo and Xarardheere districts) and Southern, Eastern and North-Eastern Sanaag. So defined, the Puntland State of Somalia claims sovereignty over territories that constitute part of Somaliland (Sanaag, Sool and Togdheer).That these regions and districts constitute parts of Somaliland may be matter of future conflicts between the two states. The communities of these districts did not completely take part in the first constituent congress (shir beeleed) of 1991 in Burco which declared independence, but did participate in the 1993 congress in Boorama which drew up the first Charter of Somaliland. Moreover, Somaliland, since the 1991 declaration, is in search of an international recognition relying on the legal basis of its previous short independence (only five days) before it merged with the former Italian Trusteeship Territory of Somalia in 1960.The creation of Puntland State of Somalia has, indeed, created a stalemate between the two entities. Fortunately, it has not so far deteriorated to a military conflict, maybe thanks to the Ethiopian political mediation between the two. The geographical proximity and the economic dependence on Ethiopia, together with the open hostility of Egypt and the Arab League towards the independence process in Somaliland lead to unalignment of the political position of Somaliland to that of Ethiopia.At the present, the government of Somaliland is, indeed, unable to exert a direct rule over its eastern part, which has largely joined Puntland. Maxmuud Fagadheh, a Dhulbahante from Eastern Somaliland, Foreign Affairs minister of the Cigaal government, is still in the government of Somaliland. In the meantime, 213 delegates out of the 469 to be present at the Constitutional Conference of Puntland came from Eastern Somaliland. Sool and Sanaag sent 27 of the 69 representatives to the Parliament of Puntland. Maxamed Cabdi Xaashi, the former leader of dismissed USP, the leading political and military faction in Eastern Somaliland, has been elected to the Vice-Presidency of Puntland, and three of the nine cabinet ministers of Puntland come from the contested regions. Moreover, an official statement of Harti traditional leaders (Isimo) of Eastern Somaliland associated themselves with the process of formation of Puntland and, so doing, legitimized this process, although the Isimo themselves are fully entitled to be part of the Guurti (the Senate of elders of Somaliland). In other words, Eastern Somaliland might become a buffer zone between the two entities, without clearly defined sovereignty.One of the first effects of the formation of Puntland might be that Somaliland government gives up its claim of independence. In this perspective, the recent declaration of President Cigaal in favor of a confederation system for a united Somalia, after his February journey in Egypt makes sense. A more long-term effect should be the proliferation of other new regional entities as the product of intercommunity (interclan) agreements. Besides, Puntland itself, as it appears today, could be easily named Hartiland. The Charter itself, in Article 1.2, leaves the door open to further additions to Puntland State, first of all “The community that participated in the Garowe consultancy meeting on February 1998“, the meeting which started the final phase of the constitutional process. This is a clear reference to the Marreexaan of Northern Galgaduud, which withdrew in the last stages of the process. Their further participation could transform Puntland from a Northern Hartiland to a Northern Daaroodland.In this perspective, Somalia should take the form on the ground, which was outlined by the SSDF network document in London 1994: a Federal Somalia founded on five entities corresponding to the five large clan confederations – Dir (Isaaq + Ciise + Gadabuursi) in the northwest, Northern Daarood in the north-east, Hawiye in the middle, Digil and Mirifle in the interiverine area (Bakool e Baay), Southern Daarood in the TransJuba area. A similar process is, indeed, restarting in the interiverine area after the push out of SNA from Baaydhaba by the RRA, with the support of Ethiopian troops. On the contrary, one in Hiiraan, the other in TransJuba had different experiences. In Hiiraan the process started in May 1998. It was led by five ex USC (United Somali Congress)-SNA factions (representing five different Hawiye clans of the region), after their successful ‘secession’ from Caydiid’s movement. This process is still incomplete because it tried to embrace the whole Hawiye clan family. A similar process in the TransJuba region has never started because of the internal conflict between factions, among different Daarood movements and the guri/galti (indigenous/newcomers) conflict. Finally, it was definitively halted by the recent seizure of Kismaayo by the combined forces of SNA and SNF.Among the main hindrances in the spreading of the pattern of regional reconstruction processes are: the pursuit of a centralist and anti-federalist approach by the joint administration of Mogadishu, and in particular by the SNA-Caydiid faction, and the anti-clan and unitary approach of the militant wing of the Islamist movement, based mainly in the Upper Juba region (Gedo) (but now threatened by the Ethiopian army), but with a strong political presence in both Banaadir and Mogadishu. These two factors are, in a certain way, bound together, even if the Islamist movement seems to have dropped its ‘taliban’ strategy of military conquest, after its failures at Boosaaso in 1992 and in the Ogaadeen between 1996 and 1997. This movement now prefer to affect local administrations through its social and juridical programs.Concluding remarks and options for the futureBoth northern regions, Somaliland and Puntland, were largely spared the civil conflict following the dramatic collapse of Barre regime. This fact gives them an undeniable asset in respect to the southern regions for a true implementation of reconciliation process. Even if they have not been completely free of clan strife, the northern regions still preserve strong societal ties. The institutional recognition of the role played by the traditional leadership in Puntland in the seven-year period of peaceful self-government in a stateless situation, has come only at the end of this process. However, the mediation role of the elders has not been so successful in other regions of Somalia for several reasons. Generally speaking, outside the Majeerteen context, Somali society lacks a stable hierarchy of paramount chiefs, and it follows that mediation can achieve only a local dimension. Nevertheless, in the northwestern regions (Somaliland) a regionalist feeling has widely spread in the last thirty years. In this part of Somalia, after the collapse of the State, the elders have collectively expressed this feeling better than the SNM, frequently paralyzed by leadership competition. Such regional affinities may be reached in the interiverine region, which has developed similar regionalist feelings after years of ravaging war and exploitation by the former regime, even if the civil conflict has left room for a confrontation between groups. Similar results are more hard to find in the Shabelle and Juba regions because of the confused societal situation complicated by the civil war and migrations.What is going on in Somalia from a political and constitutional point of view represents a defiance of the territorial principle and roots of international law. There is no doubt that international law is still playing and will play an important role in affecting the future juridical and constitutional framework of local governments, but what we are seeing throughout Somalia (and in other part of Africa) is a re-appropriation of imported institutional formulas by local political (and juridical) tradition. This involved the issue of the transplant of western institutions and their encounter with the so-called ‘informal’ sector, which as a concept has been by now enlarged to embrace not only the economic but the political and juridical dimensions. This issue is beyond the purpose of this paper, but has deep influence on contemporary Somalia.From a territorial point of view, the birth of Puntland not only reopens the whole question of internal borders in Somalia but also weakens the meaning of internal and external borders. They remain (in accordance with international law) and even produce a schizophrenic proliferation of district and sub-district boundaries defining community homelands but, in the meantime, generating the search for alternative and ‘informal’ solutions. This is one of the reasons for the failure or the incomplete success of the formal district governments and the better performances of the more flexible and aterritorial institutions such the guurti and isimo.From this point of view, the problem of sovereignty between Somaliland and Puntland that arises from the participation of Sool and Sanaag in the latter’s constitutional process is simply eluded by the participation of Harti in the parliamentary process and in the government of Somaliland. A similar process is smoothly developing between Puntland and the Somali region of Ethiopia: though not widely known, some Ethiopian Harti representatives sit in the Puntland House of Representatives.Similar problems between regional entities may arise and similar solutions may be found when other regional processes reach a more advanced stage. Hence, the formation of new entities will not necessarily mean conflict, but contested territories should play in the future a buffer role. The local concept of State sovereignty does not naturally match with the rigid concept of State territory. Instead, it should expand in the ‘official’ territory of other countries in a flexible way and wherever members of its community are found. This is exactly one of the options offered to end the conflict and to reconstruct Somalia by the LSE consultant to the European Union during 1995. Today, is effectively put into effect in all Somali regions without respect of internal and external borders. From another point of view, it is a slide back to a legal status of the community group, confirmed by a citizenship which corresponds to kinship. These are new elements of extreme importance to those who are directly or indirectly committed to developing alternative solutions in the African context, split up between State sovereignty and ethnic allegiance. What is advancing in Somalia is a more flexible and a more restricted idea of what the State is and means in Africa (and elsewhere). |

Category: Uncategorized

The Mental Split: Why Some Puntlanders Can’t Hold Puntland and Somalia in the Same Head

WAPMEN EDITORIAL

There is a quiet but corrosive confusion eating away at Puntland society — not a military threat, not a fiscal collapse, but a mental fracture. Many residents have reached a breaking point where they can no longer hold two ideas at once: Puntland and Somalia.

One thinker once asked: “Who can keep two opposing ideas in his head without losing his mind?”

The tragedy in Puntland today is that these ideas are not opposing at all — yet they are treated as mortal enemies.

On one side are those chanting “Puntland! Puntland!” as if Puntland were a besieged secessionist republic. On the other are those chanting “Somalia! Somalia!” as if Puntland were an illegal deviation from a unitary past that no longer exists. Each camp believes the other is committing political heresy. Each is trapped in illusion. And between them lies a society caught in intellectual paralysis.

This is not an ideological debate. It is a failure of civic education.

Puntland Is Not Anti-Somalia — And Somalia Is Not Anti-Puntland

Let us state this plainly, because too many leaders have failed to do so:

Puntland was created to save Somalia, not to escape it.

Federalism — imperfect, messy, and often abused — was designed to reconcile local self-rule with national unity. Puntland is not a substitute for Somalia, nor is Somalia a threat to Puntland’s existence. One is a federal member state, the other a federal republic. This is not rocket science. Yet decades after Puntland’s formation, large segments of the population still do not grasp this basic constitutional reality.

Why?

Because no successive Puntland administration invested seriously in civic education. No sustained effort was made to teach citizens what federalism means, what Puntland’s legal status is, where its powers begin and end, and how Somali unity actually functions in a post-1991 political order.

The result is a vacuum — and vacuums are always filled by slogans, rumors, clan narratives, and emotional politics.

A Civic Brainstorming That Exposed a Deeper Deficit

Appraising yesterday’s civic brainstorming at the Puntland State Presidency — and observing the general political mood expressed in individual remarks and group discussions — one thing stood out with unsettling clarity: the central role of government and the education sector in producing this confusion.

The questions raised, the anxieties voiced, and the contradictions openly displayed were not signs of public apathy. They were symptoms of institutional neglect. People were not confused because they are incapable of understanding federalism; they were confused because no one systematically taught it to them.

When citizens debate the very existence of Puntland versus Somalia inside a federal system, the problem is not the audience — it is the curriculum, the messaging, and the silence of those entrusted with public instruction.

Civic awareness does not emerge spontaneously. It must be cultivated — in schools, universities, civil-service training, public media, and official discourse. Puntland’s government and education authorities abdicated this responsibility for years, and yesterday’s brainstorming merely held up a mirror.

Confusion Produces Flight, Not Loyalty

This mental split has real consequences. When people feel forced to choose between Puntland and Somalia — instead of understanding how the two coexist — they disengage. Some retreat into cynicism. Others relocate physically, politically, or psychologically. You see it in migration patterns, in political apathy, and in how easily external actors exploit internal uncertainty.

A society unsure of its political identity is easy to manipulate.

And manipulation thrives where education is absent.

Leadership Failure, Not Public Ignorance

Let us be clear: this is not the fault of ordinary citizens. It is a leadership failure — collective, prolonged, and unforgivable.

Puntland’s administrations governed budgets, ports, and security forces, but neglected the most critical infrastructure of all: the civic mind. They assumed people would “just understand” federalism by osmosis. They were wrong.

You cannot build a stable polity on assumptions. You must teach it, explain it, debate it, and reinforce it — relentlessly.

Until the Confusion Is Addressed, Instability Will Persist

As long as Puntlanders are trapped in a false binary — Puntland versus Somalia — the region will continue to bleed cohesion. Unity will remain rhetorical. Federalism will remain misunderstood. And politics will remain emotional rather than institutional.

The cure is not louder slogans.

It is serious civic education, honest leadership, and institutional courage.

Puntland and Somalia are not mutually exclusive ideas.

They are incomplete without each other.

Until Puntland’s leaders finally grasp — and teach — that simple fact, this confusion will remain not just a debate, but a danger.

From Consultation to Congress: Puntland Must Rise to the Moment

EDITORIAL

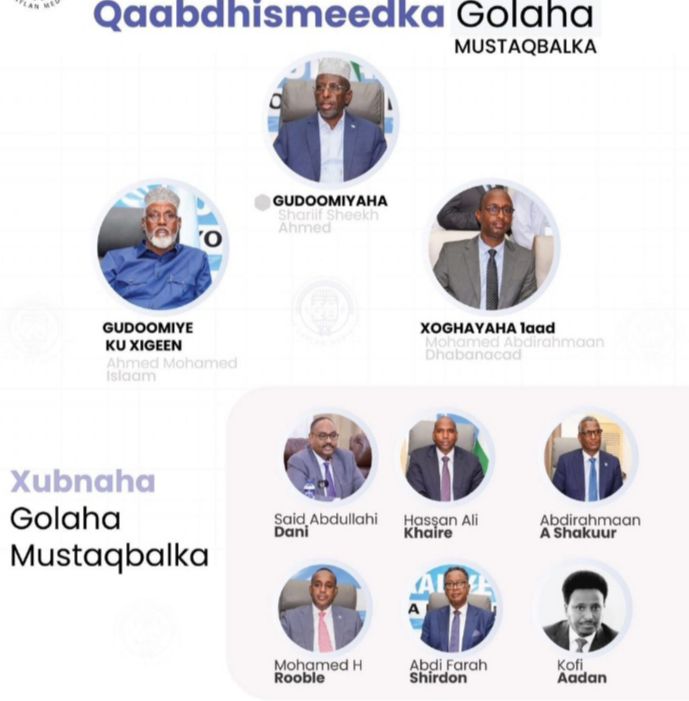

Today’s all-day consultation convened by the President of Puntland State of Somalia, Said Abdullahi Deni, was not an ordinary meeting. It was a rare convergence of accumulated state memory: former cabinet ministers, ex-parliamentarians, veteran security commanders, and leading intellectuals—nearly one hundred minds shaped by war, peace, institution-building, and the hard lessons of Somali federalism. Such a gathering carries a responsibility larger than a communique. It demands elevation.

What unfolded in the Puntland State Presidency at outskirts of Garowe today was not merely “brainstorming.” It was a de facto congress—without the name, mandate, or legitimacy to match its gravity. And that mismatch matters.

Puntland at an Inflection Point

Somalia and the Horn of Africa are entering a dangerous phase: contested sovereignties, collapsing regional norms, external interventions masquerading as partnerships, and an increasingly erratic federal center. Puntland sits at the intersection of these storms—security pressures from extremist networks, constitutional overreach from Mogadishu, and geopolitical tremors from the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden.

At such moments, process becomes substance. History teaches that decisions taken without broad legitimacy—even if correct—are easily delegitimized, resisted, or reversed. Puntland’s own founding in 1998 was not an executive decree; it was a grass-roots congress, painstakingly assembled to produce collective ownership and political durability (cf. Puntland State Formation Conference, Garowe, 1998).

Consultation Is Not Enough

A consultation advises power. A congress authorizes it.

The distinction is not semantic. Under Somalia’s federal dispensation, strategic actions—especially those touching security posture, inter-state relations, and constitutional interpretation—derive legitimacy from collective deliberation, not presidential briefings. This principle is embedded in the logic of the Provisional Federal Constitution, which recognizes shared sovereignty between federal institutions and member states, and—critically—between governments and their constituencies (Somalia Provisional Constitution, Arts. 1, 50).

By stopping at consultation, Puntland risks undercutting the very strategic clarity it seeks. Worse, it signals caution where confidence is required.

Why a Puntland Congress Matters—Now

Transforming this elite gathering into a Puntland Congress would do three essential things:

Anchor Strategy in Legitimacy

Decisions emerging from a congress carry moral and political weight that no executive statement can replicate. They bind institutions, unify elites, and reassure the public that Puntland is acting collectively—not reactively.

Reclaim Institutional Memory

Puntland’s veterans are not ceremonial figures. They are custodians of precedents forged through civil war, state collapse, and regional brinkmanship. A congress converts memory into policy.

Signal Readiness to Friends and Foes

In a region where perception often precedes power, a congress announces seriousness. It tells Mogadishu, neighbors, and international partners that Puntland’s next steps are not improvisations but the outcome of sovereign deliberation.

The Cost of Delay

Somalia’s tragedy is littered with missed moments—times when leaders chose expediency over institution-building. The result has been fragmentation, foreign manipulation, and perpetual crisis management. Puntland has long claimed to be different: rule-based, consultative, and grounded in consent.

This is the moment to prove it.

Elevating this consultation into a Puntland Congress is not a rebuke of the presidency; it is its completion. It would provide the President with a fortified mandate—one capable of sustaining difficult decisions in an unforgiving regional climate.

A Call to Courage

Great leadership is not defined by convening meetings, but by knowing when to formalize history. The brain power is already assembled. The issues are already grave. The hour is already late.

What remains is the courage to name this gathering what it truly is—and allow Puntland, once again, to lead Somalia not by noise, but by constitutional seriousness.

References (selected):

Somalia Provisional Federal Constitution (2012), Arts. 1, 50.

Puntland State Formation Conference (Garowe), 1998—foundational resolutions and communiqués.

——–

Support WAPMEN — the home of fearless, independent journalism that speaks truth to power across Somalia and the region.

Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081.

Somalia’s Perpetual Crisis: How Exclusion and Short-Term Power Doomed the State

Somalia’s tragedy is not merely one of collapse, but of an unending cycle of failed rebirths. The state did not fail solely because it lacked governments or resources. It has consistently failed to rebuild because its would-be architects—across the political spectrum and the clan map—have repeatedly chosen factional control over inclusive nation-building. The conduct of Mogadishu-centered elites since the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) is a stark chapter in this longer story, but it is a symptom of a deeper, systemic disease.

Let us speak plainly, without nostalgia, tribal defensiveness, or historical amnesia.

A Distorted Genesis: The TFG and the Missed Moment

When the TFG was formed in 2004—painfully negotiated and internationally backed—it sought to return to Mogadishu. However, the narrative that city elites simply refused it entry oversimplifies a volatile reality. Mogadishu was not under a unified authority but fragmented among warlords. By 2006, power had consolidated under the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), which brought a harsh but unprecedented stability. The TFG’s entry was not blocked by a petty refusal; it was rendered moot by the rise of a rival, popular governance project. The international and regional decision to empower the TFG to dismantle the ICU via a catastrophic Ethiopian invasion in 2006 was the true pivot. This foreign intervention, invited by a faction within the TFG but opposed by most Somalis, did not fill a passive vacuum. It actively destroyed a Somali political order and birthed the very extremist forces, like Al-Shabab, that would become the enduring crisis. The message became unmistakable: sovereignty was negotiable, and power could be outsourced.

That moment should have triggered national self-reflection. Instead, it inaugurated a politics of denial and dependency, where Somali elites learned to weaponize foreign patronage against domestic rivals.

Sabotaging Federalism: A System Designed to Fail

Federalism was not imposed; it was a Somali compromise to end the centralized tyranny that had fueled civil war. Yet, once codified, it was gutted in practice by a center that demanded obedience and by regional leaders who built personal fiefdoms. The system has collapsed into open confrontation. Puntland has suspended recognition of the federal government over constitutional disputes, while relations with Jubaland have broken down into federal intervention and armed clashes. This is not state-building. It is state capture by multiple, competing centers.

The failure is not Mogadishu’s alone. It is a collective failure of a political class that treats federal units not as pillars of a shared republic, but as clan-based franchises for resource capture and patronage. The “4.5” clan power-sharing model, intended as a temporary fix, has solidified into an engine of zero-sum competition, where governing is about dividing the spoils of port revenues and international aid rather than building common institutions.

The Somaliland Catastrophe and the Illusion of Silence

The most damning evidence of this systemic failure is the handling of Somaliland. For over three decades, successive governments in Mogadishu have oscillated between denial and empty rhetoric, mistaking inertia for strategy. This was not a problem that would fade. While Somalia fractured and talked to itself, Somaliland built de facto institutions. Mogadishu’s chronic irresponsibility created the space for others to act. The reckless Memorandum of Understanding with Ethiopia and the subsequent recognition by Israel in December 2025 were not merely diplomatic coups for Hargeisa; they were the direct harvest of Mogadishu’s strategic neglect. Yet, this too is a Somali tragedy, not a pure victory: Somaliland itself is fractured, its government struggling to control eastern regions that reject its independence project. A problem ignored mutates, but it does not resolve cleanly for anyone.

The Capital That Cannot Be a Capital

At the heart of Somalia’s predicament lies the deadly illusion that controlling Mogadishu equals controlling Somalia. The capital city is treated as a clan estate, the ultimate prize in a war of attrition. By refusing to share it—politically, symbolically, and administratively—dominant actors have turned it from a necessary unifying center into the primary centrifugal force of national fragmentation. This mentality is mirrored in regional state capitals, where local elites replicate the same politics of exclusion. The disease is national.

Failure to Diagnose: Confusing Symptoms for Causes

Worst of all, Somalia’s political class has never honestly diagnosed the illness. They blame foreign conspiracies while perfecting domestic sabotage. They seek foreign troops to hold off enemies created by previous foreign interventions. They confuse militia control with governance, and international recognition with legitimacy.

Somalia’s tragedy is not a lack of intellect or goodwill. Its tragedy is that the logic of its politics—shaped by the trauma of dictatorship, clan fracture, and foreign manipulation—rewards short-term predation over long-term construction. Those who claim to speak for the nation have consistently refused to listen—to history, to other Somalis, and to the clear lesson that no faction can build a state that belongs only to itself.

Until Somalia confronts this original sin—this systemic culture of exclusion, fragmentation, and denied sovereignty—no amount of conferences, constitutions, or foreign troops will save it. A state cannot be rebuilt by those who never accepted that it must belong to all. And Mogadishu will never be the capital of a nation until every Somali, from Hargeisa to Kismayo, believes it has stopped behaving like the capital of a faction. The curse is not the city, but the unbroken, ruinous politics practiced within it.

13 Years of WDM (now WAPMEN) — Fearless, Independent, Uncompromising

Thirteen years ago, Warsame Digital Media (WDM) was born out of a simple but dangerous idea: tell the truth, even when power is uncomfortable with it.

What began as a modest digital platform has grown into a trusted voice for independent Somali journalism, policy analysis, and unapologetic commentary—often standing alone when silence was safer, and conformity more rewarding.

For 13 years, WDM has:

Challenged authoritarian drift, corruption, and political deception

Defended federalism, constitutionalism, and collective sovereignty

Preserved institutional memory against deliberate amnesia

Given voice to citizens, scholars, and dissenters excluded from official narratives

Refused funding, patronage, or protection that demanded compromise

WDM has survived threats, censorship, character assassination, isolation, and financial hardship—not because the road was easy, but because the mission was necessary.

In an era of shrinking civic space, manufactured consent, and media capture, WDM chose the harder path: independence without apology.

This anniversary is not a celebration of longevity alone.

It is a reckoning—with those who abused power, distorted history, and mistook silence for consent.

To our readers, contributors, critics, and supporters across Somalia and the diaspora:

You kept this platform alive.

To those who hoped WDM would fade:

We are still here.

And to the next generation of truth-tellers:

The fight continues.

13 Years Strong.

13 Years Unbought.

13 Years Unbroken.

— Warsame Digital Media (WDM)

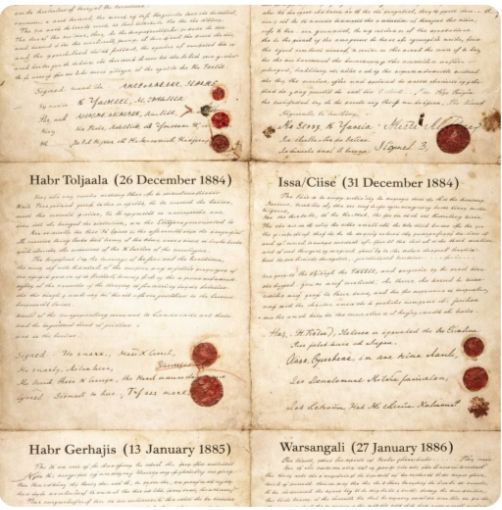

White Paper: Colonial Treaties, Clan Territories, and the Limits of Unilateral Sovereignty Claims in Northern Somalia

Executive Summary

This policy paper examines the legal status of colonial-era treaties between the British administration and northern Somali clans and assesses their relevance to post-1991 sovereignty claims. It argues that these treaties collectively established the British Somaliland Protectorate as a colonial administrative unit, not clan-owned sovereign entities. All such treaties were extinguished by the 1960 Union of British and Italian Somaliland, transferring sovereignty to a unified Somali Republic. The collapse of the Somali state in 1991 did not revive colonial treaties nor dissolve Somalia’s international legal personality. Consequently, Somaliland cannot obtain international recognition without Somalia’s consent through negotiation, as required by international law governing state continuity, territorial integrity, and secession.

1. Introduction

Since 1991, claims to sovereignty in northern Somalia have frequently invoked colonial-era treaties as a legal foundation for unilateral independence. This paper evaluates such claims against established principles of international law, including state succession, territorial integrity, and recognition. It demonstrates that colonial treaties do not confer enduring sovereign rights on clans and cannot be selectively resurrected to justify unilateral recognition.

2. Colonial Treaties and the Formation of the British Somaliland Protectorate

Treaties concluded between Britain and northern Somali clans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were instruments of colonial administration. Under international law, treaties concluded between colonial powers and non-state entities did not create sovereign equals nor vest sovereignty in local signatories (Shaw, 2017; Crawford, 2006).

Collectively, these agreements constituted the British Somaliland Protectorate, whose external borders were fixed by inter-imperial agreements between Britain and Italy. They did not:

Create independent clan states

Transfer sovereignty to clans

Establish inheritable territorial title

Colonial sovereignty resided exclusively in the administering power.

3. Dhulbahante Territory and Colonial Incorporation by Occupation

Dhulbahante territories were incorporated into the Protectorate through colonial occupation, following the defeat of Sayid Mohamed Abdulle Hassan and the collapse of the Dervish Movement. International law recognizes occupation as a lawful mode of colonial territorial acquisition during that period (Shaw, 2017).

This history confirms that the Protectorate was not a voluntary confederation of clans but a colonial construct established through mixed methods of treaty and force.

4. Colonial Borders vs. Clan Borders

International law distinguishes between administrative colonial borders and internal social or customary boundaries. Colonial borders defined the territorial scope of the colony for purposes of administration and later state succession; they did not abolish internal communal land tenure or clan territoriality (Crawford, 2006).

The principle later known as uti possidetis juris preserved colonial administrative borders at independence to prevent conflict—not to reallocate internal ownership or sovereignty (ICJ, Burkina Faso v. Mali, 1986).

5. Legal Extinguishment of Colonial Treaties by the 1960 Union

Upon independence and union in 1960, sovereignty passed from the colonial administrations to the Somali Republic as a single successor state. Under the law of state succession:

Colonial treaties lapse unless expressly preserved

Sovereignty vests in the successor state, not sub-state entities

Internal groups do not retain a right of unilateral withdrawal

This position is consistent with the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978) and customary international law (Crawford, 2006).

6. Post-1991 Collapse and the Continuity of the Somali State

The collapse of Somalia’s central government in 1991 did not terminate Somalia’s international legal personality. Under international law, statehood is not extinguished by governmental collapse (continuity doctrine). Somalia retained UN membership, treaty capacity, and territorial integrity (Shaw, 2017).

The International Court of Justice has repeatedly affirmed that internal instability does not dissolve statehood (Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall, Advisory Opinion, 2004).

7. Recognition, Secession, and the Requirement of Negotiated Consent

International law strongly disfavors unilateral secession from an existing sovereign state. Outside the context of decolonization, recognition of a breakaway entity requires the consent of the parent state, except in exceptional cases of remedial secession.

In its Kosovo Advisory Opinion (2010), the ICJ deliberately avoided recognizing a general right to unilateral secession and emphasized the primacy of territorial integrity in relations between states.

Somaliland’s case does not qualify as:

Decolonization (self-determination was exercised in 1960), nor

Remedial secession (no sustained denial of internal self-determination meeting the high threshold recognized in doctrine)

Accordingly:

Somaliland cannot lawfully obtain international recognition without Somalia’s consent

Such consent can only arise through formal negotiation with the internationally recognized Somali state

Recognition absent consent would violate Somalia’s territorial integrity under UN Charter Article 2(4) and UN General Assembly Resolution 2625 (1970)

International practice—from Sudan/South Sudan to Ethiopia/Eritrea—confirms that negotiated separation, not unilateral declaration, is the lawful pathway.

8. Policy Implications

For Somali stakeholders:

Sustainable political outcomes must be negotiated, inclusive, and legally grounded. Colonial reinterpretation offers no lawful shortcut.

For international actors:

Recognition without Somalia’s consent would contravene settled international norms and set a destabilizing precedent.

For mediation frameworks:

Dialogue should focus on negotiated constitutional or confederal arrangements rather than unilateral recognition strategies.

9. Conclusion

Colonial treaties in northern Somalia established a colonial administration, not sovereign clan entities. These treaties were extinguished by the 1960 Union, transferring sovereignty to a unified Somali state. The 1991 collapse did not revive colonial arrangements nor authorize unilateral secession.

Somaliland cannot secure international recognition without Somalia explicitly letting it go through negotiation. Any alternative approach lacks legal foundation and contradicts international law on state continuity, territorial integrity, and recognition.

References (International-Law Sources)

Crawford, J. (2006). The Creation of States in International Law (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Shaw, M. N. (2017). International Law (8th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

International Court of Justice (1986). Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso v. Mali), Judgment.

International Court of Justice (2004). Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion.

International Court of Justice (2010). Accordance with International Law of the Unilateral Declaration of Independence in Respect of Kosovo, Advisory Opinion.

United Nations (1945). Charter of the United Nations, Article 2(4).

United Nations General Assembly (1970). Resolution 2625 (XXV): Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations.

Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978).

The Rule of the Jungle Returns: When Power Replaces Law

WAPMEN EDITORIAL

The mask has slipped. The pretense of a civilized international order has evaporated, revealing a hollow stage. When Israel razed Gaza, killing civilians en masse while the world watched—paralyzed, mute, complicit—we learned a brutal lesson: there is no referee left on the field.

That moment was not an aberration. It was a signal flare.

What followed was predictable. If impunity is rewarded, it becomes doctrine. If international law is optional for the powerful, it becomes irrelevant for everyone else. Gaza is not only a graveyard of innocents; it is the funeral of a global system.

The Death of the Umpire

Let us speak plainly: there is no United Nations anymore—not in any meaningful sense. There are buildings, budgets, and bureaucrats. There are speeches, statements, emergency sessions, and vetoes. But there is no enforcement, no moral authority, no deterrence. International law has been reduced to a pamphlet—waved by the weak, shredded by the strong.

Human rights? Selective. War crimes? Contextual. Genocide? Debated. Justice? Deferred—forever.

This is not a failure of capacity; it is a failure of will. The system was not overwhelmed; it was captured.

From Gaza to the World

Once the precedent is set, the contagion spreads. If mass killing can be televised without consequence, why should others restrain themselves? If borders can be violated with applause from allies, why respect sovereignty elsewhere?

Today the names whispered are Venezuela and Iran. Tomorrow, it will be someone else. The lesson has been absorbed: power, not principle, decides. Might does not just make right—it erases the question altogether.

We are not drifting toward chaos; we have institutionalized it.

The New Normal: Permanent War

What is emerging is not a single world war, but something more insidious: a permanent state of global confrontation—proxy wars, sanctions wars, cyber wars, economic strangulation, information warfare—all unfolding simultaneously, everywhere. The battlefield is no longer defined; it is ambient.

And the victims are always the same: civilians, the poor, the stateless, the voiceless. Gaza today. Somewhere else tomorrow.

This is not a future imagined by dystopian fiction; it is a present engineered by geopolitical arrogance.

Somalia and the Periphery Beware

For fragile states—Somalia among them—the implications are dire. When international law collapses, small nations lose their only shield. Sovereignty becomes negotiable. Recognition becomes transactional. Fragmentation becomes profitable for outsiders.

When the jungle rules, the smallest creatures are the first to be trampled.

A World Without Restraint

We were told “never again.” What they meant was “never again—for us.” The rest of humanity can queue for condolences.

This is the dreadful truth we now inhabit: a world without restraint, without accountability, without shame. A world where the powerful act first and explain later—if at all.

What we are waiting for now is not peace, but escalation. Not diplomacy, but alignment. Not justice, but survival.

The jungle is back. And it is hungry.

———-

Support WAPMEN — the home of fearless, independent journalism that speaks truth to power across Somalia and the region.

Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081.

Strategic Silence Is Not Neutrality — It Is a Choice

WAPMEN Editorial

When a sovereign state is openly violated, silence is never innocent. It is calculative.

In the wake of Israeli aggression—recognizing a region of Somalia as an independent state in brazen violation of international law—the world did not speak with one voice. Many did the right thing. Regional blocs, international organizations, and responsible states rose to defend Somalia’s territorial integrity, the sanctity of borders, and the fragile legal order that still pretends to govern international relations.

Others chose to wait.

This strategic silence—particularly from Somalia’s immediate neighborhood—is neither accidental nor benign. It reveals two uncomfortable truths that Mogadishu, Garowe, Hargeisa, and every Somali citizen must confront without illusion.

Silence Option One: Sinister Self-Interest

Some actors see Somalia not as a state to be defended, but as a chessboard to be exploited.

In a region already saturated with proxy wars, port rivalries, military basing, and intelligence games, Somalia’s fragmentation is not a tragedy—it is an opportunity. Silence, in this context, is consent by omission. It keeps doors open for future leverage:

Access to ports and airspace

Strategic footholds along the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden

Influence over fractured Somali authorities desperate for recognition or protection.

For these actors, condemning Israeli recognition would be inconvenient. It would limit their room to maneuver. So they wait, watch, and calculate—hoping Somalia’s weakness will ripen into concession.

Silence Option Two: Extortion by Delay

Others are practicing a more refined diplomacy: transactional patience.

They are withholding public support not because they disagree with Somalia’s position, but because they want something in return—quietly, privately, and urgently.

Votes. Contracts. Security arrangements. Diplomatic alignment. Intelligence cooperation.

This is not principled neutrality. It is leverage politics. Somalia’s sovereignty becomes a bargaining chip; its crisis, a negotiating table.

Time, they believe, will soften Somalia’s resolve.

International Law Is Not a Buffet

Let us be clear: the recognition of a breakaway region without the consent of the parent state violates the UN Charter, the principles of the United Nations, and the founding norms of the African Union. If these rules apply only when convenient, then no African state is safe—least of all those with internal tensions and unfinished nation-building projects.

Those who remain silent today are not hedging; they are eroding the very rules that protect them tomorrow.

Somalia Must Read the Room—Coldly

Somalia should welcome the solidarity it has received. But it must also document the silence.

History remembers who spoke when it mattered—and who calculated instead. Strategic ambiguity has consequences. When the precedent is set that borders can be redrawn by external actors, silence becomes complicity.

Somalia does not need heroes. It needs clarity.

And clarity begins with naming silence for what it is:

either self-interest masquerading as diplomacy,

or concessions dressed as patience.

Time will tell—but only if Somalia stops waiting for it to speak.

WAPMEN

Fearless analysis. Uncomfortable truths. No strategic silence.

Who Is Watching the Fire While the House Burns? Inflation, Dollarization, and the Crisis of Priority in Somalia

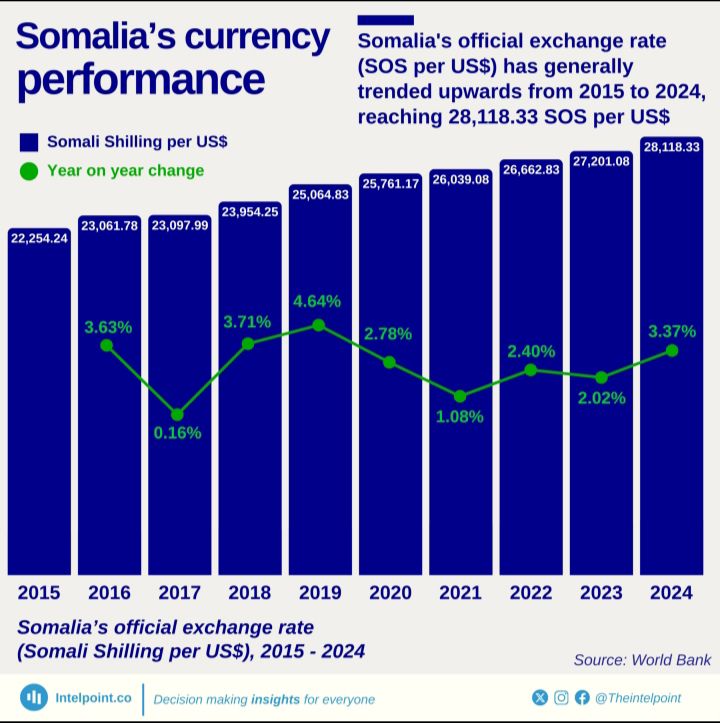

There is a silent emergency stalking Somalia—not always announced by sirens, rarely the central debate in parliament, and too often a footnote in presidential speeches. It is the slow, grinding violence of an economic system that imports its prices and exports its sovereignty. The most damning question is not whether anyone is watching, but whether the watching is matched by action that reaches the poor.

A Country with a Currency It Cannot Control

Somalia’s economy runs on the US dollar, a foreign currency whose value is decided in Washington and global markets. When shocks hit—wars, banking crises, or interest rate hikes abroad—Somali households pay the price immediately. Bread costs more. Fuel spikes overnight.

This is the brutal arithmetic of a country that imports over 60% of its GDP. The poor are left naked before global storms. The woman selling vegetables earns in shillings but buys wholesale in dollars. The displaced family negotiates rent in a currency tied to recessions an ocean away.

The Illusion of Neutrality in a Digital Dollar Economy

Dollarization is not neutral; it is a regressive tax on the poor, but its mechanism is more modern than cash. The economy survives on fragile inflows of dollars from remittances (about 27% of GDP) and aid, which flow out just as fast to pay for imports, creating a chronic trade deficit exceeding $5 billion.

Most transactions use digital dollars via telecom networks. However, these companies can use the hard currency they collect for their own external business, creating an artificial scarcity of physical cash within Somalia. This paradox—a digital dollar economy starving for paper cash—drives up costs for everyone, especially those outside the digital fold.

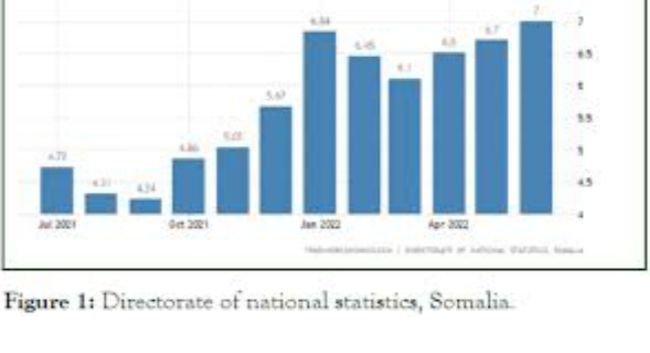

The Chasm Between Institutional Reform and Daily Survival

Contrary to the claim that no one is watching, institutions are trying to build the watchtower in the middle of the storm. The Somali National Bureau of Statistics reports inflation, which was 3.9% as of October 2025. The Central Bank of Somalia (CBS) is actively reforming, with a dedicated policy group and a sequenced plan: first, build financial infrastructure and regulate mobile money; later, perhaps reintroduce a national currency.

Yet, these vital but technical reforms exist in a parallel universe to the daily crisis faced by the 54% of the population (over 10 million people) living below the poverty line. With nearly 400,000 youth entering the job market each year in a stagnant economy, per-capita income does not grow. This is the core disconnect: while experts design payment systems and regulations, mothers count coins that buy less every week.

Leaders Argue Over Power While the Foundation Cracks

The political sphere remains consumed by survival—the survival of leaders. Disputes over elections, federal power-sharing, and clan arithmetic create paralysis, preventing a unified response to the economic emergency.

While they quarrel, foreign powers and businesses deal with Somalia not as a sovereign state but as an unmanaged space, extracting ports, security contracts, and political loyalty. The state fragments, and the demographic pressure cooker ticks: 70% of the population is under 30, waiting for a future that is not being built at the speed it is needed.

What Must Be Said: The Fire and the Firehouse

A country that debates inflation statistics while ignoring the cost-of-living anguish is in crisis. A leadership that obsesses over staying in office while citizens sink into poverty is losing its way.

Somalia’s tragedy is not a lack of plans. It is the agonizing gap between long-term institutional rebuilding and immediate human desperation. The Central Bank is trying to rebuild the firehouse—creating a Financial Stability Committee, drafting new banking laws, launching national payment systems. But for the family watching their purchasing power burn, the reforms feel like a blueprint delivered as the embers fly.

The question is not “Who is watching the fire?” The CBS is watching. The Bureau of Statistics is measuring the smoke. The real, unanswered question is: Who will bridge the chasm between the reform documents in Mogadishu and the empty market stalls in Baidoa, Garowe, and Kismayo?

Until inflation, currency sovereignty, and social protection are treated with the same urgency as political survival, Somalia will remain what it is today: a nation where the house burns, not for lack of firefighters, but because they are building the fire engine next to the flames.

—

Support Independent Journalism

To continue fearless, fact-based reporting that speaks truth to power across Somalia and holds both suffering and reform to the light, support independent journalism.

Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081.

WAPMEN EDITORIAL | Declassified Fiction: When CIA Paperwork Rewrites Somali History

https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP87T00289R000100460001-8.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

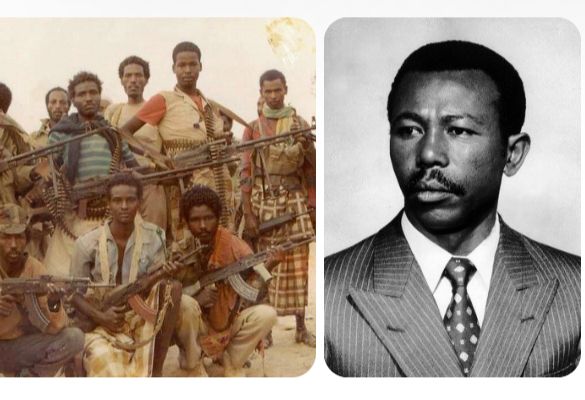

A newly circulated declassified CIA document is being waved around as if it were a final arbiter of Somali history. It is not. On the critical question of the Somali resistance movements of the 1980s—and specifically the arrest of Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed—the document is factually wrong, historically careless, and politically misleading.

Let us be precise and put the record straight.

False Claim #1: Abdullahi Yusuf Opposed an SSDF–SNM Merger

False. Flatly false.

The document alleges that Abdullahi Yusuf opposed a merger between the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF) and the Somali National Movement (SNM). This reverses reality.

Historical fact:

SSDF was the older, structured, and umbrella resistance movement—already composed of three organized factions—operating from Ethiopian territory years before SNM emerged as a major force. It was SNM that declined to join SSDF, not the other way around. The refusal was rooted in strategic autonomy and internal political calculations within SNM, not hostility or obstruction from SSDF leadership.

To suggest Abdullahi Yusuf blocked unity is to invert the burden of decision-making and misread the political dynamics of the era.

False Claim #2: Ethiopia Arrested Abdullahi Yusuf for Anti-Unity Politics

Again, false.

The CIA paper asserts that Ethiopian authorities detained Abdullahi Yusuf because he resisted inter-movement unity. That is a convenient fiction.

Historical fact:

Abdullahi Yusuf was arrested by order of Mengistu Haile-Mariam—not for opposing Somali unity, but for political disagreements over the control, direction, and independence of SSDF vis-à-vis Ethiopian security dictates. Addis Ababa expected compliance; Abdullahi Yusuf insisted on Somali decision-making autonomy.

That defiance had consequences.

This was a power struggle, not an ideological schism over unity.

What Really Happened

SSDF predated SNM and functioned as a multi-faction resistance platform.

SNM chose not to merge with SSDF; this was a strategic choice, not a rejection by SSDF.

Ethiopia arrested Abdullahi Yusuf because he resisted Ethiopian micromanagement of Somali resistance politics—not because he opposed unity.

The detention reflected Cold War patron–proxy tensions, not Somali inter-movement hostility.

These facts are well-known to participants, contemporaries, and serious historians of the Somali liberation era.

The Declassified Trap

Declassified does not mean accurate. Intelligence documents often capture:

Partial briefings

Informant bias.

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/17geZVDMge/

Strategic misinterpretation

Or outright political convenience

When such documents are lifted from their context and treated as gospel, history is not revealed—it is distorted.

Somalia’s past cannot be footnoted into existence by Langley memos written at a distance, filtered through regional agendas, and blind to internal Somali political realities.

WAPMEN Verdict

This CIA document fails the historical test. It misattributes motives, reverses agency, and erases the real cause of Abdullahi Yusuf’s arrest: his refusal to subordinate Somali resistance to foreign command.

Somalia deserves better than recycled intelligence myths masquerading as history.

————

WAPMEN — Warsame Policy & Media Network

Critical analysis, fearless rebuttals, and historical accountability.

Villa Somalia’s Crisis of Authority: How Federal Failure Invites National Disintegration

The Israeli government’s recognition of Somaliland is not merely a diplomatic shock; it is a glaring symptom of chronic dysfunction at the heart of Somalia’s federal government in Villa Somalia. States do not fragment solely because of external conspiracies. They disintegrate when the governing center loses its legitimacy, competence, and authority, yet continues to issue commands as if its power were unchallenged.

For years, Mogadishu has issued proclamations it lacks the capacity to enforce. This “paper sovereignty” is dangerously exposed when a federal center, failing to secure even the wider vicinity of the capital, attempts to rule like a unitary command post. This contradiction invites defiance, accelerates the isolation of regions, and creates a vacuum that foreign powers are all too eager to fill. That door has now been kicked open.

Decrees Without Capacity Breed Fragmentation

A government that does not fully control its capital cannot credibly dictate the political destiny of distant regions. Yet Villa Somalia persists in a paradox: employing rhetoric of maximum centralization while possessing minimum state capacity. The result is a predictable spiral: regions hedge their bets, local elites seek external guarantors, and diplomacy becomes a transactional free-for-all.

Thus, the Israeli move is not because Somaliland discovered a magic key to recognition, but because Somalia’s federal center has neglected the hard, consensus-based work of unity. Instead of fostering negotiation, constitutional restraint, and genuine power-sharing, it has pursued unilateralism. Key Federal Member States like Puntland and Jubaland have suspended cooperation with Mogadishu over disputes about the 2026 electoral process, with some opposition groups forming a parallel “Council for the Future of Somalia”.

Security Failure and Political Overreach

The government’s fragility is most stark in the security sector. Despite an initial offensive, al-Shabaab has resurged, recapturing territory in Middle Shabelle and demonstrating the ability to launch high-profile attacks in Mogadishu, including a recent attempt on the president’s convoy. Meanwhile, the fight against the Islamic State in Somalia (ISS) in Puntland is being waged primarily by regional forces with little support from the federal government.

This security crisis unfolds alongside a political power grab. The government’s unilateral push for a “one person, one vote” model for the 2026 elections—an ideal most agree is currently unfeasible—is widely seen as a maneuver to concentrate power and extend its mandate. By unilaterally changing electoral laws and packing commissions with loyalists, Villa Somalia is dismantling the fragile federal settlement, not defending it.

The Open Market of Influence

Somalia’s internal incoherence has turned the country into an open market for foreign influence, where global actors bargain directly with sub-state authorities. The list is long: Israel, Turkey, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Gulf states all play their parts. This does not happen in a vacuum. It happens when the center cannot bind the periphery to a shared national project.

The international reaction to Israel’s move is telling. While it was celebrated in parts of Somaliland, it triggered widespread protests across Somalia and near-universal diplomatic condemnation. The African Union, Arab League, Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and regional bloc IGAD all reaffirmed support for Somalia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. This global stance highlights that the problem is not a lack of external support for Somali unity, but internal actions that erode it.

Has Villa Somalia Learned Anything?

That is the most damning question. The silence is an answer. There has been no fundamental reckoning, no admission that sovereignty cannot be enforced by press releases. Instead, we hear more orders and denunciations while the structural rot deepens. The government is now poised to assume the rotating presidency of the UN Security Council in January 2026—a symbolic victory that will only magnify its domestic contradictions on a global stage.

If Villa Somalia continues to confuse command with consent, Somalia will not merely face recognition gambits; it will face managed disintegration. The path back requires an urgent return to consensus: halting unilateral constitutional changes, agreeing on a feasible and inclusive electoral model for 2026, and rebuilding cooperative security frameworks with the Federal Member States.

WAPMEN’s bottom line:

You cannot shout unity from a palace you cannot project authority from. You cannot defend sovereignty while hollowing out federal trust. And you cannot stop foreign exploitation without first fixing the broken politics at the center. Until Villa Somalia learns this, every new “diplomatic shock” will be less a surprise and more an indictment.

Somaliland’s Gamble: A Dangerous Bargain with a Pariah State

The recognition of Somaliland by Israel is not a diplomatic breakthrough; it is a perilous trap. In a desperate bid to end three decades of international isolation, the leadership in Hargeisa has shaken hands with a partner that is itself increasingly isolated, morally compromised, and engaged in multiple regional wars. Far from unlocking a path to global acceptance, this move has triggered a unified wall of international condemnation, entangled Somaliland in the geopolitics of the Middle East, and exposed it to severe and unforeseen security and political risks.

A Chorus of Condemnation, Not a Bandwagon of Recognition

Contrary to Somaliland’s hopes, Israel’s move has not sparked a wave of followers. Instead, it has provoked a near-universal diplomatic backlash that has reinforced Somaliland’s isolation.

Somalia’s government, calling the recognition a “naked invasion” and an “existential threat,” has declared it null and void, vowing to pursue all diplomatic and legal avenues in response.

The response from regional and international bodies has been unequivocal:

· The African Union (AU) firmly rejected the move, warning it “sets a dangerous precedent” for peace and stability across the continent and undermines the sacrosanct principle of colonial-era borders.

· A bloc of 21 Arab and African nations and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation issued a joint statement condemning the recognition as a grave violation of international law.

· Key regional powers, including Egypt, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Djibouti, have all stood with Somalia, rejecting the agreement.