Religious leaders across traditions are often expected to serve as moral guides, addressing societal injustices and advocating for ethical governance. In the Muslim world, however, critics have observed a perceived silence from many clergy (ulema) on pressing issues such as corruption, exploitation by foreign powers, and human rights abuses. This essay explores the complex reasons behind this phenomenon, considering historical, political, cultural, and theological factors that shape clerical engagement—or disengagement—with such topics.

1. Political Constraints and Fear of Repression

In many Muslim-majority countries, religious institutions operate under authoritarian regimes that tightly control public discourse. Clergy who criticize corruption or foreign exploitation risk persecution, imprisonment, or loss of patronage. For example, in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, or Pakistan, state-aligned religious bodies often avoid condemning government malpractice to maintain their institutional privileges. Conversely, dissenting voices—such as those of Iran’s reformist clerics during the 2009 Green Movement or Egypt’s Al-Azhar scholars during the 2011 revolution—have faced severe backlash. This climate of fear incentivizes silence, reducing clerical discourse to “safe” topics like ritual observance.

2. Historical Prioritization of Ritual Over Structural Reform

Classical Islamic scholarship emphasized personal piety and legal compliance (fiqh) over systemic critiques of power. While the Quran and Hadith explicitly condemn oppression (zulm), many traditional scholars historically focused on individual morality rather than holding rulers accountable. This legacy persists in conservative seminaries, where curricula prioritize theology and jurisprudence over political philosophy. As a result, some clergy lack the intellectual framework to connect Islamic ethics to modern issues like corporate exploitation or foreign-funded wars.

3. Co-option by Power Structures

Religious institutions in Muslim societies have often been financially and politically dependent on ruling elites. Ottoman caliphs, Mughal emperors, and modern Gulf monarchs have historically patronized clerics to legitimize their rule. Today, this dynamic continues: state-appointed muftis in countries like Malaysia or Morocco rarely challenge policies linked to foreign investors or military alliances. When clergy benefit from these relationships, their critiques of corruption or foreign interference become muted or selective.

4. Sectarian and Identity Politics

In fragmented societies like Iraq or Syria, clergy may prioritize sectarian solidarity over universal moral issues. For instance, during the Syrian civil war, some Sunni clerics framed the conflict as a sectarian battle against Shia-aligned forces, overshadowing critiques of war profiteering or foreign mercenaries. Similarly, in Pakistan, clerical groups often focus on blasphemy laws or Sunni-Shia tensions rather than systemic corruption. This sectarian lens distracts from broader injustices that transcend communal divides.

5. Geopolitical Alignments and Anti-Imperialist Narratives

Some clergy avoid criticizing foreign exploitation because their governments are complicit in it. For example, Gulf states’ alliances with Western powers—often criticized for militarism and resource extraction—are rarely condemned by local religious leaders. Conversely, in anti-Western contexts like Iran, clerical rhetoric may focus overwhelmingly on resisting “Western imperialism” while downplaying domestic corruption or human rights abuses. These narratives serve political agendas but leave systemic issues unaddressed.

6. Institutional Conservatism and Lack of Renewal

Many Islamic seminaries resist modernizing their curricula, leaving clergy ill-equipped to address 21st-century challenges. While the Quranic mandate for hisbah (public accountability) and amr bil ma’ruf (enjoining good) could inspire activism, rigid interpretations of texts often prevail. Additionally, the decline of ijtihad (independent reasoning) in conservative circles stifles innovative responses to issues like migrant labor exploitation in the Gulf or Chinese oppression of Uyghurs.

7. Exceptions and Countercurrents

It is crucial to acknowledge clerics who defy these trends. Figures like Tunisia’s Rached Ghannouchi, Indonesia’s Abdurrahman Wahid, and South Africa’s Farid Esack have blended Islamic ethics with critiques of tyranny and neoliberalism. Grassroots movements, such as Egypt’s pro-democracy clerics during the Arab Spring, also demonstrate the potential for Islamic leadership to confront injustice. However, their marginalization by both states and conservative religious establishments limits their influence.

Conclusion: Toward a Courageous Moral Voice

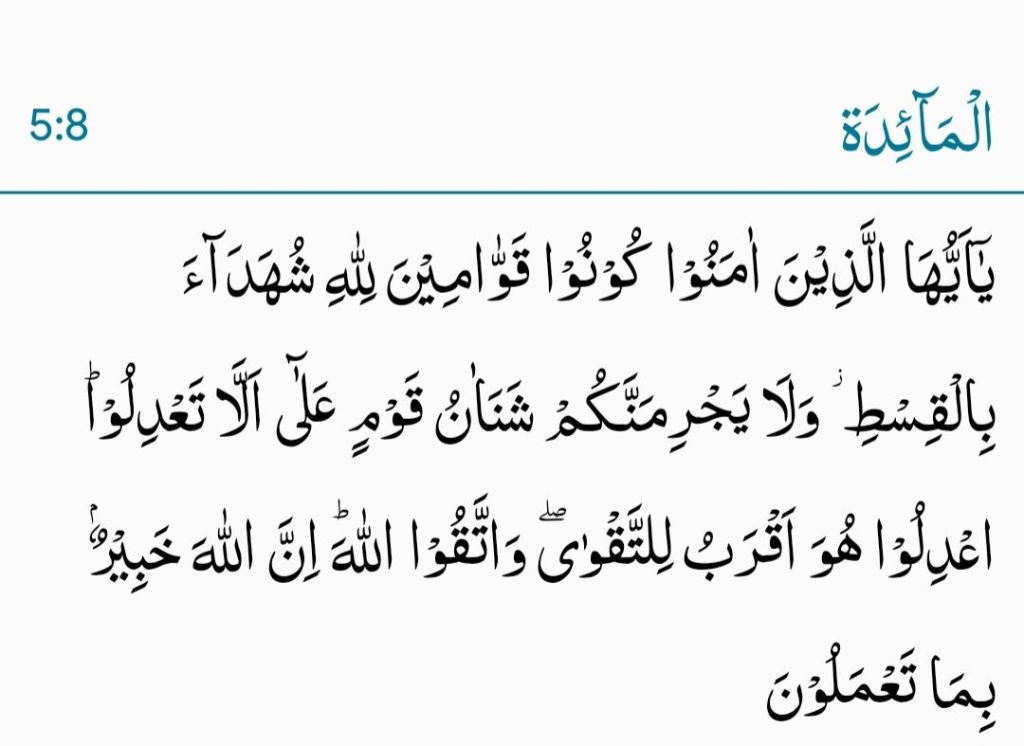

The silence of many Muslim clergy on critical issues stems not from indifference but from complex entanglements with power, tradition, and survival. Breaking this silence requires institutional reforms—such as democratizing religious education, reviving ijtihad, and fostering alliances with civil society—to empower clergy to speak truth to power. As the Quran reminds believers, “Do not let hatred of a people prevent you from being just” (5:8). For the ulema to reclaim their role as moral leaders, they must transcend political expediency and address the urgent struggles of their communities.

“[5.8] O you who believe! Be upright for Allah, bearers of witness with justice, and let not hatred of a people incite you not to act equitably; act equitably, that is nearer to piety, and he careful of (your duty to) Allah; surely Allah is Aware of what you do.”