Introduction

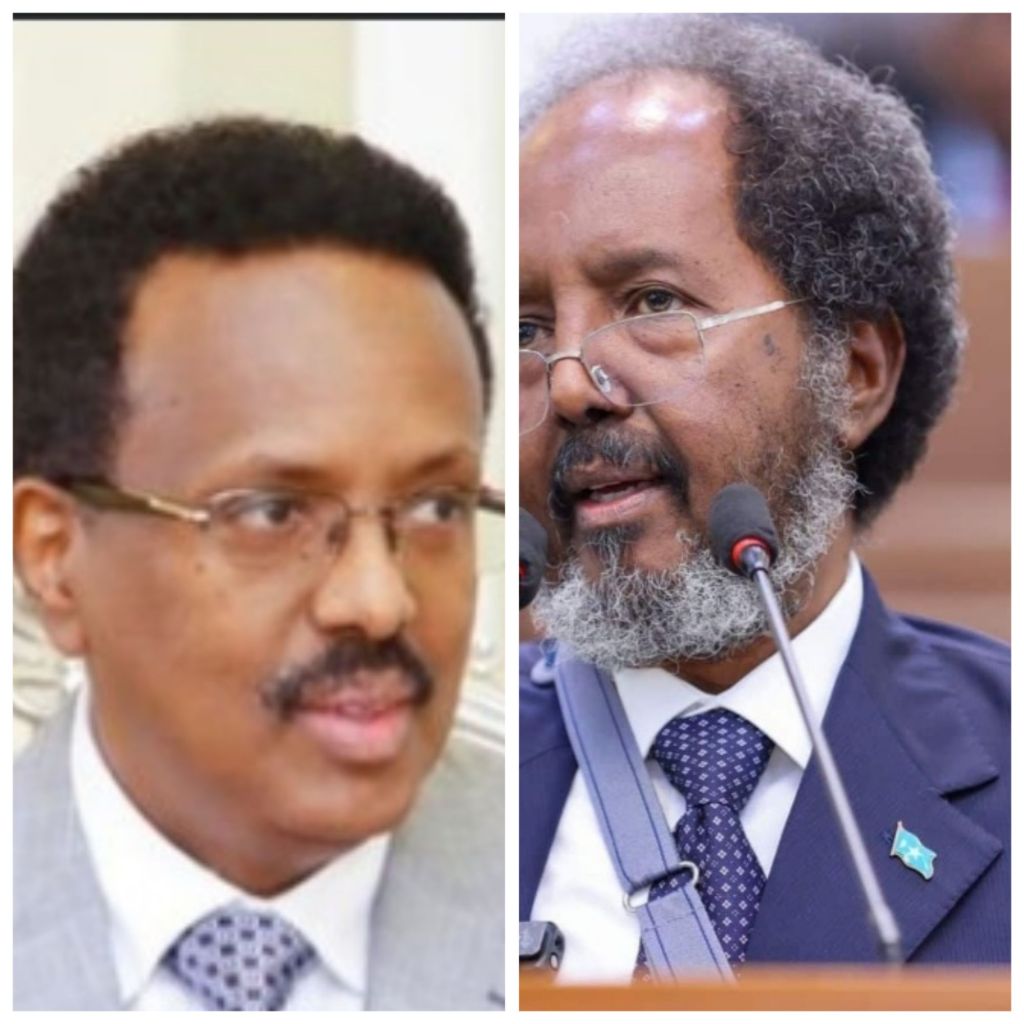

Prime Minister Hamse Abdi Barre’s recent visit to Laascaano has ignited controversy, with critics alleging that its stated objectives—promoting federal unity and recognizing SSC-Khatumo’s administrative status—mask a deeper, more politically charged agenda. Behind the rhetoric of empowerment lies a two-fold mission: advancing President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s contentious electoral reforms and negotiating the release of Somaliland detainees. This essay dissects the alleged deception, urging SSC-Khatumo leaders and residents to scrutinize federal overtures and prioritize regional sovereignty.

Context: SSC-Khatumo’s Precarious Position

The SSC-Khatumo region (encompassing Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn) has long been a flashpoint in Somalia’s complex territorial disputes. While Somaliland claims the area as part of its self-declared independent state, SSC-Khatumo seeks autonomy under Somalia’s federal system. The Federal Government of Somalia (FGS), led by President Mohamud, has intermittently engaged the region, balancing promises of inclusion with strategic political maneuvers. Against this backdrop, Barre’s visit emerges as a critical test of trust.

The Two-Fold Agenda: Beneath the Surface

- Electoral Engineering via NIRA:

The establishment of a National Identification & Registration Agency (NIRA) office in Laascaano, framed as a step toward “one person, one vote” elections, raises red flags. Critics argue that Mohamud’s electoral model risks centralizing power under Mogadishu, using SSC-Khatumo as a testing ground to legitimize federal authority. By positioning the region as a polling station, the FGS may co-opt local governance structures, marginalizing SSC’s autonomy in favour of top-down control. - Prisoner Release: A Bargaining Chip?

Barre’s purported efforts to free Somaliland-linked prisoners in Laascaano suggest backdoor negotiations with Hargeisa. While framed as humanitarian, this move could undermine SSC-Khatumo’s resistance to Somaliland’s territorial claims. Trading detainees for political favors risks normalizing Somaliland’s presence in the region, eroding SSC’s stance against external domination.

The Smokescreen of Federal Recognition

The FGS’s pledge to recognize SSC-Khatumo as a federal administration is lauded as progress. Yet, this gesture lacks substance without enforceable commitments to resource-sharing, security, or self-governance. Historically, Mogadishu’s recognition of regions has often served as a tool to dilute dissent rather than empower. By dangling administrative status, the FGS may seek to co-opt SSC leadership, diverting attention from contentious agendas like electoral reforms and prisoner swaps.

Implications for SSC-Khatumo

The region faces three critical risks:

- Political Exploitation: SSC-Khatumo could become a pawn in federal-Somaliland negotiations, with its sovereignty bargained away for Mogadishu’s interests.

- Erosion of Autonomy: NIRA’s presence might enable federal overreach, supplanting local decision-making with centralized electoral controls.

- Distraction from Priorities: The theatrics of recognition could sideline urgent needs—security, development, and reconciliation—in favor of symbolic federalism.

Conclusion: A Call for SSC-Khatumo’s Vigilance

SSC-Khatumo must approach federal engagements with skepticism. Leaders should demand transparency on NIRA’s role, reject backchannel deals with Somaliland, and insist on binding agreements that guarantee resources and autonomy. Residents must hold both local and federal authorities accountable, resisting hollow symbolism. In a landscape rife with political theatre, SSC-Khatumo’s resilience lies in unity, critical scrutiny, and an unwavering commitment to self-determination. The region’s future must not be scripted by Mogadishu’s deception but shaped by its people’s aspirations.

You must be logged in to post a comment.