By WARSAME DIGITAL MEDIA (WDM)

A President Who Needs a Foreign Microphone

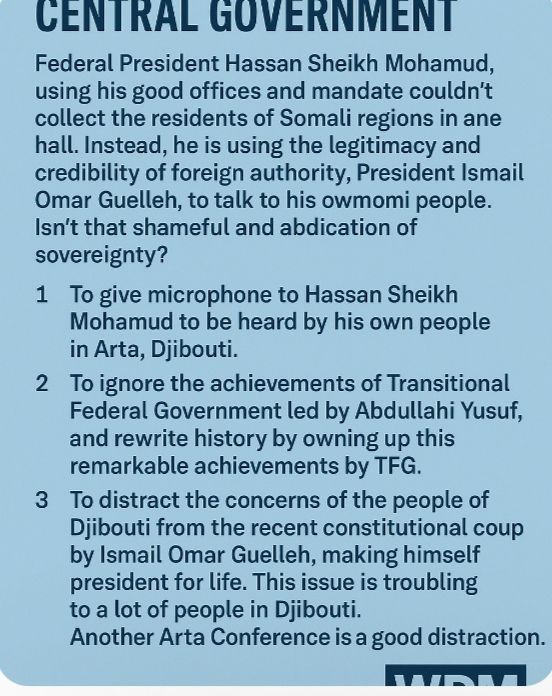

It is one of the strangest spectacles in modern African politics: a head of state who cannot gather his own citizens on his own soil — not in Mogadishu, not in Baidoa, not in Garowe, not even in Laascaanood — but must instead borrow the stage of a foreign autocrat to speak to his own people. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, the self-proclaimed defender of Somali unity, has found himself standing not as a host but as a guest, addressing Somalis from Arta, Djibouti — a rented hall under another man’s flag.

The symbolism is deafening. The so-called Federal President uses another country’s legitimacy to perform his national duty. What does it say about sovereignty when the President of Somalia needs to be introduced to his own citizens by President Ismail Omar Guelleh? It’s like a father asking the neighbour’s permission to talk to his own children — a tragic comedy of failed statehood.

Arta 2025: The Sequel Nobody Asked For

The “25th Anniversary of the Arta Conference” is being paraded as a historic reunion — but in truth, it is a desperate rerun of a tired political play. What’s the real purpose of this show? Three things stand out clearly.

1. Microphone Diplomacy: Guelleh provides the microphone, Hassan Sheikh provides the speech. The Somali President, stripped of domestic credibility, borrows the voice of Djibouti’s palace to make himself heard. A President speaking to Somalis in exile — what a metaphor for the state of Somalia itself.

2. Historical Theft: The gathering attempts to erase the legacy of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) founded by Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, the only Somali leader who built a legitimate post-war central authority and marched it back to Mogadishu and sat in Villa Somalia after Siyad Barre. Arta 2025 is not about peace; it’s about plagiarism. Hassan Sheikh and his Damul Jadiid courtiers are trying to rewrite history, pretending the TFG never existed — as if the journey from Nairobi to Mogadishu happened by divine teleportation, not by political courage.

3. Djibouti’s Domestic Distraction: Let’s not fool ourselves — Guelleh’s new “Arta show” is a smokescreen. His recent constitutional coup, extending his rule into eternity, has angered many Djiboutians. What better way to divert attention from domestic unrest than to resurrect Somalia’s endless conferences? While Djibouti’s youth whisper about political reform, Guelleh waves the Somali flag and declares another “peace initiative.” The irony? There is no peace to be made — just recycled rhetoric and hotel per diems.

But make no mistake: The elephants in the Arta Hall now are TFG and Puntland State.

The Puppet and the Puppeteer

In this theatre of borrowed legitimacy, two aging regimes perform a duet of self-preservation. Hassan Sheikh Mohamud needs Guelleh’s stage to look relevant. Guelleh needs Hassan Sheikh’s chaos to look indispensable. One is struggling to control his federation; the other is struggling to control his own succession. Together they form a tragic alliance of political insecurity.

The Somali President, who once promised “Soomaali Heshiis Ah,” now acts like a tenant of Djibouti’s foreign policy. His ministers chase after photo opportunities instead of federal consensus. Meanwhile, Guelleh, the octogenarian master of political disguise, plays the “wise regional statesman” while chaining his own citizens to perpetual rule.

The Real Message of Arta

The 2025 Arta Conference does not symbolize reconciliation — it symbolizes regression. It marks the return of Somalia’s dependency politics, where every local crisis requires a foreign sponsor, and every Somali leader kneels before a smaller but more coherent state.

If Hassan Sheikh Mohamud cannot summon his own citizens in Mogadishu without foreign permission, then what exactly is he president of? And if Ismail Omar Guelleh’s only legacy after 25 years in power is hosting other people’s problems, then what is Djibouti’s independence worth beyond its borders?

Final Word: The Emperor and the Errand Boy

Somalia’s President borrows legitimacy; Djibouti’s President hides from his own people. One cannot speak at home, the other cannot stop speaking abroad. Together they create the perfect paradox — two leaders bound by insecurity, united by illusion, and blessed by self-deception.

In the end, Arta 2025 will not be remembered for speeches or resolutions. It will be remembered as a political masquerade — where a nation without direction applauded another without democracy.

——

WARSAME DIGITAL MEDIA (WDM)

Support WDM — the home of fearless, independent journalism that speaks truth to power across Somalia and the region.

Tel/WhatsApp: +252 90 703 4081.

You must be logged in to post a comment.