Abstract

This article challenges selective historical narratives that portray Somaliland as uniquely victimized under Siad Barre and thus uniquely justified in pursuing unilateral secession from Somalia. By reconstructing a national timeline of repression and armed resistance, the study highlights the foundational role of the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), the first and most inclusive armed opposition to Barre’s regime. Drawing on scholarly and human rights sources, the analysis demonstrates that SSDF significantly weakened Barre before the United Somali Congress (USC) ousted him in 1991, and that Somali state violence targeted communities nationwide, not exclusively in Somaliland. The article also highlights an often-overlooked fact: SSDF financed and armed the Somali National Movement (SNM) during its formative years, even negotiating unification between the two fronts. The article argues that Somali fragmentation has been driven as much by historical distortions as by genuine grievances, and that federalism, exemplified by Puntland, provides a more inclusive framework than secession for addressing Somalia’s collective past.

Keywords: Somalia, Somaliland, SSDF, USC, SNM, Siad Barre, secession, federalism, Somali civil war

Introduction

Since Somaliland’s unilateral declaration of independence in May 1991, its proponents have sought to ground secession in a narrative of exceptional victimhood at the hands of Somalia’s central state. The argument is that the north suffered unique atrocities under Siad Barre’s regime, justifying permanent separation. While the suffering of Somalilanders was real and severe, this narrative omits critical facts: authoritarian repression was nationwide, and the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF)—not the Somali National Movement (SNM) or United Somali Congress (USC)—was the first and most inclusive armed opposition to the regime.

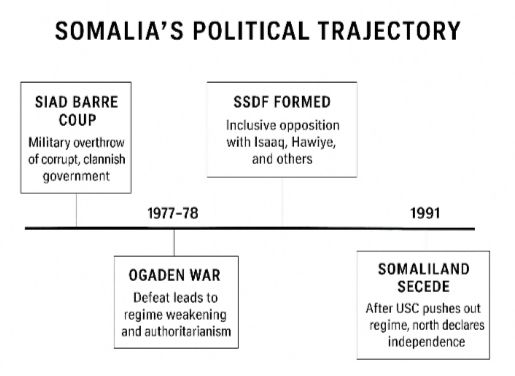

This article re-situates Somaliland’s experience within Somalia’s broader political trajectory. By emphasizing SSDF’s pioneering role—including its support of SNM in its early years—it challenges historical distortions and underscores the federalist alternative embodied by Puntland.

The 1969 Coup and Revolutionary Reforms

In October 1969, Major General Mohamed Siad Barre led a coup following the assassination of President Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke. The ousted civilian government was widely perceived as corrupt and clannish, dominated by a Majeerteen president and an Isaaq prime minister (Adam, 1994). The coup was welcomed nationwide, including in the northern regions.

The early years of the Supreme Revolutionary Council (1969–1974) witnessed progressive reforms: adoption of the Latin script in 1972, mass literacy campaigns, advances in women’s rights, and rhetorical campaigns against clannism (Lewis, 2002). These reforms initially created optimism, before the regime descended into authoritarianism.

The Ogaden War and the Rise of Opposition

Somalia’s defeat in the Ogaden War (1977–78) marked a turning point, weakening the regime and intensifying authoritarian control (Samatar, 1988). In response, opposition movements emerged, the earliest and most significant being the SSDF.

Founded in Ethiopia in 1978 by exiled officers after a failed coup, SSDF was remarkable for its inclusivity. It was chaired by Mustafe Haji Nur (Isaaq), with Omar Sterlin (Hawiye/Abgaal), once a mayor of Mogadishu, as vice-chairman, and later Mohamed Farah Jamaale (Hawiye/Habar Gidir) in leadership (Compagnon, 1992). While Majeerteen formed a strong base, SSDF’s outlook was pan-Somali, setting it apart from later clan-based movements such as SNM (Isaaq) and USC (Hawiye).

SSDF and the Formation of SNM

One of the most overlooked aspects of Somali opposition history is the relationship between SSDF and SNM. When SNM was formed in London and later based in Ethiopia in 1981, it faced acute resource shortages and organizational fragility. For roughly three years following SNM’s founding, SSDF supplied it with weapons, military hardware, and financial resources.

Moreover, SSDF leaders held negotiations with successive SNM chairmen—Ahmed Ismail Abdi “Duqsi,” Colonel Abdikadir “Koosaar,” and Yusuf Sheikh Ali Madar—seeking to unify the two fronts into a single armed opposition. Though these efforts failed, they illustrate that SSDF envisioned the Somali struggle as a collective national project rather than a set of regional or clan-based rebellions (Lefebvre, 1991).

This critical historical fact undermines claims that SNM’s struggle was wholly autonomous or exclusively grounded in northern exceptionalism.

SSDF’s Role in Weakening Barre

By the early 1980s, SSDF had already significantly weakened Siad Barre’s regime. Its insurgency drained resources, eroded military cohesion, and exposed the regime’s fragility (Laitin & Samatar, 1987). Mengistu Haile Mariam’s manipulation and sabotage of SSDF reduced its effectiveness, yet its campaigns in Mudug, Nugaal, and Galgaduud forced the regime into brutal retaliations, including destruction of wells and massacres of civilians (Human Rights Watch, 1990).

Later opposition movements built on these openings. The USC itself emerged as a splinter faction of SSDF, led by Hawiye leaders such as General Mohamed Farah Aidid (Menkhaus, 2003). Meanwhile, SNM, strengthened by earlier SSDF support, pursued its campaigns in the northwest.

Repression as a Nationwide Phenomenon

Contrary to secessionist claims, Siad Barre’s repression was not regionally isolated.

In the northeast, Majeerteen civilians were massacred, and vital wells destroyed during anti-SSDF campaigns (Human Rights Watch, 1990).

In the northwest, Hargeisa and Burco were bombarded in 1988 during SNM’s uprising (Africa Watch, 1990).

In the capital, Hawiye communities suffered massacres in 1989–1990 (Amnesty International, 1990).

Thus, state violence was systematic and nationwide, targeting communities wherever opposition movements emerged.

Collapse and Aftermath

By 1990, Siad Barre’s regime was mortally weakened by years of SSDF insurgency, combined with the intensified offensives of SNM and USC. In January 1991, the USC captured Mogadishu, forcing Barre into exile. In May of that year, SNM declared Somaliland’s unilateral re-independence.

Even after Barre’s fall, SSDF continued to defend Somali unity. When Aidid’s USC attempted to seize Galkayo, SSDF militias repelled them, safeguarding the northeast (Prunier, 1995). This resistance provided the foundation for Puntland’s creation in 1998, a federalist entity committed to Somali unity rather than secession (Hoehne, 2015).

Competing Futures

The post-Barre collapse produced divergent political trajectories:

Somaliland, rooted in SNM’s legacy, pursued secession.

Puntland, drawing on SSDF’s inclusive federalist vision, advanced unity through autonomy.

South/Central Somalia, dominated by USC splinters, descended into destructive warlordism.

Among these, Puntland’s federalist experiment represents the most inclusive response to Somalia’s shared history of repression.

Conclusion: The Unabated Political Trajectory

The historical distortions around Somaliland’s unilateral secession often ignore the deeper trajectory of Somali politics since 1969. From Siyad Barre’s initial reforms, through the rise of SSDF as an inclusive opposition movement, to its role in materially supporting SNM and weakening the regime before USC’s final push, the record shows a complex interplay of national unity efforts, factional rivalries, and external manipulation.

Yet this trajectory did not end with the collapse of Siyad Barre. The current federal system, established after the 2004 Transitional Federal Government, was meant to resolve Somalia’s governance crisis and balance federal autonomy with national unity. However, the reality has been far less promising. Today, Somalia’s political trajectory continues unabated under an ineffective federal system that is being sabotaged from within by its federal leaders. Instead of building inclusive institutions, these leaders have often entrenched clannism, weakened cooperation with federal member states, and undermined the very unity the federal system was designed to safeguard.

This ongoing dysfunction underscores the continuity of Somalia’s political crisis: a state oscillating between unity and fragmentation, with elites perpetuating the cycle of manipulation and sabotage. Understanding the true role of SSDF, SNM, USC, and their interactions provides not only a correction of the historical record but also a lens through which to interpret Somalia’s contemporary challenges under federalism.

References

Adam, H. M. (1994). Formation and recognition of new states: Somaliland in contrast to Eritrea. Review of African Political Economy, 21(59), 21–38.

Africa Watch. (1990). Somalia: A government at war with its own people: Testimonies about the killings and the conflict in the north. Human Rights Watch.

Amnesty International. (1990). Somalia: A long-term human rights crisis. London: Amnesty International.

Compagnon, D. (1992). Somali armed movements: The interplay of political entrepreneurship & clan-based factions. African Studies Review, 35(2), 85–108.

Hoehne, M. V. (2015). Between Somaliland and Puntland: Marginalization, militarization and conflicting political visions. Rift Valley Institute.

Human Rights Watch. (1990). Somalia: A government at war with its own people. New York: Human Rights Watch.

Laitin, D., & Samatar, S. (1987). Somalia: Nation in search of a state. Boulder: Westview Press.

Lefebvre, J. A. (1991). The Somali coup d’état of 1978 and the emergence of armed opposition. Journal of Modern African Studies, 29(2), 227–251.

Lewis, I. M. (2002). A modern history of the Somali: Nation and state in the Horn of Africa (4th ed.). Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

Menkhaus, K. (2003). State collapse in Somalia: Second thoughts. Review of African Political Economy, 30(97), 405–422.

Prunier, G. (1995). The Somali civil war. In The Rwanda crisis: History of a genocide (pp. 111–134). New York: Columbia University Press.

Samatar, A. I. (1988). The state and rural transformation in Northern Somalia, 1884–1986. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.